When the World Cup 2018 football championship started in Russia on June 14, Russia’s now-famous political prisoner Oleg Sentsov was 32 days into his hunger strike.

Sentsov, the 41-year-old Ukrainian film director and writer, is a political prisoner, sentenced to 20 years in prison in a sham trial, allegedly for terrorism. His real crime: Opposing Russia’s invasion and annexation of Crimea in 2014.

Sentsov is determined to draw attention to dozens of Ukrainians, perhaps 71 by the latest best estimate, illegally imprisoned Russia and Russian-annexed Crimea.

The fear is that his convictions and his principles may cost him his life.

Sentsov only drinks boiled water. To keep him alive, prison doctors started intravenously giving him a glucose solution, which should support the functioning of his internal organs and extend his life for a few weeks. They also moved him to a prison ward to monitor his condition. After the 30th day of a hunger strike, the body suffers irreversible effects.

But Askold Kurov, a Russian filmmaker who visited Sentsov on June 4, told the Kyiv Post that Sentsov “was very determined to go by the end.”

As the world’s eyes are turned to Russia for the World Cup, Sentsov’s strike has drawn more attention to the plight of Ukrainian prisoners in the last month than in the last four years.

“This topic was absolutely unnoticed,” said Mariya Tomak, coordinator of Media Initiative for Human Rights.

There are also some hopes that Russian President Vladimir Putin, if he cares about improving his image, might find this a good time to free the prisoners. He did so before Russia hosted the Olympic games in Sochi in 2014.

“Sentsov’s actions are the extreme way of a peaceful struggle,” said Emil Kurbedinov, a lawyer who is defending several Crimean Tatar political prisoners. “And it gives hope to many.”

Worldwide campaign

President Petro Poroshenko on June 8 met for the first time with family members of Sentsov and other Ukrainians jailed in Russia and Crimea.

On the next day, Poroshenko spoke by phone with Putin. They agreed that Ukrainian ombudswoman Lyudmyla Denisova would visit Ukrainians kept in Russia and Crimea, while Russian ombudswoman Tatyana Moskalkova would meet with Russian nationals kept in Ukrainian jails.

Putin had previously refused even comment on Sentsov’s case, repeatedly calling him a “terrorist.” But in late May Putin had to answer questions about Sentsov in talks with French President Emmanuel Macron. On June 8, European Council President Donald Tusk called on the countries of G7 to demand the release of Sentsov.

An international campaign to free Sentsov reached even Russian state TV, where several filmmakers spoke in his support during the award ceremony of Kinotavr, Russia’s largest film festival, which was broadcast live on June 11.

Possible exchange

Lawmaker Iryna Gerashchenko, who represents Ukraine at the peace talks in Minsk, Belarus, said on June 4 in parliament that Ukraine is ready to release 23 Russian nationals convicted in Ukraine in exchange for Sentsov, Oleksandr Kolchenko, who was sentenced for 10 years in the same case, as well as Stanislav Klykh and Pavlo Hryb.

Historian and journalist Klykh, sentenced to 20 years in prison for allegedly fighting in first Chechen war in Russia, has serious mental problems which he acquired after torture by Russian law enforcement.

University student Hryb, 19, was abducted from Belarus by the Federal Security Service, the Russian successor to the Soviet KGB. He was accused of terrorist activity and faces up to 10 years in prison. He is suffering health problems. “Pavlo needs a special medical regime and a special diet, which he can’t get in prison,” his father Igor Hryb said.

Apart from Sentsov, there are at least two other Ukrainian prisoners who currently remain on hunger strike, Tomak said. They are Volodymyr Balukh, a pro-Ukrainian activist, convicted in Crimea and sentenced to for 3 years and 7 months and Oleksandr Shumkov, who was convicted in Russia for involvement with the Right Sector, a nationalist Ukrainian organization.

Gerashchenko didn’t name the 23 Russians kept in Ukrainian prisons. The only name known definitively is Kyrylo Vyshynsky, who worked at the Kyiv office of the Russian propagandist RIA-Novosti news agency. He was arrested by the Security Service of Ukraine, or SBU, on May 15. Ukraine’s prosecutors accuse Vyshynsky, who has both Ukrainian and Russian citizenship, of state treason for work for Russian state propaganda.

