WASHINGTON — Author and historian Vakhtang Kipiani heads Istorychna Pravda (“Historial Truth”), a project that seeks to shed light on episodes in Ukraine’s past that have been “lost” or deliberately obscured by the country’s colonial masters over the centuries.

Now he has taken that quest to the United States to promote a new book about the last Ukrainian political prisoner to die in the Soviet gulags, the poet Vasyl Stus.

In October Kipiani presented the book to Ukrainian diaspora audiences in Washington, New York City, Pennsylvania and Connecticut, and he will visit other cities in America and Canada this month.

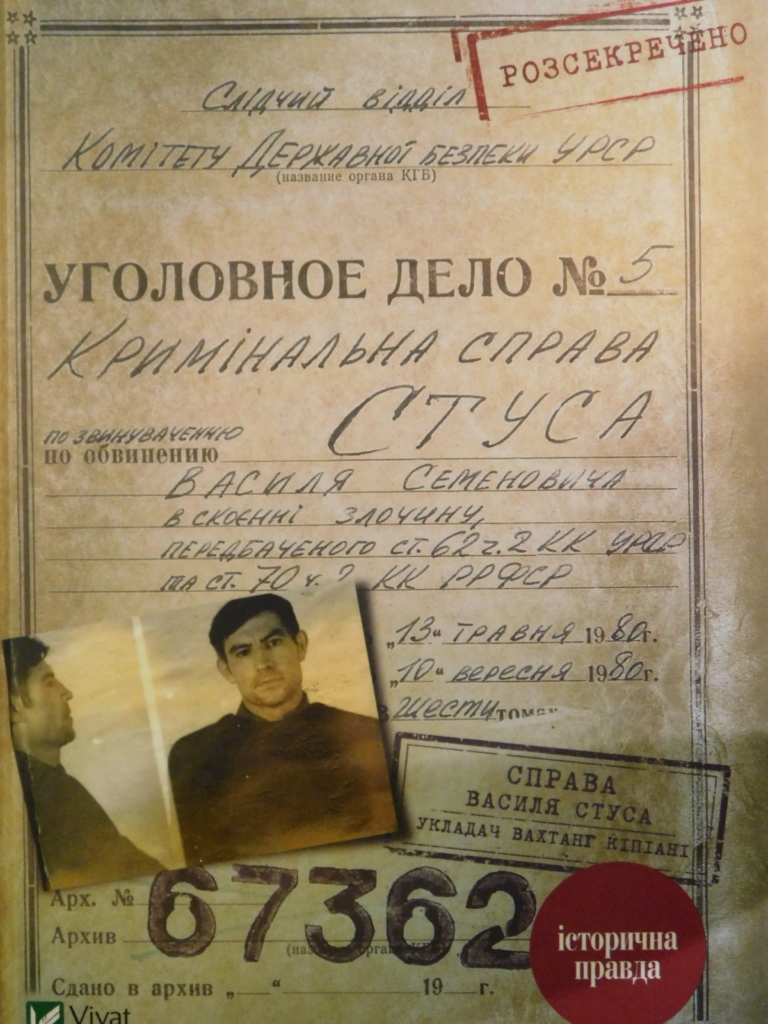

The book, called “The Case of Vasyl Stus,” is based on six volumes of material about the investigations and persecution of pro-democracy dissidents in the Soviet Union gleaned from the archives of the Ukrainian KGB, which were opened to independent researchers in 2005. It examines those who tried to help Stus and those who worked to ensure he would disappear in the network of Soviet labor camps.

Stus, born to a peasant family in eastern Ukraine, was one of Ukraine’s most prominent pro-democracy dissidents struggling for human rights. He was also a gifted poet, and his writing criticized the harsh Soviet system and reflected his love for Ukraine. At a time when the Soviet regime demanded that artists praise communist heroes, preferably in Russian, Stus’s Ukrainian poems became a thorn in the Kremlin’s side. For that, he was eventually persecuted.

Stus served 13 years in the gulag before he died during his second sentence 1985 at the age of 47, supposedly of ill health.

The cover of Vakhtang Kipiani’s book features images from the KGB ‘s file on Vasyl Stus, who died in a Soviet labor camp in 1985 after 13 years of imprisonment.

