For 22 Ukrainian navy sailors and 2 counter-intelligence operatives, 286 days in Russian captivity are finally over.

Together with other 11 civilian captives held by the Kremlin for years, they were brought back home on Sept. 7 — as part of a big prisoner exchange between Russia and Ukraine — cheered by jubilant crowds on a Boryspil Airport runway strip.

Just weeks, if not days, before their glorious return, few really considered this a realistic outcome.

“Finally, what we have been fighting for over nine months has happened,” as Nikolay Polozov, the leader of a team of Russian lawyers defending the Ukrainian sailors, said on Sept. 7.

“It has become possible thanks to the tenacity and personal courage of the sailors, as well to the work of a huge number of people who travailed around the clock towards the result… Each of my colleagues understood that this case was complicated and “toxic,” and that it can precipitate destructive effects for a defender. But no one among them wavered or faltered. Each of our lawyers was consciously drawing his or her duties.”

The sailors’ ordeal began with Russia’s infamous attack against three Ukrainian navy vessels — tugboat “Yany Kapu” and two small gunboats “Nikopol” and “Berdyansk” — in the Black Sea on Nov. 25, 2018. Set sail from Odesa to the Azov Sea port of Mariupol, the naval group was haunted and blocked by Russian coast guard close to the shores of Russian-occupied Crimea and eventually fired upon near the Kerch Strait — the gateway to the Sea of Azov aggressively grabbed by Russia.

Russian warships supported from the air were shooting to kill and wounded six Ukrainian in short though brutal confrontation with barely armed Ukrainian vessels. Eventually, a Russian special task team arrested the sailors and drove their ships to the occupied port of Kerch.

The Ukrainians eventually ended up in the Lefortovo jail in Moscow, facing accusations of “violation of the Russian border.” None of them officially admitted guilt to the Russian investigation, and each of them declared himself a prisoner of war. Many of them refused to give testimony.

Their will was something that Russians found really difficult to break: Many of the captured sailors once remained committed to their oaths of allegiance to Ukraine during Russia’s invasion of Crimea of 2014. Back then, unlike many fellow servicemen in the peninsula, they refused to defect to the Russian navy.

And years later, in the Moscow prison, they reiterated their allegiance once again.

So here’s what we know about those 24 servicemen who have got through 286 days in captivity staying loyal to their flag.

Nikopol gunboat crew

Bohdan Nebylytsya, 25, first lieutenant (OF-1)

Nebylytsya was the commanding officer of “Nikopol.”

He studied at the Nakhimov Naval Academy in Crimea, but his training was aborted amid Russian invasion. He was among a handful of cadets singing the Ukrainian national anthem as their academy was raising the Russian colors. Nebylytsya refused to defect to the Russian navy and continued his education in Odesa.

In 2016, he was appointed to command the missile boat Prylyky and later to “Nikopol”. As a talented young officer, Nebylytsya was supposed to receive training in the United States and take the lead of one of two Island-class patrol boats provided to Ukraine at no cost by U.S. Coast Guard.

Serhiy Tsybizov, 22, seaman (OR-1)

One of the youngest crewmembers.

Tsybizov was one of three sailors videoed by Russian admitting to having “violated Russian territorial waters” in Crimea. Nonetheless, after those videos were published in Kremlin-controlled media, Admiral Voronchenko dismissed these “confessions” as predictably given under pressure put by Russian FSB security service.

Later, however, Tsybizov declared himself a prisoner of war and refused to cooperate with Russian prosecution, according to lawyer Nikolay Polozov.

Serhiy Popov, 28, captain-lieutenant (OF-2)

Originally from the city of Donetsk, Popov studied and served in Ukrainian navy in Crimea and left the peninsula for Odesa in 2014.

According to the officer’s lawyer Ganzhi Aliyev, Popov used to ridicule Russian prosecution and often reiterated that he outranked his inquiry officer interrogating him in jail.

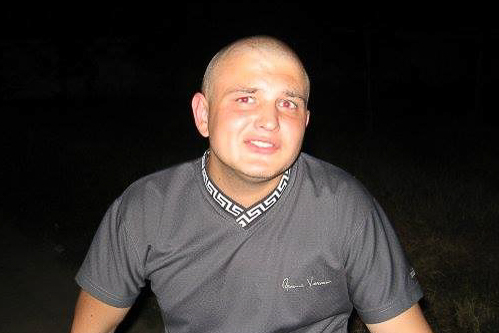

Vyacheslav Zinchenko, 21, senior seaman (OR-2)

One of the youngest sailors captured in the Nov. 25 incident. At that time, he was only making his first steps in naval career: He planned to enroll at the Odesa Maritime Academy next year. According to lawyer Polozov, the young sailor was seriously upset he couldn’t become a cadet while languishing in jail.

