WASHINGTON — As a Russian-engineered war engulfed their country in 2014, two young Ukrainian professionals working in America agonized over how best to help their beleaguered homeland.

During the 100-day EuroMaidan Revolution that ousted Ukraine’s Kremlin-backed President Viktor Yanukovych on Feb. 22, 2014, they had met during protests in the American capital to support demonstrators in Ukraine.

Yanukovych’s government fell apart after he and his cronies fled to Russia. But the two friends, Vitaliy Dubil and Pavlo Fedorenko, watched the grim news showing Russian regular troops and the Kremlin’s puppet forces invading and then waging war on Ukraine.

Dubil and Fedorenko both hail from southeastern Ukrainian cities — Dubil from Dnipro and Fedorenko from Zaporizhya. They learned from relatives about the lack of medical equipment and supplies to help badly-wounded fighters and other victims of the war.

Dnipro and Kharkiv, close to the fighting in eastern Ukraine, had become the main medical hubs for treating the victims from the war zone. But they were not ready for such high numbers of serious casualties and many patients died because of a shortage of surgery equipment and other supplies.

Dubil said: “Our biggest motivation to work on this project was the realization that guys our age and much younger went to the front lines to defend Ukraine’s independence and were returning without some of their limbs and with other terrible wounds. Pasha and I concluded that providing medical equipment and health care services would be the most valuable way of helping our home country.”

Dubil and Fedorenko called their project “Support Hospitals in Ukraine,” a name that succinctly describes its goals.

Dubil, who studied finance and economics in Dnipro Finance Academy, business at the University of Texas and for six years has worked at the International Finance Corporation in Washington, said the two first had to figure out how to turn their “passion to work for fellow compatriots in Ukraine” into a practical plan.

He said: “When we started working on this project we had no experience of health care; shipping large cargoes overseas from the United States to Ukraine; connections with suppliers or authorities or customs in Ukraine. We had no money – only a desire to help our beloved Ukraine.”

They first concentrated on making contact with people they hoped could help out. The breakthrough came when they met Jeannie Martin, an experienced American volunteer from Texas who had worked with charities providing healthcare equipment to poorer countries.

She had connections with an American charity called “Project CURE,” the world’s largest distributor of donated medical relief.

It collects used medical equipment and other supplies that are being discarded by American hospitals and healthcare outfits but are still in good working order and provide years of service to the more than 130 countries Project CURE ships them to.

Dubil explained that in the U.S. new medical equipment replaces older technology in hospitals frequently whereas in Ukraine equipment often remains for decades, with Soviet-era technology still widely used. What, after only a few years, is considered “old” in America is eagerly received by Ukrainian hospitals and doctors.

First shipment paid with their own money

Project CURE would supply the donated medical equipment but Support Hospitals in Ukraine had to raise funds for all the coordinating work and transportation costs to deliver it to Ukraine.

Dubil said they reached out to the Ukrainian community in the U.S. for funds. “But we had to show that we could be trusted, “ he said, “And the cost of the first shipment was covered out of our own pockets and with support from our families and close friends.”

That first container of medical equipment was delivered to two large hospitals in Dnipro in December 2014.

The successful delivery prompted many “crowdfunding” type small contributions of $50 or $100 to the organization as well as larger donations from Ukrainian nongovernmental organizations in the U.S.

Those include two groups formed by the “new wave” of Ukrainian emigrants to America such as “Razom” and “United Help Ukraine,” which have organized demonstrations and other actions to publicize Russia’s war on Ukraine and collected funds to help the country of their birth. Older organizations, such as the Ukrainian National Women’s League of America, have also helped generously.

Canadian diaspora organizations have also stepped up. The League of Ukrainian Canadians and Friends of Ukraine Defense Forces Funds donated generously.

Dubil told the Kyiv Post that every item packed in containers is earmarked in advance for a particular recipient.