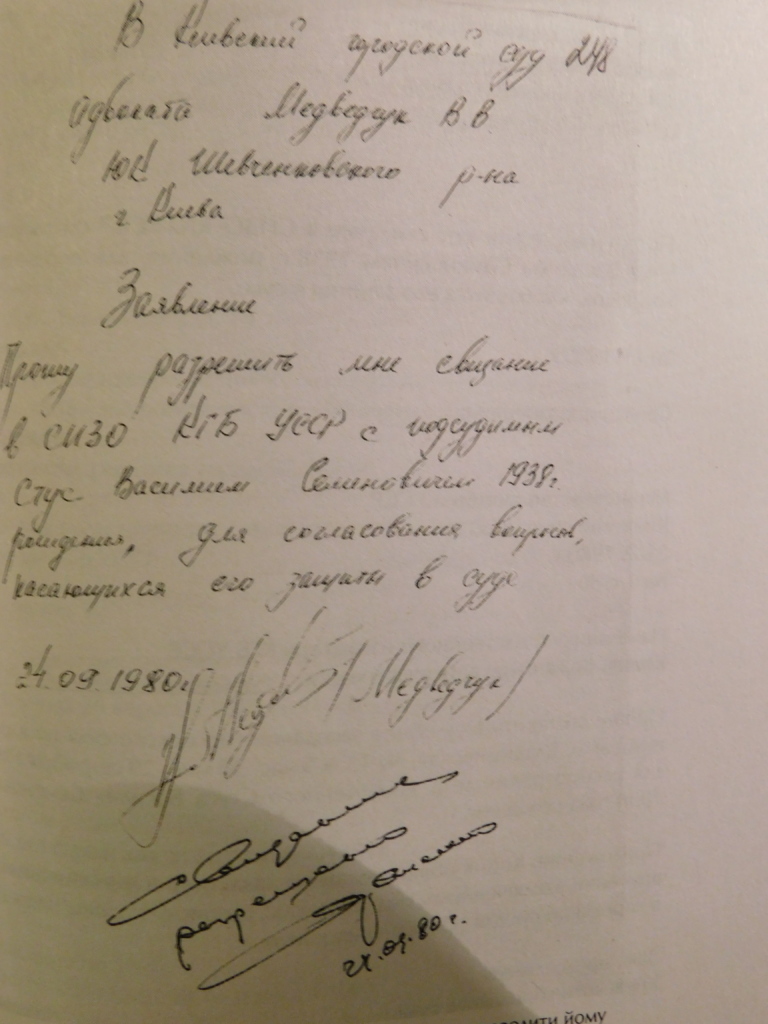

The book has become a best-seller in Ukraine, in large part because of attempts by the controversial oligarch Viktor Medvedchuk to suppress it. In 1980, Medvedchuk was a loyal communist party member and the lawyer appointed by the authorities to defend Stus against charges of “anti-Soviet agitation.”

Medvedchuk never attempted a real defense of his client, and Stus immediately recognized Medvedchuk as a willing cog in the oppressive system and spurned his services.

Medvedchuk dutifully performed his role, and in his “defense” stated that Stus indeed deserved punishment for his crimes but also deserved consideration for being a reliable worker at the factory where he was employed. Stus was found guilty and given a 10-year prison.

After the Soviet Union disintegrated in 1991, the formerly devoted communist Medvedchuk swiftly repackaged himself as a proponent of democracy and capitalism. Like many former party loyalists, he used his ties to the communist network to amass wealth during the privatization of state assets.

Medvedchuk also became one of newly-independent Ukraine’s most powerful politicians, always favoring close ties with Moscow. In 2002, he became the chief of staff for former President Leonid Kuchma, whose authoritarian rule was known for rampant corruption.

Medvedchuk would go on to forge a friendship with Russian President Vladimir Putin, who is the godfather to his daughter. Since Russia invaded Crimea and launched a war in the eastern Donbas in 2014, Medvedchuk has flitted between Kyiv and Moscow and has been widely criticized as Putin’s man in Ukraine.

After presenting his book at the Ukrainian Catholic Church in Washington, Kipiani spoke with the Kyiv Post about Stus’s role in resistance to the Soviet regime. He explained that Stus’ poetry and other writings were never permitted to be published by the Soviet authorities, but were widely read in samvydav — the Ukrainian name for samizdat, or underground, dissident publications.

Such writings were regarded by the Kremlin as acts of rebellion, and hundreds of those involved in producing or distributing them were sent to remote prison camps.

