NEW YORK — A museum has staged an exhibition chronicling Ukraine’s first struggle in modern times to build a state using artifacts scattered around the globe for a century and putting many on display for the first time.

Called “Full Circle: Ukraine’s Struggle for Independence 100 Years Ago,” it brings to life the tumultuous events between 1917 and 1921 that laid the foundations for Ukrainian statehood.

The exhibition, at the Ukrainian Museum, can be seen until Sept. 29 at 222 East 6th Street in the heart of New York’s “Ukrainian village” area.

The exhibition brings together scores of artifacts, many of them unique. Some had remained hidden in Ukraine or had found their way into the hands of private collectors there. Others had been taken for safekeeping to countries in Europe and North America where Ukrainian exiles, some of whom had taken part in the dramas surrounding the struggle for independence from 1917 to 1921, settled.

The person who led the team putting the exhibition together, Yurii Savchuk, is a senior researcher from the Institute of History at the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine in Kyiv. The exhibition’s layout and design were conceived by Volodymyr Taran.

Savchuk, who studied in Vinnytsia and gained his Ph.D. in Kyiv in 1992, told the Kyiv Post that the circle in the exhibition’s title began in 1917 and closed as the world recognized Ukrainian independence in 1991.

“This is the first time many of the items in the exhibition have ever been seen in public,” he said. “Some have been reunited for the first time since the events that produced them a century ago.”

He said the main organizers of the exhibition were New York’s Ukrainian Museum, the Museum of Kyiv History, and the Sheremetiev Museum, also in Kyiv.

Another 23 museums, archives, libraries, institutions of learning, and private collectors from four countries — Ukraine, the U.S., Switzerland and Bulgaria — also contributed. Many private and institutional sponsors, mostly from the Ukrainian community in the U.S., donated the funds necessary to mount the exhibition.

Nation forged in war

As the events covered by the exhibition begin in 1917, the First World War is still raging with ethnic Ukrainians fighting in the armies of two rival empires, the Austro-Hungarian and the Czarist Russian.

Ethnic Ukrainians, sharing a common culture and language, had long been divided between the two empires. The Austro-Hungarian Empire encompassed most of today’s western Ukraine, while the central and eastern parts of the modern state were located in the Russia Empire.

Millions of disaffected soldiers from the Russian Empire, including hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians, started quitting the front lines, where they faced German and Austrian armies, in 1917, heading home and triggering volcanic political upheavals.

A February 1917 revolution in St. Petersburg ousted the Czar and ushered in a Russian-dominated pseudo-democracy, which was itself ejected later the same year by the communist coup d’etat known as “the October Revolution.”

Ukrainians initially sought to use the 1917 revolutions to gain more autonomy for their people but their efforts were rebuffed. Both anti-communist “White” and Bolshevik “Red” Russian political forces shared a loathing for Ukrainians’ aspirations and made clear they would not countenance Ukrainian independence.

Eventually Ukrainians in the former Russian Empire opted for complete independence and until 1921 were continuously attacked by White and Red armies.

Ethnic Ukrainians in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which was disintegrating after its defeat in November 1918, formed a Western Ukrainian National Republic which immediately plunged into conflict with Poles claiming the same territory for a new state of their own.

The exhibition charts the experience of ethnic Ukrainians in the east and the west. It traces the different types of government that took power in both Ukrainian entities — an autocratic “Hetmanate” followed by a more representative Socialist “Directory” in the east and a parliamentary form in the Western Ukrainian National Republic.

One exhibit, is a faded blue and yellow flag that had been flown during an all-Ukrainian military committee congress in what was still the Russian Empire in January 1917. It was later used by the Ukrainian ambassador to Riga until 1921.

Among the many photographs are some indicating that Ukrainians all over the Russian Empire had a profound sense of their identity as a separate people. Surprising pictures show crowds of ethnic Ukrainian troops from the Russian Czarist Army holding rallies in the Russian cities of St Petersburg (at that time called Petrograd) and Khabarovsk in the spring of 1917.

Dozens of important documents include the peace treaty signed in Brest-Litovsk on Feb. 9, 1918 between the Ukrainian National Republic and the Central Powers — Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, Germany, and Turkey, recognizing Ukraine. Bulgaria, which has one of the only remaining copies, loaned it for the exhibition and it was delivered personally by Mihail Gruev, director of Bulgaria’s State Archives Agency.

Unfortunately for Ukraine, those states were defeated by the end of 1918 by the Western alliance led by Britain, France and the U.S. and they were lukewarm in their support for Ukrainian independence.

Another document displayed is the Jan. 22, 1919 proclamation on the unification of the Ukrainian National Republic and the Western Ukrainian National Republic into a single Ukrainian state with its capital in Kyiv.