Upon his arrival in the Boryspil Airport, Zinchenko told journalists he dreamed of seeing the sea again, but added that he was not yet ready for another maritime mission.

Andriy Oprysko, 47, senior seaman (OR-2)

Oprysko came to serve the Ukrainian navy in 2016, when he was already in his mid-40s.

According to his defender Mammet Mambetov, Oprysko in planned to continue serving and get promoted to officership.

Vladyslav Kostyshyn, 24, petty officer 1st class (OR-6)

Kostyshyn is a student too: He was undergoing an internship as the Nikopol’s navigator. He was one of the best cadets of his class at the Odesa Naval Academy and was expected to get promoted to the rank of lieutenant in early 2016.

According to lawyer Polozov, Kostyshyn compelled the Russians to provide him with Russian-Ukrainian interpreter. He loves boxing, and while staying behind bars, he also asked his lawyer to keep him updated regarding the latest boxing matches.

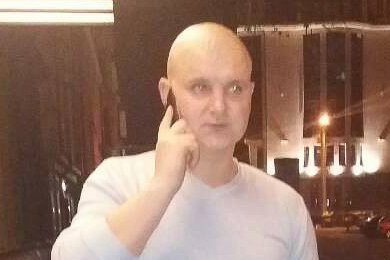

Andriy Drach, 24

Drach was one of two SBU security service officers commissioned to the naval group to ensure the mission’s counter-intelligence support. Drach also was among those few Nakhimov Academy cadets who remained loyal to Ukraine in 2014. Following the arrest on Nov. 25, he was videoed by Russians saying that the group’s ships entered the Russian territorial waters near Crimea after numerous warnings from the Russian coast guard.

Unfortunately, his father died of heart issues while his son was being held captive in Moscow.

“Yany Kapu” tugboat crew

Oleh Melnychuk, 24, petty officer 1st class (OR-6)

Melnychuk was the commanding officer of “Yanu Capu” tugboat. It was his vessel that was viciously rammed by attacking Russian coast guard warships on Nov. 25, with Russian command yelling “Crush him!”

Melnychuk refused to speak Russian with his interrogators and demanded that an interpreter be called for him.

Yevgen Semydotskiy, 20, seaman (OR-1)

Semydotskiy is originally from the Luhansk Oblast. He was born in the town of Troitske, which is now divided by halves by the frontline of Russia’s war in Donbas.

According to layer Polozov, Semydotskiy gave his prison cell-mate lessons in Ukrainian.

Serhiy Chuliba, 30, petty officer 1st class (OR-6)

Chuliba was the vessel’s engineer. Prior to 2014, he served on gunboat”Kherson”, which was blocked by Russian forces in the Donuzlav Bay during the invasion. He refused to defect.

According to Gennadiy Fedorov, his defender in court, Chuliba in the prison was really worried about Jessie — the crew’s pet dog (which was released by Russians on July 29, more than a month before the very sailors). Besides, he was afraid that in Russian custody, without due maintenance, his vessel’s technical condition would deteriorate.

Volodymyr Lisoviy, 34, captain 3rd grade (OF-3)

His wife and his little son were waiting for Volodymyr Lisoviy in Odesa for these 9 months.

Lisoviy was also videoed by Russians saying that the Ukrainian vessels were “taking provocative actions” during the Nov. 25 standoff. Ukrainian navy commander Admiral Voronchenko immediately dismissed these allegations as forced out by Russian investigators.

“Methods of Russian special services’ working are no secret,” the admiral said. “All naval sailors understand (what stands behind) the so-called evidence.”

Viktor Bespalchenko, 31, senior seaman (OR-2)

Bespalchenko, together with his crewmate Chuliba, used to serve on gunboat “Kherson” captured by Russian forces in 2014 in the Donuzlav Bay. And he fled the occupied peninsula to continue serving the Ukrainian flag.

Bespalchenko’s 9-month custody in Moscow was marked with a joyous moment — in June, married his bride Tetyana, who came to the Russian prison to see him.

Andriy Shevchenko, 29, midshipman (OR-9b)

Shevchenko gained fame for a stunt pulled on April 25 just in the Russian courtroom: While being kept behind bars, he put out a table congratulating his wife Anastasiya on her birthday and showed it before cameras broadcasting the trial live.