This year, Medvedchuk began legal proceedings in an attempt to halt the distribution of Kipiani’s book, alleging that it contains incorrect information about his role in Stus’s imprisonment.

Court hearings began on Oct. 2, and Kipiani said the next hearing is expected on Dec.13. His lawyers say there will probably be between four and six hearings, which should conclude toward the end of 2020. So far, Medvedchuk has not demanded compensation from Kipiani, however, the historian’s lawyers warn that should Medvedchuk be successful in court, he might demand hundreds of thousands of dollars to cover his legal costs.

That, said Kipiani, could potentially inflict great financial harm to the Istorychna Pravda project. “I hope that the court procedures will be honest,” he told the Kyiv Post. “The first hearings don’t give grounds to suspect otherwise. The judge seems well-acquainted with the information and acted according to the law.”

Last year, in an interview with the British newspaper the Independent, Medvedchuk justified Stus’s persecution. “Stus denounced the Soviet government and didn’t consider it to be legitimate,” he said. “Everyone decides their own fate. Stus admitted he agitated against the Soviet government. He was found guilty by the laws of the time. When the laws changed, the case was dropped. Unfortunately, he died.”

Previously, the full record of Stus’s trial had been missing, with information pieced together from fragments of documents and snippets of conversations.

“We thought that Medvedchuk had behaved badly, but a lot of it was at the level of hearsay,” Kipiani told the Kyiv Post. “But here we have documents and transcripts typed by KGB personnel in which Stus calls the Soviet system ‘diabolical’ and ‘fascist’ and that the Soviet government is on the side of evil.”

One of the documents showing how oligarch Viktor Medvedchuk worked with the KGB in his sham defense of Vasyl Stus.

Kipiani and his colleagues worked through masses of documents that dealt with one-sided court procedures, not only against Stus, but also many other political prisoners sentenced after sham trials.

“The documents show how cynically witnesses lied in their testimony against Stus, show Stus’s defense of other political prisoners and we see the way Stus’s defense lawyer [Medvedchuk] behaves in a way to portray his client as guilty.”

“[The trial] had the appearance of being done correctly, according to Soviet law, but the underlying fact was that it was done on the orders of the Communist Party’s Politburo (executive body) in order to undermine the dissident movement throughout the USSR,” Kipiani said.

Under Ukraine’s previous government, Medvedchuk had an official role in the Minsk accords, where he was seen as representing Putin. Kipiani believes that Ukrainian intelligence agencies should take a closer look at Medvedchuk and open investigations about what many regard as his betrayals of Ukraine.

“They should ask how Medvedchuk was able to visit, in Moscow’s Lefortovo prison, 34 Ukrainian sailors captured last year by the Russian Navy, when lawyers for the Ukrainian prisoners were not given access to them,” he said. “It shows he is allowed to conduct political work on the territory of the Russian Federation.

“In my opinion, during a time of war, this indicates that he has gone over to the side of the enemy. But the SBU (Ukrainian security agency) obviously doesn’t see it the same way, and Medvedchuk feels wonderfully unfettered in his politics and business.”

Kipiani said that his book on Stus had attracted significant interest with larger-than-average sales in Ukraine even before Mevedchuk’s attempts to ban it gave it a huge jolt of publicity, prompting an additional rise in sales.

“Society reacted to Medvedchuk’s attempts to kill off the book by buying it in large numbers,” he said. “People have bought copies so that they can keep them safe in their own homes. Medvedchuk won’t be able to get at them, whether it’s the copy that is now in the U.S. Library of Congress in Washington or in someone’s home in Kolomyia or Buchach.

“Medvedchuk is widely thought of as a hostile political force and an odious figure. If Medvedchuk is against something, most people will be for it.”

Besides promoting his book, Kipiani also sees his meetings with the Ukrainian diaspora as an opportunity to gather items from around the world for a press museum he is creating in Kyiv. He has also publicized the formation of an endowment to maintain and develop Istorychna Pravda. Some funds have already been collected among the diaspora, notably by the New York-based Razom group.

Istorychna Pravda posts huge amounts of historical documents, widely-acclaimed analysis, and other materials online. It also presents a weekly television program.

Kipiani said other books are in the pipeline about various Ukrainian and non-Ukrainian Soviet-era dissident groups, as well as a book that will pay tribute to the Rukh pro-democracy movement, which operated in the 1980s and 1990s, which, he said, shifted Ukraine’s pro-democracy struggle towards a fight for independence.