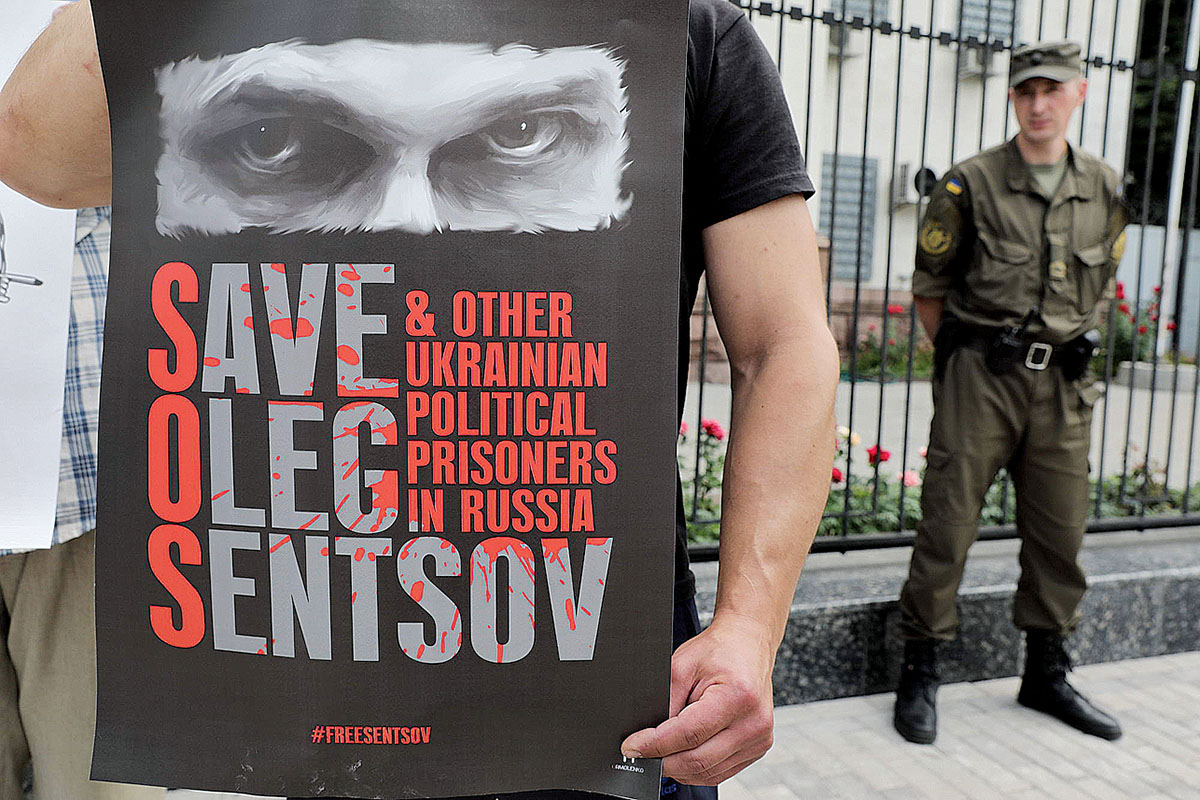

A protester holds a poster in solidarity with Ukrainian filmmaker Oleg Sentsov outside the Russian Embassy in Kyiv on June 13. Sentsov, who is imprisoned in northern Russia on trumped up terrorism charges, has been on a hunger strike demanding the release of all Ukrainian political prisoners since May 14. (Volodymyr Petrov)

More Kremlin prisoners

The number of Ukrainian prisoners is growing every year. Two Crimean Tatar activists were arrested in Bakhchisaray on May 21: Server Mustafayev, who coordinated Crimean Solidarity, the Crimean Tatar civil movement formed in 2016 to support political prisoners and those families, and Edem Smailov, who is a religious leader of a Crimean Tatar community in Bakhchisaray.

They were accused of links to Hizb ut-Tahrir, a pan-Islamist movement banned in Russia, based on secret FSB recordings in a mosque.

“Now they face up to 15 years in jail, which is more than for a murder,” said Kurbedinov, a Crimean Tatar lawyer and member of Crimean Solidarity.

The criminalizing of political movements, like Hizb ut-Tahrir or Right Sector, is a common strategy used by Russian law enforcement to persecute the activists or simply to create the image of fighting against terrorism, Tomak said.

“A person may be sentenced for terrorism even if he has never committed or even planned any violent actions,” Tomak said, adding that 45 out of 71 Ukrainian political prisoners are held under this pretext.

Hope for freedom

Putin has released only nine Ukrainian political prisoners since Russia launched its war against Ukraine in 2014.

The Ukrainian government secured the freedom of Nadiya Savchenko, Hennadiy Afanasiyev and Yuriy Soloshenko. Turkey intervened to secure the releae of Crimean Tatars Akhtem Chiygoz and Ilmi Umerov. Yuriy Yatsenko was released from Russian prison thanks to the efforts of his lawyer.

Yuriy Ilchenko managed to escape home arrest in Crimea and reach mainland Ukraine. Khaiser Dzhemilev, the son of Crimean Tatar leader Mustafa Dzhemilev, and Redvan Suleimanov were released after serving their prison terms.

However the Sentsov saga turns out, he is already providing powerful inspiration and hope to families of Ukrainian political prisoners.

One of them is Yevhen Panov, a former volunteer fighter in eastern Ukraine who was captured while entering Crimea. He was there to help evacuate one family to the mainland.

FSB officers tortured Panov for four days and charges him with planning terrorist attacks in Crimea. Panov is jailed in Simferopol and faces up to 20 years in prison.

Panov’s brother Igor Kotelianets believes the Russian FSB made up the case.

“We will do all possible to make him free through the prisoner exchange,” he said.