Editor’s Note: This is the third story in the Kyiv Post’s “Honest History” project, a series of stories and videos that debunk myths about Ukrainian history used by propagandists. The series is supported by the Black Sea Trust, a project of the German Marshall Fund of the United States. Opinions expressed do not necessarily represent those of the Black Sea Trust, the German Marshall Fund or its partners.

DROHOBYCH, Ukraine — At the top of Drohobych’s city hall, in this city of 76,000 close to the Polish border, two Jewish girls escaped the Holocaust by hiding beneath the gears of the town’s bell tower.

They were in there for three years, say townspeople — from when the Nazis took the city in 1941 to when the war ended there in 1944. They survived, but were left deformed. Their spines were twisted from crouching, and they were partly deaf because of the constant ringing of the bell.

Russian propagandists would have people believe that those girls were hiding from the same type of people who organized the 2014 EuroMaidan Revolution — genocidal supporters of Ukrainian nationalist leader Stepan Bandera, intent on creating an ethnically pure Ukrainian state.

But that’s a mendacious description of EuroMaidan, which deposed Kremlin-backed President Viktor Yanukovych in 2014, and of the Ukrainian government in power today.

The history of World War II in Ukraine is more complicated than the story of Bandera. Russian propaganda plays off the very real involvement of Ukrainian nationalists in the mass killing of Jews, and gains credibility from the country’s failure to come to terms with these crimes.

But in western Ukraine, Bandera’s old heartland, views of history — and Ukraine’s role — are shifting. Ukrainians are starting to organize memorials and events commemorating their lost Jewish community, the one-third of their population that was exterminated during World War II.

Drohobych holds a biannual Bruno Shulz festival to commemorate the Jewish writer and painter who was killed by a Nazi bullet in 1942. Lviv is undertaking an ambitious project to build three Holocaust memorials.

Many of those involved in efforts to commemorate the Holocaust see recognition of responsibility as the best path towards both European integration, and to gutting Russian propaganda’s main thesis — that being a Ukrainian patriot is equivalent to being an unrepentant anti-Semite.

Breaking myths

But how does a country fight back when enemy propaganda is based — at least in part — on real events?

Volodymyr Sklokin, a historian at Lviv Catholic University who focuses on public history, points out that Ukrainians — and Ukrainian nationalists — had varied roles in World War II.

“Almost all of Europe, it seems, has recognized that it took part in the Holocaust,” he said. “But the guilt of certain people, possibly the OUN (Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists) or UPA (Ukrainian Insurgent Army), does not discredit the whole Ukrainian national movement, nation, or state.

“There were Ukrainians that fought in the Red Army, the Polish Army, in other nationalist groups, and who saved the Jews, like Andriy Sheptytsky,” he added, referring to the Lviv archbishop who sheltered Jews during the German occupation. “To say that everything comes down to UPA and OUN contradicts historical facts.”

A magnet for Kremlin propagandists is the figure of Bandera, usually deployed as an anti-Semitic bogeyman. Though not on Ukraine’s territory during World War II, Bandera was a charismatic figure around which some Ukrainian partisans could rally, and remains glorified today in many parts of the country. But his road to cooperation with the Nazis — and his leadership in Ukraine’s national movement — came from complex roots.

Lviv Historical Heritage Protection Chief Lilya Onishchenko gestures with a stone in her hand at the Golden Rose synagogue memorial. Onishchenko plans to start building an extension of the memorial on the square behind her as part of a larger project to expand Lviv’s Holocaust memorial sites. (Kostyantyn Chernichkin)

Bandera was brought up in the 1920s, when the Ukrainian population was split between the interwar Polish republic and the Soviet Union. He and other Ukrainian nationalists born on the Polish side — which now includes Galicia and Volyn — came up at a time when ethno-nationalism was rampant across Europe, and Ukrainians were living in subjugation.

The OUN, formed in 1929 from the Ukrainian Military Organization, reacted to what it viewed as Polish subjugation. It committed itself to underground terrorism against the Polish state, assassinating officials in a bid to create a separate Ukrainian state, but was initially ambivalent toward the Nazis.

