In 2014, a nation energized by revolution and then traumatized by Russia’s military invasion elected Petro Poroshenko by a landslide. Now polls show he is fighting for his political survival on March 31. What went wrong?

He’s a Ukrainian billionaire who promises to swiftly end the war, find ways to work with Russia, defend the Russian language along with Ukrainian, and make “zero tolerance for corruption” Ukraine’s national idea.

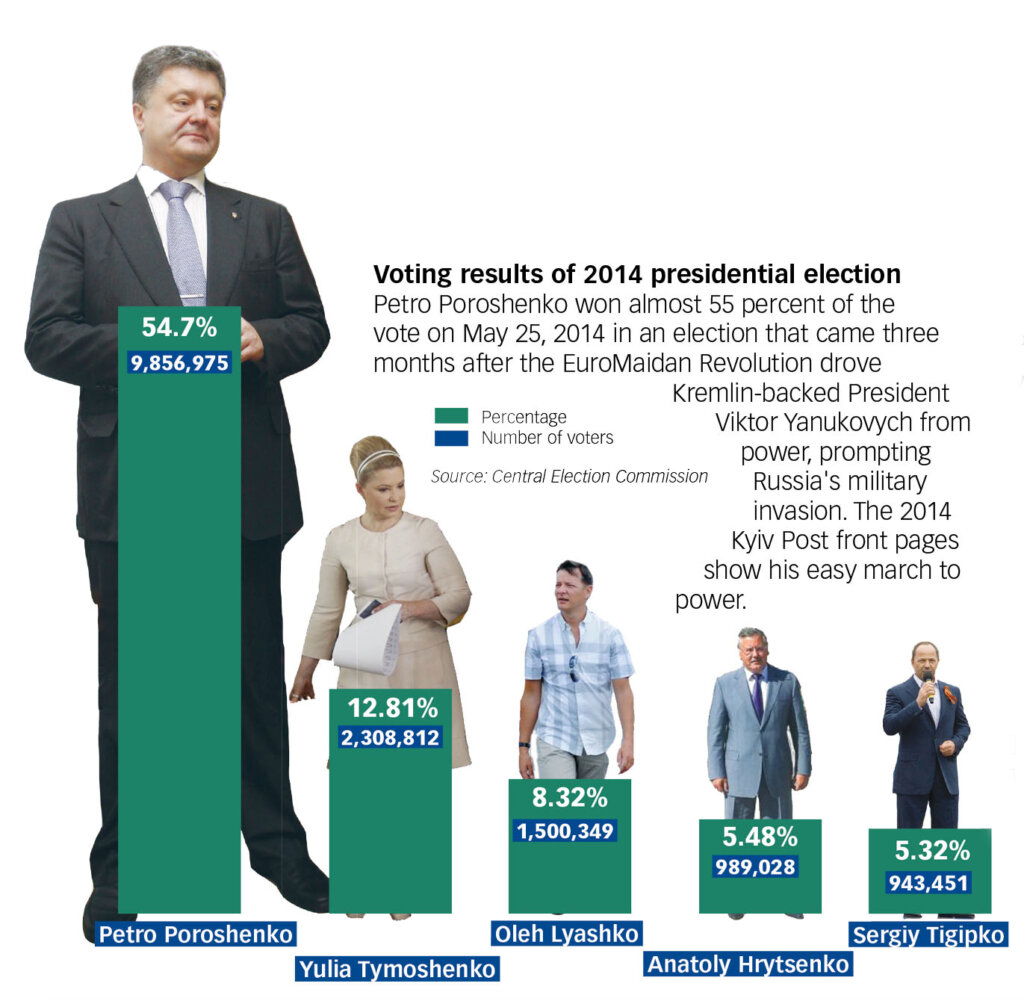

This is Petro Poroshenko in the spring of 2014, during the campaign race for the presidency, which ended with his first-round victory on May 25 with almost 55 percent of the vote.

Five years later, in the spring of 2019, Poroshenko is seeking re-election. The only similarity to his 2014 campaign, however, is that he’s still a billionaire.

Now he speaks less about changes and more about God. He calls Russia the “enemy,” vows to defend the Ukrainian language and build a “great country.”

