ZHYTOMYR, Ukraine — Altars, candles, and prayers have become a daily routine for President Petro Poroshenko and his retinue, who since Jan. 10 have followed him in a roadshow around Ukrainian churches, which some mockingly call his “Tomos Tour.”

Tomos is the handwritten parchment decree granting official recognition to the newly formed Orthodox Church in Ukraine, making it independent from the Russian Orthodox Church headquartered in Moscow.

Poroshenko, who lobbied hard for this religious separation from Russia, has been traveling to various Ukrainian cities and showing people the precious parchment.

To make sure everyone knows of this achievement, special billboards were placed around Ukraine. They show Poroshenko smiling next to the tomos and Metropolitan Epiphanius, the leader of the new Ukrainian church.

The “Tomos Tour” looks more like campaigning for his March 31 re-election, rather than a “working trip,” as it is formally called. Poroshenko is expected to officially enter the race by the Feb. 3 deadline for registration.

Oleksandr Kliuzhev, an analyst of Opora election watchdog, said there are grounds to say the tour is “linked to information campaign in favor of candidate Petro Poroshenko.”

Political analyst Volodymyr Fesenko called it “one of the main tools of his presidential campaign.”

But the president’s status allows Poroshenko to travel on the taxpayers’ money and benefit from the subservience of local authorities. Poroshenko’s spokespersons either refused to comment or ignored the Kyiv Post questions regarding Poroshenko’s tour and his billboards.

Tomos in Zhytomyr

In Zhytomyr, a provincial capital of 267,000 residents located 140 kilometers west of Kyiv, Poroshenko demonstrated tomos on Jan. 17.

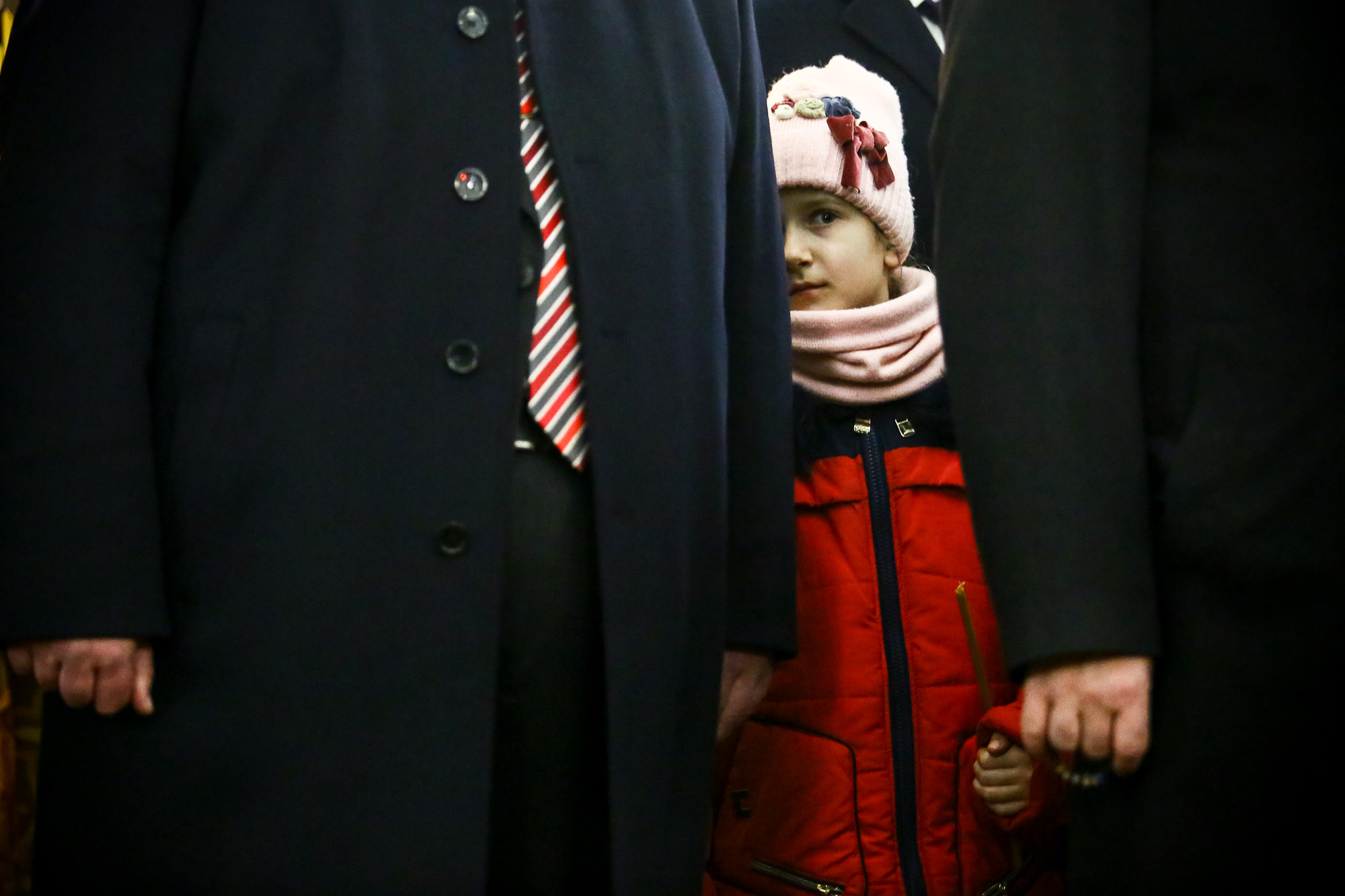

Up to 200 people, including priests in gilded gowns, worshipers, children from a Sunday school, teenagers from a local folk choir, and journalists patiently stood for about an hour in the 19th century St. Michael (Mykhailivskiy) Cathedral, waiting for his arrival.

