Dmytro Kuleba became Ukraine’s minister of foreign affairs on March 4, the day after Ukraine’s first confirmed case of coronavirus.

Since then, the ministry with 640 employees in Kyiv, another 2,000 people around the world and a budget of Hr 4.6 billion – or nearly $175 million annually — has been scrambling to help the nation combat the novel coronavirus.

COVID-19 is “the priority that was imposed on me by life,” as Kuleba put it in an interview with the Kyiv Post.

Besides this new challenge, the same old ones – including Russia – remain. The Kremlin is using the global health crisis as the latest pretext to convince Western nations to cancel sanctions imposed for Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014 and its six-year war against Ukraine in the eastern Donbas.

“We have many challenges, starting with taking care of citizens stranded abroad, hunting for aid and supplies for our health care system, and countering Russian attempts to abuse the pandemic for sending around this new narrative that sanctions should be eased or lifted entirely on humanitarian grounds,” Kuleba said. “I know what Russia is doing. There is nothing new in it. The pretext can be different, but the text is always the same: ‘Let’s lift sanctions.’

“For us at Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the pandemic is about more than health,” the minister said. “It is also directly related to combating Russian aggression.”

Youngest of 13 foreign ministers

Kuleba is the youngest of the 13 men who have been Ukraine’s foreign minister. The married father of two children turns 39 on April 19. He joined the ministry in 2003, at the age of 21, and left the civil service in 2013, to the chagrin of his mother, Yevgeniia, who “wanted me to stay. She said I was made for this job. She was right in the end.”

In the last seven years, he briefly served in 2013 as a communications adviser to a deputy prime minister during Prime Minister Mykola Azarov’s government. Amid the EuroMaidan Revolution that ended Viktor Yanukovych’s presidency and the start of Russia’s war in 2014, he served as chairman of the UART Foundation for Cultural Diplomacy.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs pressed him back into service from 2014-2016 to head up strategic communications and did “a pretty good job,” ex-Foreign Minister Pavlo Klimkin said of Kuleba’s performance during those critical years.

Kuleba then became Ukraine’s ambassador to the Council of Europe and, soon after President Volodymyr Zelensky’s election, the deputy prime minister for European and Euro-Atlantic integration.

Throughout his fast rise, he got accustomed to people telling him he’s not old enough.

“Every time I was getting a new job, people were saying he’s too young he’s not going to manage it,” Kuleba said. “It’s a big honor to be foreign minister. But honor also means responsibility. I enjoy what I’m doing because I know what I’m doing and I have the capacity to do that. I will be happy when I will see the results of what I’m doing.”

Crisis as opportunity

Kuleba says he won’t let the COVID-19 crisis overwhelm Ukraine’s foreign policy priorities, including his conviction that the nation needs to have much closer political and economic ties with Asia.

“I see every crisis as not only a source of risk, but also as a source of opportunities,” Kuleba said.

He outlined three of those key priorities:

- Greater emphasis on Asia;

- Securing the positions of Ukrainian exporters in supply chains inevitably reshaped by COVID-19;

- accelerating the digitization of diplomacy.

