Editor’s note: Our 2019 Doing Business in Ukraine magazine is out. Get a PDF version online or pick up a copy in Kyiv.

Ukrainian roads, 170,000 kilometers of arteries connecting cities, towns and villages across the country, are still far from ideal.

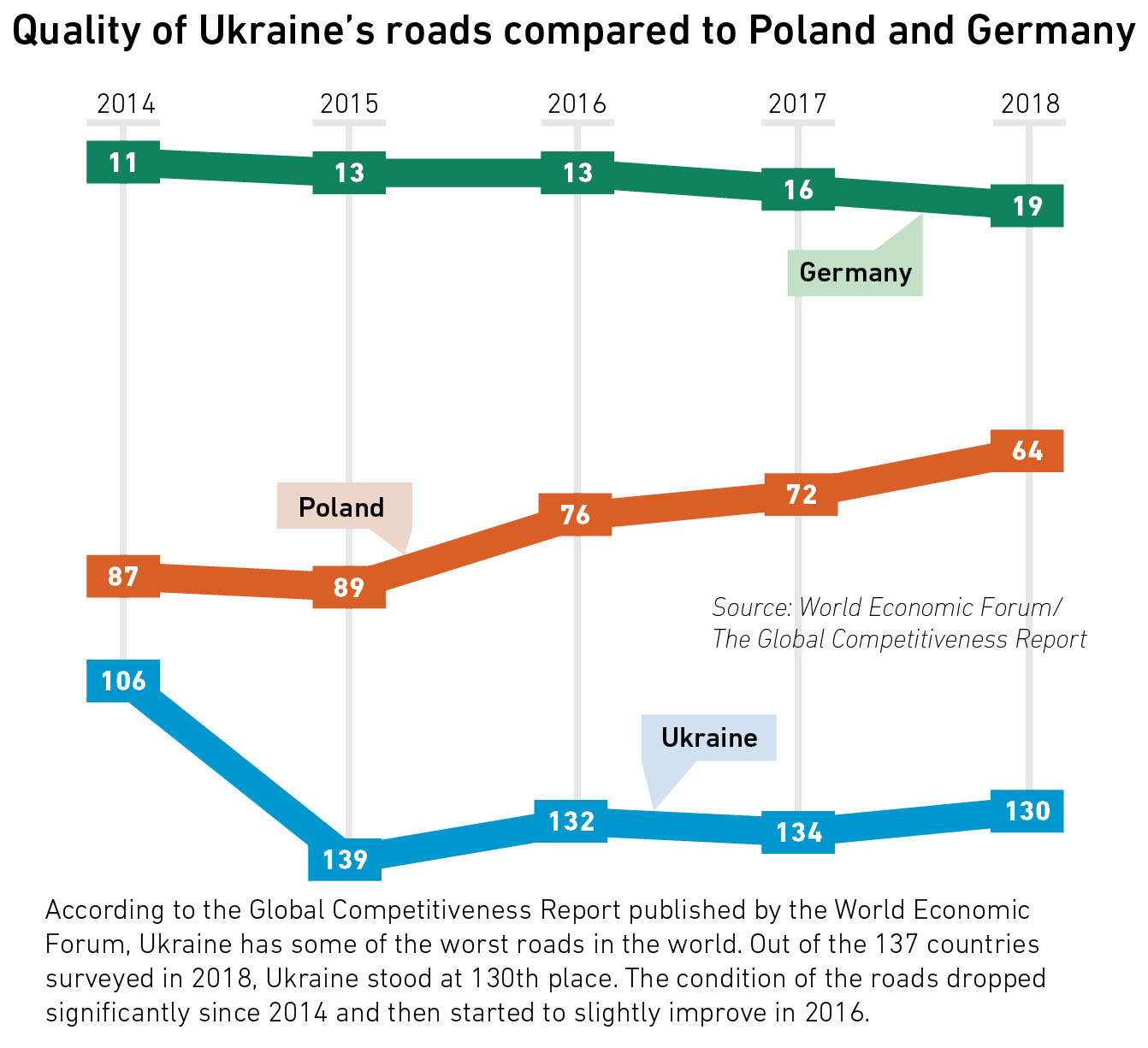

Unlike in neighboring Poland or Belarus, in Ukraine potholes are so common that they can considered distinctive features of the country.

In addition, in Ukraine there are still no toll roads, a weak system of weight control for overloaded trucks and poor enforcement of speed limits. In Poland and Belarus, such problems hardly can be found.

However, there has been some progress in road repairs in the past two and a half years, when Slawomir Nowak, the former minister of transport, construction and maritime economy of Poland, was appointed as the new head of the State Agency for Automobile Roads of Ukraine, better known simply as Ukravtodor.

When he took the job in late 2016, Nowak didn’t realize the scale of work required.

“I didn’t know the real picture. I received an independent report on Ukrainian roads made by the World Bank and it said that 95 percent of them were in critical condition,” Nowak told the Kyiv Post. “But the critical condition of the roads in Europe is when the road requires routine repair. Here it turned out that critical condition is understood in a completely different way.”

In some places, the roads were so bad that motorists found it easier to drive through fields than on the actual roads.

So far, 6,800 kilometers of Ukrainian roads have been repaired, according to Prime Minister Volodymyr Groysman in April 17.

But 90 percent of roads remain in critical condition, Nowak said.

“In Ukraine, for 20 years we did not invest anything. The system has reached almost complete destruction. In fact, we need to rebuild the entire road infrastructure again,” said Serhiy Vovk, director of the Center for Transport Strategies consulting center. “We simply used the legacy that we inherited (from the Soviet Union).”