From a modern “dove of peace,” Poroshenko has morphed into a hawkish conservative nationalist. His election slogan changed from “To live in a new way” in 2014 to “Army, language, faith: We are heading our own way” in 2019.

This rebranding has worked well, helping Poroshenko build up support in the Ukrainian-speaking west and south, political analysts say.

His rating has been steadily rising and he is neck and neck with former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko for second place in the March 31 election. The runner up in the first round wins a place in the April 21 runoff election, likely against political satirist Volodymyr Zelenskiy, who has been leading the race since January.

Poroshenko “has become the main nationalist, pushing the nationalists out of their usual electoral territory,” political consultant Oleksiy Kovzhun told the Kyiv Post.

But if he reaches the second round, Poroshenko’s current patriotic narrative will scare off Russian-speaking voters, risking defeat to a more moderate candidate.

“’Army, language, faith’ will become his big enemy then,” Kovzhun said.

Oleg Medvedev, a spokesman for Poroshenko’s campaign and a speechwriter for him, sees nothing strange in the changes from 2014 to 2019.

“If you noticed, something has happened in the last five years,” he said. “The war happened, Russia attacked Ukraine’s economy, there was a reorientation of the markets, a geopolitical reorientation, the creation of the army, the creation of the church, a new society. People now think in a different way.”

The Kyiv Post requested an interview with Poroshenko multiple times during his five-year reign, but never got it. Instead of giving individual interviews to Ukrainian media, Poroshenko prefers group TV interviews with representatives of the TV stations loyal to him.

An outdoor advertising worker finishes hanging a huge billboard with the face of President Petro Poroshenko on a building in Kyiv’s downtown on March 1. The slogan on the billboard reads: “There are many candidates, but there is only one president.” (Volodymyr Petrov)

Then and now

In 2014, Poroshenko received the majority of the vote in all of Ukraine’s oblasts.

Some residents of the eastern Donetsk Oblast who supported Poroshenko in 2014 told the Kyiv Post that they were hoping that Russian-speaking Poroshenko, who had a confectionery factory in Russia and knew how to negotiate with Russia’s President Vladimir Putin, would quickly stop the war with Russia that started a month-and-a-half before the election. He promised it during his campaign.

Although Poroshenko was 48-years-old and had been a fixture in Ukrainian politics for 16 years when he was elected, he was perceived by many voters as a new face who could rescue the country from crisis and war. He was pro-Western, open to the press, and promising to unite the country.

Poroshenko delivered part of his inauguration speech in June 2014 in Russian, addressing residents of the embattled Donbas. He promised them free use of the Russian language and “not to divide Ukrainians into the right and wrong types.”

“Ukraine is diverse, but it is strong in its spirit and united in its spirit,” he continued in Ukrainian.

Yet in February 2019, Poroshenko’s support in the Ukrainian-speaking west and center of the country was twice as high as in the predominantly Russian-speaking south and east, according to a poll by Rating Sociological Group.

In his annual address to the parliament in September, Poroshenko said: “Army, language and faith is not a slogan. This is the formula of the modern Ukrainian identity.”

As critics blamed Poroshenko for failing to undertake fundamental changes, including establishing rule of law and tackling corruption, he switched to the areas that he sees as his main merits. Poroshenko’s supporters praise him for rebuilding the army, supporting the Ukrainian language, and helping the Ukrainian Orthodox Church gain independence from Moscow.

Political analyst Volodymyr Fesenko said Poroshenko is now promoting “conservative and fundamentalist values.” As a result, Poroshenko’s ratings have doubled in western Ukraine and increased by one-and-a-half times in central Ukraine and in Kyiv since autumn, according to Fesenko.

Real and imaginary

Poroshenko showed a lot of bravery during the 100-day popular uprising known as the EuroMaidan Revolution that prompted his predecessor, Kremlin-backed Viktor Yanukovych, to flee to Russia on Feb. 23, 2014.

His political emergence started when he climbed onto a bulldozer and tried to placate an angry crowd that was storming the Presidential Administration on Dec. 1, 2013. It was one of the most remarkable days of the EuroMaidan Revolution.