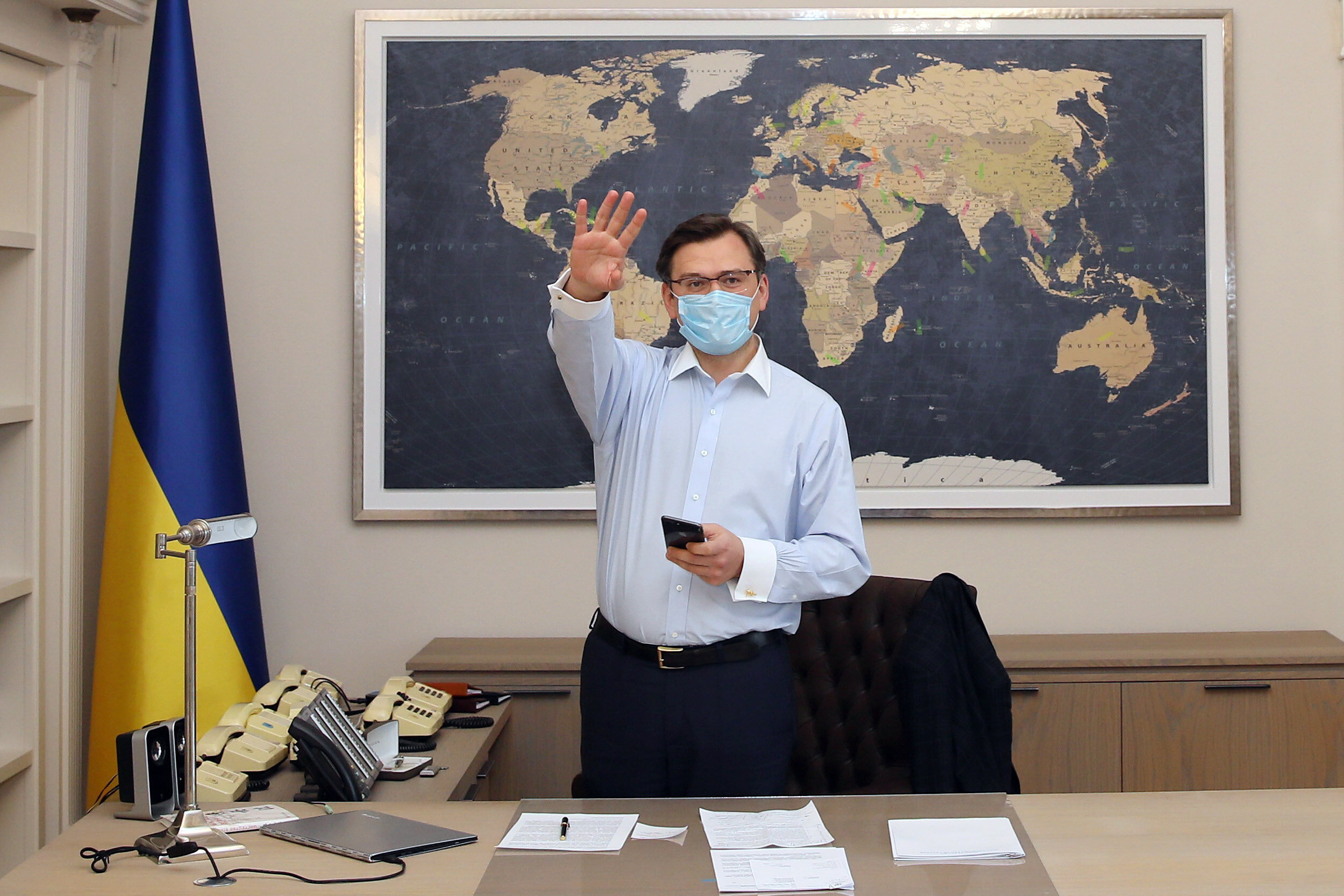

The masks-on interview with the Kyiv Post came on Friday, April 3, the end of the ministry’s proclaimed “Week of Asia.” During the work week, Kuleba spoke with the foreign ministers of China, Indonesia, Singapore, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Tajikistan. In Kyiv, he also met with the ambassadors of India, Japan, and South Korea.

“For many, Asia is mostly about trade. I also see a huge political potential in cooperation with those countries” Kuleba explained. “China became trade partner No. 1 in Ukraine. We have very positive dynamics of trade with India. Our trade with India is very well-balanced; India is looking for opportunities to invest in Ukraine. Why shouldn’t we get deeper relations with them?”

At least one ambassador that he met with, Japan’s Takashi Kurai, was receptive.

“’Week of Asia’” is, as I understand it, based on the idea that the relations with Asia will be paid even more attention in Ukraine’s foreign policy, which I do appreciate, rather than a ‘shift’ to Asia from somewhere else,” Japan’s ambassador told the Kyiv Post. “Whether it is called ‘Week of Asia’ or not, we had a very good meeting the other day with the foreign minister on a number of matters, global, local and bilateral.”

No more grey zone

Kuleba insisted that his greater focus on Asia will not diminish ties with Ukraine’s traditional Western partners – the United States, the European Union, and Canada.

“Politically, I see it this way; traditionally Ukraine is perceived as something in the middle of a triangle, with the United States in one corner, European Union in another, and Russia in a third one. I want this country to break away from this entirely. I want Asia to be heavily present here so that Ukraine is not viewed as something stranded between the West and Russia.

“I have no intention to pay less attention to our relations with the United States, European Union, and Canada. I do have the intention to pay attention that Asia is worth,” he said. “Regrettably, Asia was heavily underestimated.”

He finds support for this approach among at least one foreign policy commentator, Institute of International Relations student Viktor Karvatskyy, identified in an April 8 Atlantic Council op-ed as the CEO of Ukraine’s Adastra foreign policy think tank. “Unfortunately, the Ukrainian Ministry of Foreign Affairs has traditionally had a rather narrow view of the country’s potential strategic partners,” Karvatskyy wrote. “Kyiv has remained largely trapped in a triangular vision of foreign policy revolving around Washington, Brussels, and Moscow. This Soviet legacy has blinded independent Ukraine to the rising geopolitical importance of countries in Asia, Africa, and South America.”