This changed. The OUN split in 1941, with Bandera heading the OUN-B, a more militarized faction enthusiastically backed by Galician youth.

Meanwhile, as German power grew, this generation of far-right Ukrainian revolutionaries, in order to have a shot at independence, were willing to overlook aspects of the Nazi vision for Europe that repelled other Ukrainians. The Nazi Generalplan Ost — the Third Reich’s master plan for ethnic cleansing in Eastern Europe — called for 65 percent of Ukrainians to be exterminated or deported to Siberia, with the rest to remain as slaves.

When the Soviets invaded eastern Poland under the secret annex to the 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, the OUN began insurgent activity against the new Soviet occupiers, and the Germans saw an opportunity: in spring 1941, the OUN began to receive financing from Nazi intelligence. Germans began to train two Ukrainian volunteer battalions in the Nazi-controlled portion of occupied Poland.

Catastrophe

What happened next was unmistakably brutal.

War came to Galicia in June 1941, as German tanks rolled into the territory along with the two OUN battalions.

“The Jews were overcome with terror,” wrote David Kahane, a Lviv rabbi who survived the war thanks to the efforts of Archbishop Sheptytsky. “The horrors perpetrated…in Lviv, however, were to surpass our wildest imaginings. No one had guessed the enormity of the defeat and the thoroughness of the extermination.”

OUN-B leader Bandera, then based in Krakow, Poland, sent his deputy Yaroslav Stetsko to declare the creation of a Ukrainian state in June 1941.

A German-Ukrainian parade in Ivano-Frankivsk in July 1941 during Nazi occupation. Ukrainians are slowly coming to terms with the mass murder of Jews in Ukraine during World War II. (Courtesy)

Entering Lviv in the aftermath of the German invasion, Stetsko issued a “proclamation of Ukrainian Independence” on June 30 in Bandera’s name, stating that “the restored Ukrainian state will closely cooperate with the National Socialist Greater Germany, and that under its leader, Adolf Hitler, a new order will be created in both Europe and the world that will help the Ukrainian people be liberated from Muscovite occupation.”

As the Nazis assumed control over Galicia, they reorganized the OUN battalions into a force called the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police. Then in the early days of July 1941, the Germans incited the Lviv pogroms, in part by fabricating evidence that murdered Ukrainian prisoners had been killed by Jews, and not by the Soviet secret police, the NKVD, as had actually happened.

The Nazis were also able to play on local blood libels implicating a “Jewish-Bolshevik” conspiracy in the Holodomor.

Jews were taken out of their homes and beaten in the streets. Thousands were shot by German, Polish and Ukrainian killing squads, with OUN members taking part, according to eyewitness accounts.

“They walked in silence, weighed down by their suffering and woe. Doomed,” wrote Kurt Lewin, a survivor of the episode. “From either side, the better people looked on — Aryans, Poles, and Ukrainians.”

By summer’s end, the Germans, vexed by Stetsko’s independence declaration, had arrested him and Bandera, and disbanded his forces.

“We were also able to establish that the Ukrainians had done a pretty good job plundering,” wrote Felix Landau, an SS commander based in Drohobych in a July 1941 diary entry. “They had really thought they were the masters for a while.”

With many OUN-B members under arrest by the Germans, the remnants formed the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, known by its UPA acronym, in 1942. The UPA moved out of the cities and fought from forest hideouts.

It is unclear whether post‑1941 incidents of anti-semitism were widespread and directed by UPA command, or if they were isolated and uncontrolled. Documents and eyewitness accounts often contradict each other.

One trove of documents, for example, records references to “Jewish-bolshevik scum,” and one internal OUN document ends with the phrase “long live Stepan Bandera, long live Adolf Hitler.”

Other internal political instructions state: “We are not against the Jews” and “do not kill Jews.”

Dieter Pohl, a German academic who has extensively studied the issue, said that there was “limited institutional collaboration” in the Holocaust, and added that “the UPA groups were not centralized.” Survivor accounts say that some Jews would flee Nazi purges in their villages only to be attacked by UPA fighters in the forests, while others were conscripted into insurgent battalions.