Then, in late February 2014, Poroshenko became the only Ukrainian presidential candidate to dare to visit Crimea, when it was already under invasion by Russian soldiers without insignia. In April 2014, he risked a trip to Luhansk when it was controlled by Russian proxies. After his election, he kept a campaign promise to make his first trip to the war-torn Donbas.

But in 2019, Poroshenko travels around Ukraine almost in secret, without prior public announcements of his trips. Surrounded by dozens of bodyguards, he comes to Soviet-style meetings with local officials and local people who are usually bused in specially.

He almost never talks to the press and comes up to people briefly to shake hands and take selfies. If anyone dares to criticize him, Poroshenko often gets angry.

During one of such visits to Zaporizhia in February he grabbed a hat from the head of a woman who had been shouting something at him. His press service later said he did it by accident, although it doesn’t look that way on the video. Later, at the same rally, he tweaked a man’s nose.

“Go to church, light a candle, for you are a non-believer. And the Lord will soothe you,” he said in January to an activist in Cherkasy Oblast who asked Poroshenko when he was going to fight corruption.

In cases like this, Poroshenko “shows his real side behind the presidential gilded facade,” Kovzhun said.

“He believes he’s the best thing that has happened to this country,” Kovzhun added. “But when he sees that his chances are really shaky, he gets angry and irritated with people who don’t appreciate him.”

President Petro Poroshenko poses for a photo with children in Ukrainian national dress in a church in Zhytomyr, where he came on Jan. 17 to display the tomos, a decree granting independence to Ukraine’s Orthodox Church. Poroshenko toured the country with the tomos to boost his popularity. (Oleg Petrasiuk)

Promises forgotten

Just after coming in power in 2014, Poroshenko promised to sell most of his business and fight corruption, following the example of Singapore.

“Start with putting in prison three of your friends,” he told a newly appointed Prosecutor General Vitaliy Yarema in June 2014, quoting the reformist leader of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew.

But in the next five years, neither Yarema’s nor Poroshenko’s friends and nor any top officials have been put in jail.

Poroshenko didn’t sell his main business, Roshen confectionery company, claiming instead that he had handed it over to a Swiss “blind trust” that he would not control. His confectionery factory in Russia stopped working only in 2017.

His own wealth has been increasing in recent years and reached $1.1 billion in 2018, according to the ranking of the richest Ukrainians by Novoye Vremya magazine.

Out of all of the unfulfilled promises, Poroshenko has publicly apologized only for his failure to stop the war. He did so in 2018, four years after being elected.

Nevertheless, during Poroshenko’s presidency, Ukraine has signed a political and trade association agreement with the European Union, its citizens have received visa-free travel to most of Europe, the country has cut its gas dependence on Russia, and the state has moved forward in decentralization and health reforms.

Poroshenko claims credit for all of these achievements.

But decentralization, for instance, is a result of joint efforts by the president, parliament, government and “huge financial and advisory help from the West,” said Valentyna Romanova, local and regional policy expert.

Now Poroshenko promises that, if he is re-elected, Ukraine will apply for EU membership in 2023.

But this promise is also not likely to be fulfilled, said Balaz Jarabik, a nonresident scholar at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

“This does not mean that Ukraine can’t become a member of the EU at some point, but certainly not in this horizon, and not without more structural reforms,” he said.

Copying Russia

Poroshenko’s relationship with Ukraine’s Orthodox church is another testimony to his metamorphosis.

In 2014, he was a parishioner and sponsor of a branch of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church that was subordinate to Moscow.

But in 2018, he spearheaded the process of establishing the Orthodox Church in Ukraine, which has broken free of Poroshenko’s former church. In early 2019, when the presidential campaign officially started, Poroshenko was on billboards all over the country, congratulating Ukrainians on their new church. Next to him on the billboards was Epiphanius, the church’s head.

Read more: “Tomos Tour” shows power of incumbency

The Holy Synod of the Orthodox Church in Ukraine indirectly endorsed Poroshenko for the presidency on March 5, warning that the new president should be a person who “has already shown” he is able to resist Russia’s aggression.