One big sticking point with the Asian emphasis is that, with the exception of G7 democracy Japan, practically all other Asian nations – China, India, and Pakistan among them – do nothing to support Ukraine in its defensive war against Russia’s illegal invasion and annexation. Many of those countries prioritize trade with Russia and don’t support sanctions against the Kremlin.

Kuleba doesn’t see a problem.

“Every country you mentioned respects the territorial integrity and sovereignty of Ukraine. The art of diplomacy is all about navigating through different positions and interests for the benefit of your own country,” Kuleba said. “It will be impossible for me to deal with a country that doesn’t respect the fact of the territorial integrity and sovereignty of Ukraine or that recognizes the illegal annexation of Crimea.”

Reshaped supply chains

The longer the COVID-19 pandemic lasts, the more disruption it will likely cause. That’s why Kuleba said that he is paying close attention to how reshaped supply chains among nations might change – and how Ukrainian exporters can benefit.

It’s too early to know what will be, Kuleba said, but it’s another reason for the Asian shift.

“Asia represents the part of the world where the heart beats, especially the economic heart,” Kuleba said. “It’s obvious that some global supply chains will undergo transformation. The question I’m trying to answer is: How can Ukraine benefit from these changes? How can we ensure the safety of our producers and exporters? Is there a chance to bring more investment from that part of the world?”

Digital diplomacy

The U.S. State Department’s website keeps a running log of all travel by the secretary of state. International travel – summits, bilateral meetings, conferences and other events – traditionally take up a huge block of time for any country’s top diplomat.

While international travel will remain part of the job, Kuleba also thinks that COVID-19 quarantines will accelerate the digitization of diplomacy – particularly through remote meetings held via the internet. He’s already had such a meeting at the German Embassy in Kyiv, when he and German Ambassador to Ukraine Anka Feldhusen had an online meeting with German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas.

“Diplomacy is very conservative by definition. I see COVID-19 as a tool to modernize diplomacy,” he said. “We all live in the 21st century. People have started realizing you don’t have to convene meetings all the time. You can call people. COVID-19 will root those habits into us — video conferences to hold negotiations online, online briefings, e-summits. You can have distance votes in a parliamentary body. There is nothing wrong about it.”

Russian bears down

But, for as long as Russia illegally occupies Ukrainian territory and continues its war, keeping international support for Ukraine’s defense will remain a key task for Ukraine’s foreign minister.

“Ukraine cannot escape geography,” Kuleba said. “Russia will always be on the right side of Ukraine if you look at the map. What we should do instead is we should learn how to take maximum benefit out of our geography and out of our history.”

To some critics, Kuleba’s mere statement of fact sounds too accommodationist.

Suspicions remain about President Volodymyr Zelensky’s administration, whose chief of staff, Andriy Yermak, reignited doubts by publicly flirting with the idea of direct negotiations in a consultative council between Ukrainian officials and Kremlin-backed separatists occupying parts of the far eastern Donbas oblasts of Donetsk and Luhansk.

But Kuleba said there will be no foreign policy change or any diminution of the Foreign Ministry’s role in seeking an end to Russia’s war. “I do not see any indicator of a policy change. It’s absolutely clear that Russia attacked Ukraine, Ukraine is defending itself.”

The ministry takes the lead in the diplomatic exercise known as the Normandy Format, involving representatives of the warring parties in sporadic talks mediated by Germany and France.

Meanwhile, Yermak takes the lead role in contacts with Russian President Vladimir Putin’s current point man on the issue, Dmitry Kozak, and in the Trilateral Contact Group mediated by the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe during many rounds of talks in Minsk, Belarus.

“We have a very advanced institutional framework to deal with the conflict,” Kuleba said. “The only change in the Crimea track which is possible is the de-occupation and withdrawal from Crimea by Russia. There can be no other change in policymaking.”

But he said: “We have to learn how to deal with Russia and look for solutions with them if our goal is to de-occupy our territories — Crimea and the occupied parts of eastern Donbas.” Ukraine must avoid a frozen conflict in Russia’s war, Kuleba said, calling such an outcome “a road to hell.”

As for the future of Ukraine-Russia relations, he said, “let history decide.” But he acknowledged the two countries could go the route of India and Pakistan – in a constant state of warfare and not speaking with each other – or Germany and France – former enemies who are now allies leading the 27-member EU.

“What I know for sure is Russia should withdraw from Ukraine and Ukraine should keep developing as a European democracy with strong ties to Asia.”

Foreign Ministry sidelined?