All in all, only 800 Lviv Jews were left alive out of a pre-war population of 200,000, and another 800 in Drohobych out of a pre-war population of 15,000, with as many as 1.5 million Jews killed across Ukraine.

Reconciliation?

Some Ukrainians argue that they’re held to an unfair standard.

“With the Germans, (anti-Semitism) occurred at the level of state policy,” said Andriy Kohut, the director of the SBU archive and a former researcher at the Center for the Study of the Liberation Movement.

“What do modern Ukrainians need to recognize? That they participated in this? They weren’t alive then,” he later added.

Many efforts at commemoration follow this approach — attempting to reflect the tragedy of what occurred without assigning blame.

For instance, Lviv is building a new museum called the “Territory of Terror,” which aims to communicate how trauma transformed the city from 1930 to 1950.

Like many other museums in the region, it draws an equivalence between Nazi and Soviet brutality. The museum, located on the spot where Jews boarded trains to the Belzec extermination camp, includes a train wagon used both to transport people to Belzec and to move political prisoners to Siberia after the Soviet victory.

“In the 1990s, a situation developed in Ukraine where each national tragedy was only a tragedy for each national group,” said Ihor Derevianyi, a curator of the museum. “We’re now at a negative moment where we have a conflict of memory, when every group thinks that its trauma is more important than the trauma of another.”

“Our museum wants to show the traumatic past of different groups, and to show that pain is universal, without national markers,” he added.

Territory of Terror museum scholar Ihor Derevianyi speaks at the Lviv museum where he works. The museum, which features a replica of the train station where the Lviv Jews were transported to the Belzec extermination camp, will open in October. (Kostyantyn Chernichkin)

But others see recognition of guilt as necessary, both as a way to counter Russian propaganda, and to better understand unresolved pieces of Ukrainian identity.

“Nobody says that you have to erase OUN-B from the history of Ukraine,” said Sofiya Dyak, Director of Lviv’s Center for Urban History. “But it’s worth giving an account of what their agenda and values were. They were from the middle of the 20th century — do we need them in the 21st century? That’s an important question.”

“Ukraine is a complex and beautiful country, and if you start saying you like some people, while others should go, it’s very hard to build a diverse society that can live together,” she added.

Both Sklokin, the Catholic University professor, and Pohl, the German historian, pointed out that the European Union forced countries like Latvia and Romania, when they were in the process of accession to the EU, to investigate and repent for crimes committed during World War II.

“It’s not always the task of Western historians to investigate dark spots in national history,” Pohl said. “It should be the task of the Ukrainians themselves.”

Attempts to come to terms with this past still trigger debate.

Lviv last year dedicated a memorial at the spot where its Golden Rose Synagogue once stood: the synagogue was burned down by the Germans in 1941.