According to Nowak, the last repair of the road between Mykolaiv and Kropyvnytsky, the administrative center of Kirovohrad Oblast, was in the 1970s.

“There are some roads that have not been repaired since the beginning of construction in the 1950s,” he said.

While Ukrainian roads have gradually been destroyed, Poland and Belarus were systematically repairing their roads.

The first toll highway in Belarus from Brest to Russia appeared more than 10 years ago. In Poland, there is a diverse toll roads system called viaTOLL, which was launched in 2011. By the end of 2018, the Polish treasury received 23.6 billion Polish zloty, or $6.2 billion, through this system, according to the Polish General Directorate for National Roads and Motorways.

In Ukraine, there are currently no toll roads.

Another hot issue for Ukraine, a country with a giant agricultural industry that requires good transport infrastructure, is the lack of durable cement roads. They are especially necessary for heavy trucks in the southern regions of Odesa, Mykolaiv, and Kherson oblasts, where the main gates of Ukrainian export — seaports — are located.

This year, for the first time in 28 years, a tiny part of a cement road under construction in Poltava Oblast opened. So far, travel is allowed on 1.7 kilometers of the road, which begins in the village of Reshetilovka in Poltava Oblast and will connect to the city of Dnipro, a distance of roughly 160 kilometers.

By comparison, a cement ring road with a total length of 160 kilometers was built around Minsk in just two years and was launched at the end of 2016, so that trucks can bypass the capital, something that Kyiv can only dream of.

According to Anton Usov, the European Bank of Reconstruction and Development’s senior adviser on foreign affairs, Belarusian roads can easily be compared to German ones.

Potholes are a regular characteristic of Ukrainian roads. The country’s roads have been mistreated, underfinanced and neglected for decades, making them some of the worst in the world. But Ukraine’s state road agency, Ukravtodor, is looking for ways to fix the problem. (Oleg Petrasiuk)

Poor financing

The huge difference between Ukraine and neighboring Poland is the amount of money allocated to build and repair roads, as well as the way the financing is organized.

In the European Union, there is internal financial support for member states with underdeveloped infrastructure.

“Other richer countries, like Germany or France, give their money so that Poland, Slovakia and Romania (can) align their standard of living with the help of the EU,” said Nowak.

And Poland received a lot. For the period from 2007 to 2015, around $29 billion was allocated for new construction and for national highways alone — roughly 19,000 kilometers.

Ukraine, which is not a European Union member, has no such help.

For the past five years, the Ukrainian government has allocated only $6 billion not only for 50,000 kilometers of national highways, but also for all road infrastructure, according to Ukravtodor.

“We need more funding. It is not enough to repair the main transport corridors at a sufficient pace,” said Nowak.

The sum would be even smaller if the State Road Fund hadn’t been established in 2018. It is one of the most important reforms, Nowak says.

“Every citizen who pumps a car at a gas station pays a fee. Part of the money of the excise tax goes to the Road Fund,” he said. It helped to allocate $1.5 billion to roads in 2018, with $1.9 billion expected this year.

“There is a reason for cautious optimism in the road sector, since we have a Road Fund for two years already. It is a guaranteed source of funds for road repairs,” said the Center for Transport Strategies’ Vovk.

In Poland, there is a National Roads Fund, which covers expenditures for the construction of national roads that connect cities and regions. It uses financial resources coming from the fuel fee, EU funds, bank loans and revenues from toll collection.

Weigh stations, parking lots

Huge potholes, the bane of Ukrainian drivers’ exitence, don’t simply appear out of the blue. They are caused by overloaded trucks.

In the EU, this problem was solved thanks to the “weigh in motion” system, in which road sensors detect weight and photograph overloaded trucks, sending the evidence immediately to the police for investigation. The penalty is calculated automatically to eliminate bribes.

“In Poland, we quickly managed to minimize the number of overloaded trucks, and here it is a terrible problem,” said Nowak.

A pilot project for such a system is currently under construction in Kyiv.

“We are building six gates at the entrance to Kyiv. By the end of the summer, all six must be completed,” said Nowak.

Next year, Ukraine plans to have 50 such points along all the main transport corridors, especially at the entrances to cities and seaports.

However, Vovk believes that, even though this system will quickly pay for itself through fines, there is strong resistancce in Ukraine to moving this facet of law enforcement out of the shadows.

“Illegal transport companies carry 60 or even more tons, instead of the 40 tons allowed, thereby destroying roads. Behind illegal carriers there are often illegal controllers that have certain connections also with the Ukrainian authorities,” said Vovk.

“This is a whole industry,” he added.

Another huge difference between EU countries and Ukraine is the lack of parking places, especially in big cities.

Kyiv recently was ranked 13th among the 403 most traffic congested cities around the world, according to the TomTom Traffic Index report.

It means that drivers spend 46 percent extra travel time to get to their destination in Ukraine’s capital.

“This is a very serious problem for Kyiv Mayor Vitali Klitschko. Everyone leaves their cars where they want. This should be strictly regulated, otherwise there will always be a problem — when, for example, we have five lanes to move (but) two are excluded because cars block (them),” said Nowak.

One of the ways to get rid of this problem is to build Park and Ride places at the entrance to the city, like in Berlin, Paris or Warsaw. People can leave their cars there and continue to travel by public transport.

Additionally, Ukraine will start installing cameras to catch speeders in 2019.

“It’s not that much, but we need to take the first step at least,” said Nowak.