Ukraine suffered the worst of the 20th century: Bolshevik Revolution and Russian civil war, the Holodomor, the Holocaust, Nazi and Soviet conquest, Joseph Stalin and many other tragedies.

But not only does the nation endure in the 21st century, many Ukrainians — and their supporters abroad — are working hard to make the country thrive.

Few historians know Ukraine’s past and present better than Timothy Snyder, the Yale University professor, author of “Bloodlands” and frequent visitor to the nation. Snyder has been in Ukraine for the week-long series of events to commemorate the 75th anniversary of Babyn Yar, the ravine in Kyiv where Nazi German soldiers murdered 100,000 people — mostly Jews — from 1941-1943.

Snyder, in an interview with the Kyiv Post on Sept. 29, said he can see three “broad connections” between Ukraine’s past traumas and its present challenges.

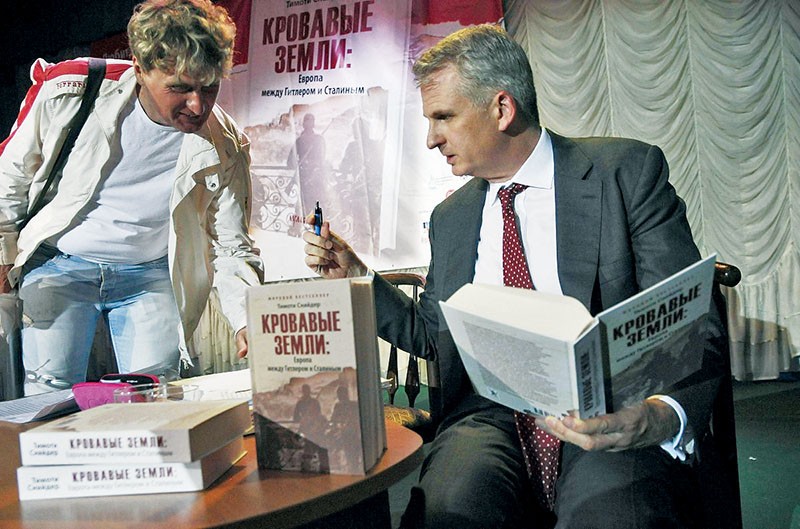

American historian Timothy Snyder of Yale University presents the Russian edition of his book “Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin” on June 22, 2015 in Kyiv. (UNIAN) (source)

Civil society

One is the destruction of civil society during Stalin’s first five-year plan from 1928-1932, when the forced starvation of up to seven million Ukrainians took place ending in 1933. The Soviet idea was to weaken rural life, one of the bedrock strengths of Ukrainian culture.

“The famine destroyed that,” Snyder said. “It didn’t just kill people, it ripped apart relationships, it destroyed people’s trust in one another. I think the ability of people to trust neighbors was seriously deformed by that — the sense of culture coming from the countryside.”

But people’s trust in each other and the strength of civil society have roared back to life, with three progressively stronger revolutions starting just before Ukrainian independence — the Granite Revolution in 1990, the Orange Revolution in 2004 and the EuroMaidan Revolution of 2013-14.

“Absolutely – Maidan, Maidan, Maidan. Each Maidan is more of a success in trust in strangers. Civil society is very functional here. Everyone is struck that you can run a more-or-less modern society during a war with a very weak state and a functional civil society.”

Even the defense against Russia’s war, Snyder said, has depended on civil society. “That requires trust” among people, he said.

Moreover, he said, Ukraine differs from Russia profoundly in “attitude towards the state,” especially the “notion that you have a right to rebel against the state,” which Ukrainians believe far more strongly than Russians. The two nations are “mainly different because of political styles that have emerged over 25 years,” he said.

In fact, one of the reasons for Russia’s war against Ukraine is that, for the Kremlin, “the idea of Ukraine as a European model and a European success is a threat to the way they’ve decided to set up their system…If Ukraine were Belarus, there wouldn’t be a war.”

A woman walks past an exhibition of photographs by Luigi Toscano at the Babyn Yar memorial complex on Sept. 29. The portraits are of people who survived the Holocaust. (Kostyantyn Chernichkin) (Volodymyr Petrov)

Repairing trust in state

The second connection between past traumas and present realities involves people’s trust in state.

That still hasn’t happened yet. And it’s understandable, given the horrible repression that Ukrainians have suffered historically from all-powerful and ruthless rulers.

But trust in the state must return for Ukraine to have functioning government and institutions, Snyder said.

A return to government repression is “not impossible, but it’s unlikely,” Snyder said. “The tipping point was February 2014. The state tried to make people afraid (with the murders of 100 EuroMaidan Revolution demonstrators.) They succeeded. They were afraid. But they acted anyway. It’s hard to go back after the state was beaten.”

Now, Snyder said “it’s a question of people who are not afraid of the state penetrating and changing the state.” This is starting to happen with the post-revolution generation of young leaders from 20 to 45 years of age, he said.

“In order to modernize, you can’t have a state that is dysfunctional. It has to work better and people have to trust that the state can work better,” Snyder said. “It’s definitely a problem here.”

Ukraine’s leaders, such as President Petro Poroshenko, can help by letting the younger generation come to power rather than fearing and threatening them. The oligarchs can also play a helpful or harmful role in the nation’s development.

“Oligarchs themselves have to think: ‘What is my legacy?’ It’s not like we’re going to take their money away,” Snyder said. They have to ask themselves: “Am I going to be remembered as a state builder or am I going to be remembered as a schmuck?’ They have plenty of time and money to think about it.”

And the West, he said, has an obligation to stay engaged with Ukraine — not just for what it can give, but for what Ukrainians can give — and keep persistently pushing for positive reforms and change. “We in the West can’t afford to back out,” he said.

Healing or exploitation?

The third connection between past traumas and present realities is that politicians have abundant opportunities to exploit or heal societal divisions.

“You have many more possible opportunities for political actors to divide society. That’s a risk,” Snyder said. But there’s a positive side if people and politicians “look at each other and say these (historic events) are all pieces of the puzzle that we can talk about.” Ukraine needs to have this national dialogue, he said.

On this score, the elaborate events to commemorate Babyn Yar’s 75th anniversary, backed by the state and financed by public and private sources, is a healthy development for Ukraine, he said.

“Things on this scale don’t happen very often. It’s a very good thing for different reasons,” Snyder said. “This is where (the Holocaust) started. This is where half of it happened and this is where we learned what people are capable of.”

He said the Ukrainian nation “is being built all the time” and the decision to elevate the victims of the past was “a pretty big choice” to signal the current values and future direction of the state. “It was a very good choice,” he said.