The namesake of the legendary Ukranian soccer champion Andriy Shevchenko, the naval officer is a huge sports fan. Upon his arrival in the Boryspil Airport on Sept. 7, he was wearing the colors of Dynamo Kyiv, the Ukrainian prime soccer club.

Volodymyr Varimez, 27, senior seaman (OR-2)

Varimez was the vessel’s communications operator. In 2014, he also was among those who fled the Russian occupation in Crimea, having successfully navigated their ship to Odesa.

Similarly to some of his fellows, he demanded being provided with a Ukrainian interpreter in the prison — although unsuccessfully.

Volodymyr Tereschenko, 25, senior seaman (OR-2)

He served in Crimea for a year before the Russian invasion, and also remained loyal to Ukraine.

In the Lefortovo jail, he managed to shave the Ukrainian trident on back of his head and was “shocking the jail’s personnel,” according to lawyer Anastasiya Georgiyevskaya.

Mykhailo Vlasiuk, 34, senior seaman (OR-2)

He started his career in the military as a cook at Independent Presidential Regiment in Kyiv, but later exchanged into navy. In 2014, he remained loyal to Ukraine — and was feeling extremely bitter about fellow officers and seamen defecting to Russia.

Yuriy Budzylo, 46, midshipman (OR-9b)

He was the longest-serving member of the naval group, with almost 30 years spent in navy. He was among those breaking the Russian blockade in 2014 in the Donuzlan Bay in Crimea.

Back then, it took him a week to return to the Ukrainian mainland together with his son Ivan, who was a navy sailor too.

Berdyansk gunboat crew

Roman Mokryak, 33, first lieutenant (OF-1)

Before the invasion in Crimea, Mokryak served 5 years on the Zaporizhia boat — the only Ukrainian submarine — and he refused to defect in 2014.

Instead, he left for Odesa and took the lead of the Prylyky missile boat. His next vessel, the recently-produced gunboat “Berdyansk”, was heavily damaged by Russian fire during the Nov. 25 incident. 6 of his crewmembers were injured.

In custody, he refused to provide testimony to FSB operatives and demanded that his crewmembers be released. He insisted that all accusation must be brought on him, the vessel’s commanding officer.

Andriy Artemenko, 25, senior seaman (OR-2)

Artemenko also declined to serve Russia in 2014. He was heavily wounded in the Nov. 25 attack: Russian missile fragments left severe injuries on his arms, eyes, and torso.

He was operated on in Russian-occupied Kerch shortly after the attack.

Andriy Eider, 19, seaman (OR-1)

Eider was the group’s youngest crewmember — at time of the attack, he was only 18. That was his very first mission.

He was severely wounded and operated on by Russians.

Denys Hrytsenko, 35, captain 2nd grade (OF-4)

Hrytsenko was in charge of the whole naval group crossing the Black Sea.

As with his fellow sailors, he did not break his oath of allegiance to Ukraine in 2014. During the Nov. 25 incident, Hrytsenko was said to be desperately giving SOS signals and reporting casualties from Russian fire. Nonetheless, Russian warships were continuing with their assault.

Upon his arrival in Kyiv, he told journalists he wanted to see the sea again.

Yuriy Bezyazychniy, 28, senior seaman (OR-2)

Son of a Ukrainian officer killed in action in Donbas, Bezyazychniy was studying in Odesa to get commissioned and simultaneously drawing active service duty in navy.

Following the Nov. 25 attack, his loved ones believed he was killed in action too, as his father was, — but fortunately, this assumption proved to be wrong.

Vasyl Soroka, 28, first lieutenant (OF-1)

Along with Andriy Drach, Soroka was an SBU operative ensuring the group’s counter-intelligence support.

The Russian attack left him badly injured in his left arm, which was almost completely disabled. According to lawyer Sergey Badamshyn, Soroka refused to testify to the Russian investigation.

Only months after, his arms started slowly recovering.

Bohdan Holovash, 23, senior seaman (OR-2)

He was studying in Sevastopol during the Russian invasion, and also refused to serve Russia.

He expected to be commissioned as a lieutenant in early 2019, but missed his finals in Russian custody. On the day he returned to Ukrainian soil, Holovash told journalists he wanted to return to active service as soon as possible and set sail for another mission.

When asked if he’d agree to cross the Kerch Strait again, he answered: “I will, if necessary.”