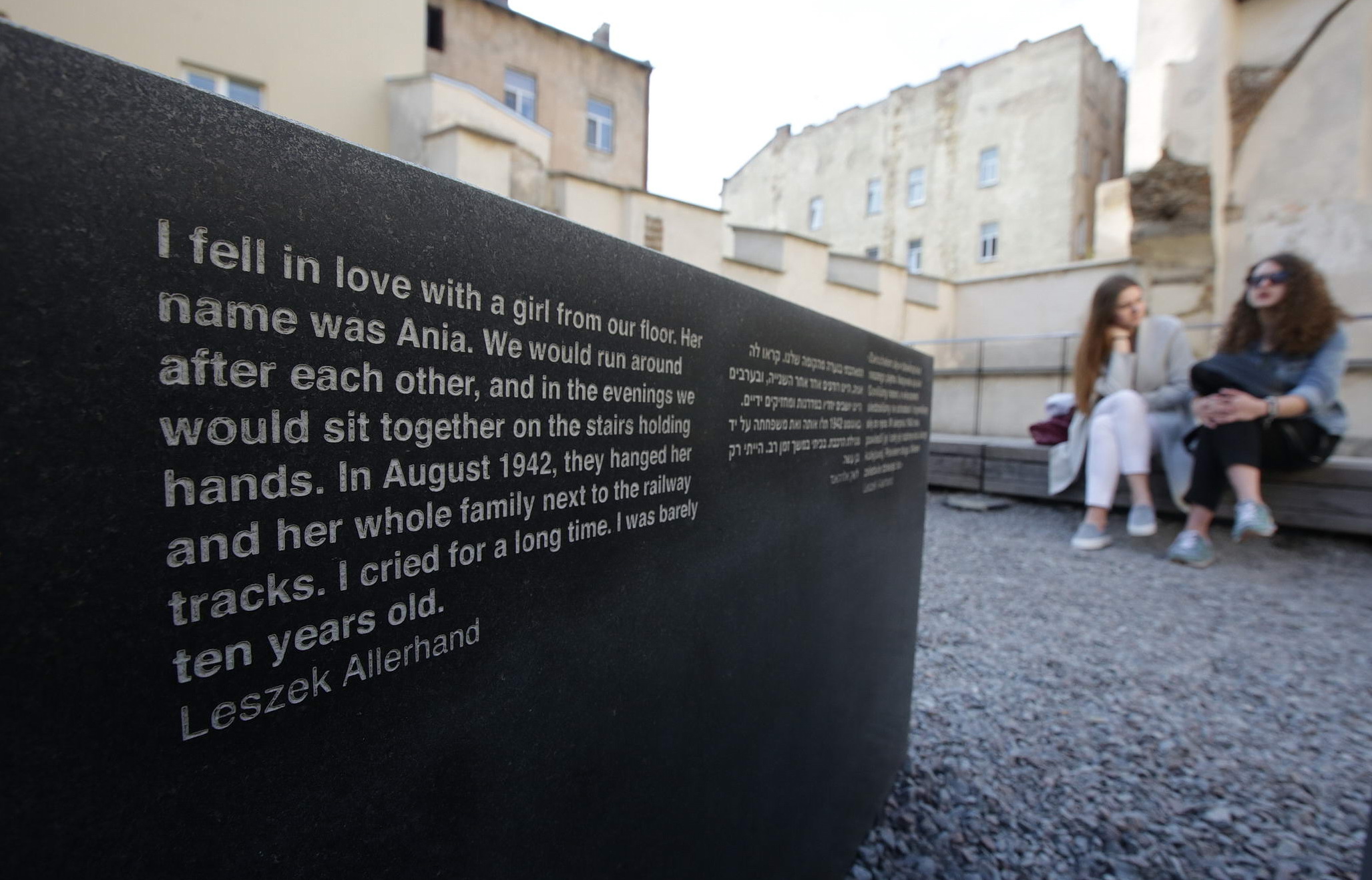

But the Golden Rose memorial has been subject to controversy. The monument contains dozens of stone slabs with quotes of different Holocaust survivors, historians, and people involved.

Some, like Orthodox Jewish activist Meylakh Sheykhet, have argued that the memorial does a disservice to the city’s heritage, and that the only fitting memorial would be a full reconstruction of the synagogue.

Sheykhet threatened to sue the project over one quote cited above in this article by Holocaust survivor Kurt Lewin, alleging that the portion of the quote mentioning “Poles and Ukrainians” would violate a law against interethnic hatred.

The project organizers responded by removing the end portion of the quote saying that “Poles and Ukrainians” were involved in the Lviv pogrom, with the citation instead pinning the blame only on “Aryans.”

According to Liliya Onischenko, head of Lviv’s department for historical heritage protection, the city plans on building two more memorials — at the old Jewish cemetery, and the Janowska concentration camp.

“It’s a very painful issue for us, that Lviv lost so many of its citizens during World War II, and that their memory in Lviv is not quite present,” she said. The Golden Rose memorial “symbolizes the void left by the Jews who no longer exist.”

Correction: A previous version of this article misstated Andriy Kohut’s position as Director of the SBU Archive. The error has been corrected.