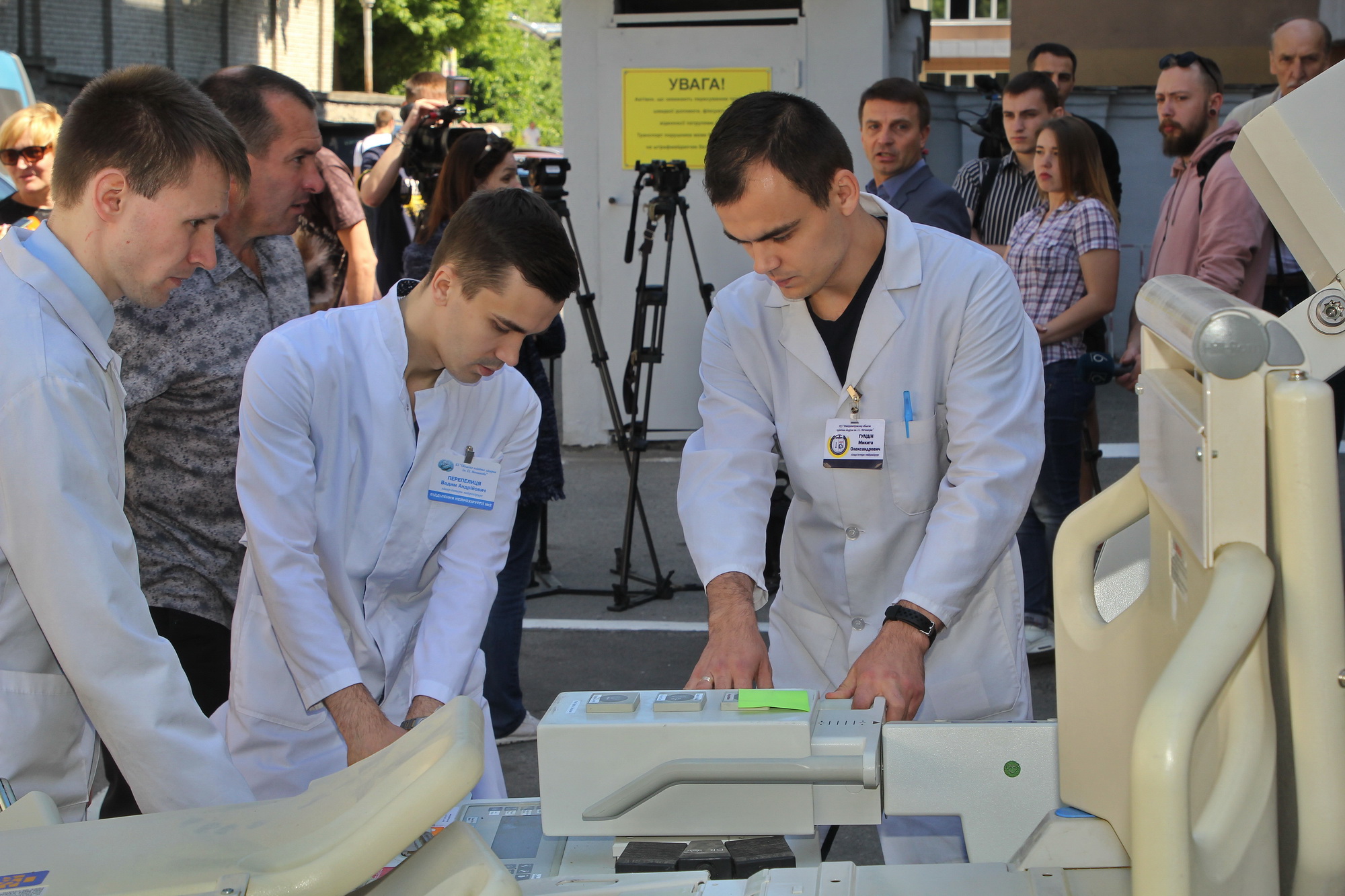

He said that Support Hospitals in Ukraine conducts assessments at hospitals asking for items to check they have the appropriate infrastructure to be able to use what they have requested. They also ensure the recipients know how to operate the items.

“Preparing for each new shipment we go through several levels of assessments and consultations with the main goal to be sure we deliver exactly what each hospital requires.”

All involved are volunteers who work with volunteers in Ukraine to deliver the supplies.

“All the money we receive from donors goes for the operational expenses of our supplier and the operational expenses of transport from the U.S. to Ukraine. We don’t have offices, licenses, staff or any administrative costs. So we are 100 percent efficient in our work,” he said.

So far, Support Hospitals in Ukraine has sent shipments valued at $2.5 million.

He manages the project, focusing on business development, fundraising and maintaining relations with all those involved. Martin is responsible for on-site assessments in Ukraine and Serge Sementsov joined to evaluate SHU’s social impact. Fedorenko still advises but is not as closely involved as before.

The modern technology delivered includes ultrasound scanners, various medical monitors, specialized intensive care unit beds, and a range of surgery, including neurosurgery, equipment.

Project CURE checks that all the equipment works, even supplying transformers to adapt them from American voltages to European requirements and it helps with paperwork such as for customs. The Ukrainian Embassy in Washington has also provided valuable help to navigate the bureaucracy, said Dubil.

In Ukraine, the volunteers partner with an NGO called New Life and a charitable fund called Health Care Support to help with customs clearance and deliveries.

Initially Support Hospitals in Ukraine received some 55 percent of its funds from crowdfunding small donations and 45 percent from partners like the NGOs.

New strategy

As the fighting in Ukraine faded from the headlines (although it has never subsided and claims many dead and wounded each week), Dubil said the number of small donors waned and the project now mainly relies on activist and diaspora groups and NGOs for funds.

Dubil divides the work into two phases. The first phase covers 2014-18 when its shipments supported some seven hospitals. The second phase, he said, will cover 2018-22 and supply another 13 hospitals.

He said that when the project began it was focused on hospitals healing wounded soldiers, including rehabilitation treatment. However, he added: “From 2018, our strategy changed from only military-oriented medical institutions because we hoped the war would end.”

So although still working with military hospitals such as at Irpin near Kyiv, they also responded to requests from health care centers caring for non-military patients receiving neuro-surgery, pediatric surgery, or oncological procedures.

They also worked with regions further from the fighting such as Lviv, Zhytomyr, Cherkassy and Odesa.

For instance the Women’s League provided funds for equipment for two children’s hospitals in Lviv and Zhytomyr.

That was packed into two 12-meter containers in Denver, Colorado, where Project CURE’s largest warehouse is located, in June and is scheduled to reach Kyiv in late August.

Dubil devotes all his spare time to the project and said he hopes a day will come when there will be no more need for these donations. He thinks Ukrainian health institutions are becoming better. But for now, requests are increasing for Support Hospitals in Ukraine’s help as its reputation spreads.

He said: “I call this project my second life because it takes so much of my free time. But there is no excuse for stopping especially as now, after five years, we have acquired so much experience and visibility and know how to work well. In some ways it would be almost a crime not to carry on while Ukraine is going through these big challenges and our support is needed more than ever.”