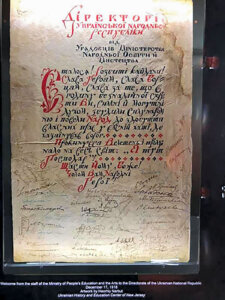

One of the items from the exhibition chronicling Ukraine’s fight for independence in 1917-1921 on display in the Ukrainian Museum in New York. (Courtesy)

Symbols of statehood

Among the scores of other exhibits are the symbols and ephemera of operating a nation: the state seal of the Ukrainian Central Council and the Great Seal of the Ukrainian National Republic; stone printing plates to produce 1918 Ukrainian banknotes; medals and maps.

Savchuk said that many of the artifacts showing that millions of Ukrainians had built and fought for their own modern, democratic state were inconvenient for Moscow and were obliterated or kept hidden by the Kremlin and only unearthed or returned after 1991.

There was little information, he said, that the Ukrainian government had Jewish members and a ministry for Jewish affairs. One of the official seals of the ministry dealing with Jewish affairs is on show and there are banknotes with Ukrainian, Russian and Hebrew scripts.

Another unusual item is a key to Kyiv’s City Hall, which was used as a parliament. It was taken and preserved by Mykola Yarymovych, a lieutenant of the Galician Army during its retreat from the Ukrainian capital on Aug. 31, 1919.

The nation-building efforts were conducted against an unceasing background of war, which eventually doomed that first attempt in the 20th century. That military dimension is reflected in the artifacts on display. There are parts of military uniforms such as epaulettes from various military units, helmets of Austrian and German design, a Ukrainian Navy officer’s hat and Ukrainian air force goggles from 1918.

Some of the items relate to efforts to keep resistance alive after the communists had overwhelmed the nascent Ukrainian state. There are orders from the Ukrainian leader, Symon Petliura, ordering partisan warfare, written on a handkerchief for easier concealment by covert messengers.

There is an official seal used by Nestor Makhno, leader of a Ukrainian anarchist state with an efficient military which wrought devastation on its enemies and long kept Russian communist forces at bay as Ukrainian independence was being crushed elsewhere.

In fittingly irreverent style the anarchist leader’s seal is fashioned out of the cylinder that holds bullets in a revolver.

There is a package of money for a prominent Ukrainian government member, Volodymyr Vynnychenko, sent abroad to try to win international support for Ukraine. Its wax seal bears the Ukrainian state emblem and has never been opened. What sort of currency it contains within has been lost in the mists of time.

Echoes of the past

Some of exhibits testify to efforts by the diaspora to support the embattled Ukrainian republics. There is a letter from the American diaspora to the League of Nations petitioning recognition of the Ukrainian state and the pen used by U. S. President Woodrow Wilson to sign the Ukrainian Day Proclamation in April 1917 — after lobbying by the Ukrainian-American diaspora.

It is easy for visitors to the exhibition to recognize parallels between those first efforts to forge a Ukrainian state and the current bloody conflict against the same enemy, Russia, that used war and terror to suppress Ukraine’s independence bid a century ago.

Apart from the date, a Red Army poster from 1920 explaining why the Soviet regime needed the coal and steel producing Donbas area could just as well have been printed by Moscow’s puppet forces occupying the territory today.

Another chilling item is the first official instruction issued by communist authorities which had just occupied the city of Lutsk. Called “Prykaz #1 Lutsk, Volyn” and dated Aug. 19, 1920, it is an ominous order for all inhabitants to list the books they own.

Savchuk visited Ukrainian museums and institutions in North America and Europe to collect information for the exhibition. Among the treasures he came across were scores of colorful and skillful lithographs depicting the various uniforms of Ukrainian military formations drawn from memory by a former officer, Mykola Bytynsky, in Ukraine’s forces during those turbulent years.

Seldom seen, they had mostly been hidden from view in a Ukrainian museum and library in the American city of Stamford, in the state of Connecticut.

Savchuk said a main purpose of the exhibition was to pay tribute those trying to build Ukraine against overwhelming odds.

But, he said: “The exhibition is not just information, not just paying respect to those involved, but it contains lessons for today. We see historical parallels between now and then, we see that the issues and words from 100 years ago can absolutely be applied today… they are a warning for our contemporaries.”

Savchuk said that a 1915 gramophone recording of the Ukrainian national anthem was played at the exhibition’s April 7 opening.

In that rendition, sung by Ukrainian Americans long passed away, he was astonished to hear a couplet with the words “we will remember hard times and the evil hour of those who courageously died for our Ukraine.”

“Those words aren’t in the version that we sing today but I think, like the events that inspired this exhibition, they are as relevant today as they were then.”