“It was tiring, very tiring,” said 18-year-old Yana Minych, a student of a local culture and arts college and singer of a student choir that entertained the president with Christmas carols.

Poroshenko patiently stood during an hour-long church service, surrounded by a local mayor, a regional governor, Deputy Prime Minister Hennadiy Zubko and two lawmakers.

From time to time, the president was crossing himself or checking his phone. A massive Louis Vuitton logo on his shoes stood out from the attire of most parishioners.

In his speech, Poroshenko compared tomos with the act of Ukraine’s independence of 1991 and said it was his duty as a president to gain Ukrainian independent church.

“A united country is impossible without a united church,” he said. Ukraine’s Constitution, of which the president is a guarantor, rules that Ukraine is a secular state.

The priests were continuously thanking Poroshenko in prayers and speeches. The parishioners were more critical. Many came to the cathedral just to see a rare spectacle.

“My granddaughter wanted to see Poroshenko live,” said 69-year-old retiree Halyna Lukyanenko, standing along with her five-year-old granddaughter. The woman said she will vote for Poroshenko “because he loves Ukraine.”

Another retiree Vasyl Radchuk, 72, came out of curiosity. He was at home watching TV when he saw Poroshenko speaking in his city. He got up and boarded a trolley bus to the cathedral. He was too late to see Poroshenko but managed to see tomos.

Radchuk said he believed Poroshenko did a lot for the army but added that he “definitely wouldn’t vote for him.”

“He’s a millionaire. He profited and keeps on profiting out of others,” he said.

Minych said she would vote for “someone new” but hasn’t decided for whom exactly.

Who’s paying?

So far, Poroshenko has demonstrated tomos in Rivne, Vinnytsia, Lutsk, Kivertsi, Zdolbuniv, Boryspil, Zhytomyr, Cherkasy, sometimes arriving there by plane, sometimes by his motorcade. On Jan. 26, he is expected to bring tomos to Bila Tserkva, a website My Kyiv Oblast reported citing its sources.

Any trip like this involves hundreds of people, including the staffers from Presidential Administration, presidential security service, police, Security Service of Ukraine, and local administrations, according to diplomat Bogdan Yaremenko, who used to head the protocol of the prime minister in 2004–2006.

Yaremenko, who now heads a Kyiv branch of Ukrop party, backed by billionaire oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky, wrote about Poroshenko’s trips on Facebook. He claimed that every trip like this costs millions of hryvnias of state funds.

Poroshenko’s two spokesmen ignored Kyiv Post’s requests to comment on the cost of the trips.

Unlike other presidential trips, the schedule is being held in secrecy. Local journalists and parishioners get information about Poroshenko’s visits either from churches or from local administrations, sometimes just hours ahead of trips.

Poroshenko didn’t talk to journalists there but instead held comfortable closed-door meetings with loyalists.

After his trip to Zhytomyr on Jan. 17, he visited Berdychiv and had a closed meeting at a local music theater with people specially brought there by 13 buses from other cities of Zhytomyr Oblast, observers from Opora watchdog reported.

Earlier Opora also claimed that people were brought by buses to meetings with Poroshenko in the cities of Lutsk and Kivertsi.

“There are grounds to think that these trips were organized by the local authorities,” said Kliuzhev of Opora, adding that these cases need to be further investigated.

The observer is also concerned with the billboards of Poroshenko and tomos.

“It’s a good question where the money comes from for this political advertisement,” he said.

Placement of one billboard ad in Kyiv costs about Hr 17,000 (or $600) for a month, a marketing specialist told the Kyiv Post without giving his name because he wasn’t authorized to talk to the press. When a candidate wants to place billboard ads in the big Ukrainian cities for a month, he or she will have to pay a minimum of Hr 1 million (more than $35,000), according to the same source.

Lawmaker Sergii Leshchenko in summer 2018 published a document proving that some of Poroshenko’s billboards with the slogans “Army, language, faith” have been placed by the local authorities as social advertising, free of charge. The law on social advertising rules that a person or organization can’t place an ad that features this person or organization.

In November, the Presidential Administration denied placing any ads of Poroshenko on billboards.

Tomos and new voters

Despite all the secrecy and precautions, Poroshenko experienced an unpleasant moment in Cherkasy on Jan. 18, when a local activist Oleg Lysak asked when the president was planning to fight corruption.The answer was clumsy.

“Go to church, light a candle, for you are a non-believer. And the Lord will soothe you,” Poroshenko said.

But Volodymyr Fesenko, a political analyst, believes the scandals like this would not scare off people who were planning to vote for Poroshenko.

The ratings Democratic Initiatives Foundation and Razumkov Center published in late December revealed that Poroshenko’s rating increased and put him second after former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko. Other ratings, however, show him being between third and fifth place.

Sociologist Inna Volosevych, deputy director of Info Sapiens research company, said that although Poroshenko has improved his rating, likely thanks to the church topic, his campaign lacks economic issues to lure the electorate.

Fesenko said it’s still unclear if Poroshenko will even survive into the second round. Now he competes for a second place with comedian Volodymyr Zelenskiy, former defense minister Anatoliy Grytsenko, and Yuriy Boiko, a former ally of ousted President Viktor Yanukovych.

But his chances are high.

“His active and massive campaign is an important tool,” Fesenko said. “Moreover, he has control over the election process.”