One of Ukraine’s longest-serving foreign ministers is Klimkin, who held the post for more than five years under President Petro Poroshenko from 2014-2019. He believes that Zelensky has sidelined the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, especially involving “the most important tracks” – Ukraine’s relations with the United States and Russia.

“It’s a shame the Foreign Ministry is not part of the decision-making in foreign policy,” Klimkin told the Kyiv Post. He said he suffered a similar situation under Poroshenko, a former foreign minister, in 2014-2015, but said that by 2016 the ministry was shaping key policies and taking the lead in most areas.

He takes a dim view of Ukraine’s foreign policy today. “We have now no strategy whatsoever,” Klimkin said, calling it an inevitable byproduct of a lack of political will and human capital.

Regarding his successors, he believes that Vadym Prystaiko got switched out in a matter of months by Zelensky because he ran the ministry “in a bureaucratic way,” while Kuleba is an “expert in communications technologies,” which is always in demand on the world stage.

Kuleba dismisses Klimkin’s view as rubbish.

“I remember this narrative of the foreign ministry being sidelined since my first year in the university, which was 1998,” Kuleba said. “Was Klimkin sidelined during his tenure in office?”

Ukrainians stranded abroad

Ukraine gave citizens until March 28 to return to the nation by regularly scheduled commercial flights. Special charter flights were added after that date, reducing the number of Ukrainians stranded abroad and seeking repatriation to an estimated 11,000 people around the world. He launched the “Zakhist” or “Protection” program to help organize and reach out to Ukrainians stranded abroad.

Kuleba said that Ukrainian taxpayers can’t buy these citizens return tickets or pay for their hotel bills, but the Ministry of Foreign Affairs can help them on legal issues, keep them informed and try to find them accommodations until return flights can be arranged. Ukrainians continue to trickle back in, but Kuleba said that “the program of reparations will be resumed pending the capacity of the government to provide observation of the citizens who are coming home,” he said.

Ukrainian Deputy Health Minister Viktor Lyashko told the Kyiv Post on April 8 that the government still strictly requires observation of returning Ukrainians for 14 days “in the special places, not self-isolation.”

Hunting for supplies

The Foreign Ministry is active in trying to secure medical supplies, including critical lung ventilators, with the help of other governments.

“There is a global hunt for these things. Our embassies are looking for suppliers all around the world. Then we help with logistics. Where necessary, we help with diplomatic assistance provided to the cargoes being shipped to Ukraine,” Kuleba said. “We also negotiate with international organizations like the United Nations or the World Health Organization to see what they can help us with and bilaterally with countries.”

The ventilators are in such demand now that one private supplier even reneged on Ukraine’s order for 10 of them, even though payment has been made. Bidding wars are breaking out in the private and public sectors for the equipment needed to keep alive patients who become critically ill with COVID-19.

The best the ministry can do, he said, is to ask governments to put in a word with private suppliers to consider Ukrainian requests “as a priority. It’s something I’m personally doing and something our ambassadors are doing.”

Budget cuts

Ukraine is trying to redirect at least $2.5 billion from the state budget to buy medical equipment and provide financial assistance to citizens suffering because of the economic fallout of COVID-19. The budget cuts suggested for Kuleba’s ministry are necessary and bearable, he said.

“The biggest resource I lack is not even money, it’s people,” he said. “We need more people with fresh ideas, with the ability to deliver.”

But he is trying to convince parliament to keep alive the state-funded Ukrainian Institute, which promotes the nation’s image abroad and counters Russian propaganda and misinformation.

Volodymyr Sheiko, director general of the Ukrainian Institute, said the annual budget had been set at Hr 78 million ($2.8 million), but parliament wants to cut it to Hr 25 million ($900,000). He’s hoping to for a compromise Hr 50 million ($1.8 million).

“We believe that cultural and public diplomacy and building a positive image of Ukraine is part of the national security of Ukraine, one of the key pillars of Ukraine’s foreign policy and it has to be funded properly,” Sheiko told the Kyiv Post.

Relationship with Zelensky

The day before the Kyiv Post’s April 3 interview, Kuleba said he saw Zelensky three times.

“It was not because I was calling, but because his international agenda is full and I am involved in staff meetings related to COVID and other issues,” Kuleba said. “My approach has always been the same: bother your superiors only in those cases where you cannot handle the issue yourself. Do not try to be next to the boss all the time. Do your work and deliver results.”

He said he would resign rather than carry out a foreign policy that he disagreed with. He is not expecting that to happen with this president.

“I understand what his strategy is. I share the principles. I took the job to help him deliver.”

Kyiv Post staff writer Daryna Antoniuk contributed to this story.