At the forum of his supporters where Poroshenko announced his run for re-election in late January, screens showed Poroshenko standing opposite Putin with the words reading “Either Poroshenko or Putin” — meaning that the victory of any other candidate would be a victory for Russia.

This way Poroshenko’s strategists are trying to create for him the “image of the main patriot, the only one who is able to resist Russian aggression,” Fesenko said.

But because of this trick, Poroshenko’s campaigning style has started resembling that of Putin, Kovzhun said.

“They say if not Poroshenko then who? This is like ‘There’s no Russia without Putin,’ Kovzhun said, referring to a slogan used by Putin’s party in the 2016 parliamentary election in Russia.

Another feature of Poroshenko’s 2019 campaign is the abundance of the “Poroshenko trolls,” people who massively and often aggressively endorse him on social media, a tactic that resembles that of Russia’s paid trolls.

Oleh Medvedev, a spokesman of Poroshenko’s campaign, said Poroshenko has many supporters on the internet and that their behavior is no worse than Poroshenko’s critics.

“Do you think that those who criticize Poroshenko are tender and non-aggressive?” he said.

Slim chances

In May 2014, Poroshenko, the then-presidential candidate, visited the famous Privoz food market in Odesa, a city of 1 million residents located 500 kilometers south of Kyiv. He was accompanied by a local pro-EuroMaidan politician, Eduard Gurwits, who was then campaigning for mayor. He was in the midst of a dense crowd, shaking hands and taking photos.

On March 2, 2019, by contrast, Poroshenko was strolling Odesa’s seafront in the company of Odesa Mayor Hennadiy Trukhanov, who opposed the EuroMaidan Revolution, has been under criminal investigation for embezzlement, held Russian citizenship until 2017 and is criticized for his “mob-rule” style of governing the Black Sea port city.

By allying with the mayors of big cities of eastern and southern Ukraine, Poroshenko is trying to compensate for his low personal rating there, regardless of the fact that their pro-Russian reputation may contradict his nationalistic discourse, Kovzhun explained.

“Walking with Trukhanov, a Russian citizen, it may seem disgraceful from my point of view as a citizen,” he said. “But then I realize that if I had to advise Poroshenko I would tell him to do exactly the same thing.”

But even these efforts may not be enough for Poroshenko.

Fesenko said it will be especially hard for him to defeat Zelenskiy because the majority of Russian-speaking Ukrainians will see Poroshenko as a “representative of the party of war.”

“I don’t know how Poroshenko can win in the second round in a fair way,” Kovzhun said.

Poroshenko’s advisers likely understand this problem, trying to shift his campaign in promoting his fight against poverty, a common problem for the entire country, which is one of the poorest in Europe.

The central and local governments have already started delivering special cash subsidies to people in low-income households, and it has been claimed that Poroshenko’s supporters have benefited from this the most.

Ukraine’s top cop, Interior Minister Arsen Avakov, who reportedly has a conflict with Poroshenko, described in a recent interview with the ICTV television channel a scheme for bribing voters allegedly run by Poroshenko’s campaign workers. He said they had been singling out the president’s supporters in order to pay them for their loyalty — Hr 1,000 ($37) each of special subsidies from local budget funds.

Medvedev, Poroshenko’s campaign spokesman, called the allegations of bribing the voters “groundless.”

Deja vu

On March 13, Poroshenko walked along dozens of people shouting “Shame!” at him in Chernihiv. “See, how they meet the president. Shame on you,” he shouted back at them in irritation.

Poroshenko has come in for massive criticism after the Nashi Groshi investigative project revealed that his long-term ally and business partner Oleg Hladkovskiy and his son Ihor were allegedly for years profiteering on defense sector, which cost state budget millions of dollars losses.

Poroshenko eventually fired Hladkovskiy. But now, instead of stressing his achievements in the development of the army, he has had to answer accusations of robbing it.

And for this he had a tried-and-tested phrase. In an interview to ICTV channel on March 11, Poroshenko promised “zero tolerance for corruption.”

He used exactly the same phrase after casting his ballot on May 25, 2014, the day he was elected president.