The World Bank highlighted key problems in its latest economic update for Ukraine, released on April 10. Among them: Public sector spending is growing faster than Ukraine’s recovering economy and still accounts for more than 40 percent of a gross domestic product that will not exceed $100 billion in 2018.

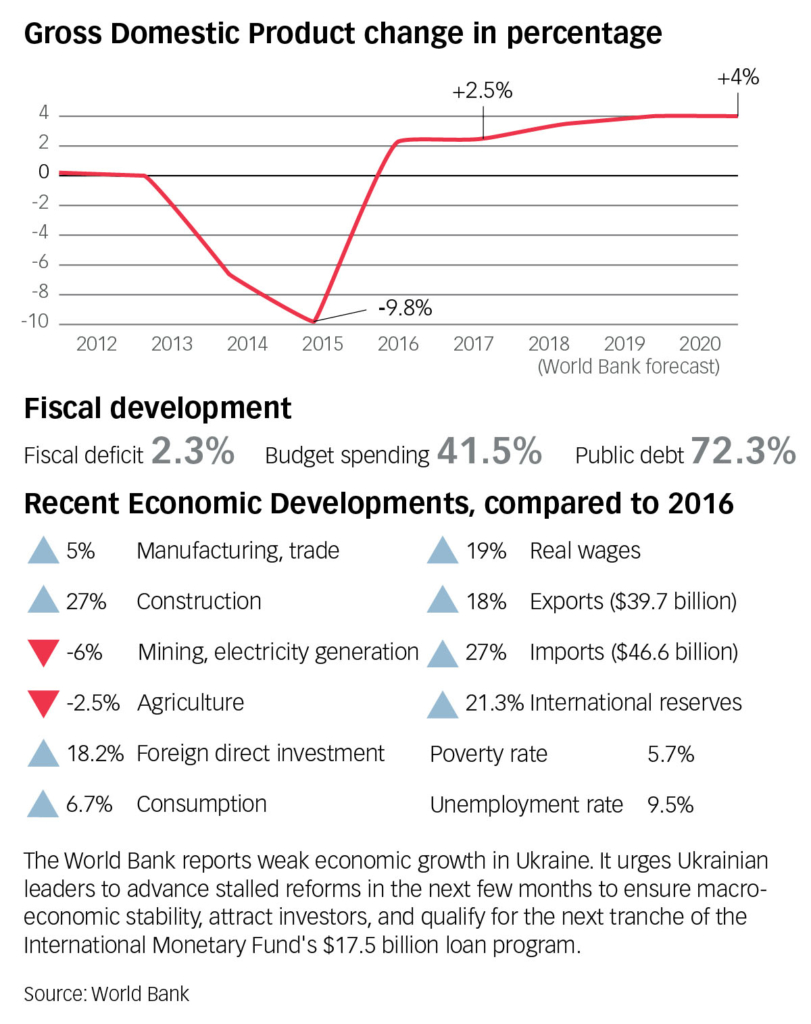

Additionally, stalled reforms threaten economic growth, which could amount to only 2 percent this year. The World Bank said Ukraine should strive to double growth to 4 percent and keep its fiscal deficit below 3 percent.

The nation will need to borrow an additional $18 billion in the next two years — including $8 billion from external sources.

Ukraine can only improve its economy by fighting corruption (including through the creation of an anti-corruption court), privatizing state enterprises, creating an agricultural land market and restoring trust in the financial sector.

Doing so is Ukraine’s only chance to restart low-interest lending from the International Monetary Fund, which hasn’t lent the nation any money in more than a year — disbursing only about half of a four-year program of $17.5 billion set to expire at the end of March 2019.

Weak rebound

Ukraine lost half of its $180 billion gross domestic product through currency devaluation and recession in the wake of the 2014 EuroMaidan Revolution, which saw former President Viktor Yanukovych abandon office and flee the country. The Kremlin’s military invasion and annexation of Crimea and war in the eastern Donbas soon followed.

Ukraine has never really recovered since then, only finally moving out of recession in the last two years — and barely — with just 2–3 percent GDP growth.

Foreign direct investment remains low, at 2.1 percent of GDP, “suggesting that improvements in investor confidence may be tapering off,” the World Bank said.

Fiscal burden

Public spending changes in assistance payments, education and healthcare were positive, but increased pressure on the state budget. Pensions for retirees and the salaries of teachers and doctors were raised while the minimum wage doubled. The upshot is that 41.5 percent of the nation’s economic output is spent in the public sector.

According to the World Bank, spending on wages and public services will hit 18.7 percent in 2018; wages and pensions are expected to rise also during the 2019 presidential and parliamentary elections.

And even though the government managed to keep the fiscal deficit flat at 2.3 percent of GDP last year, thanks to strong tax revenues, it will be difficult to keep it below 3 percent over the next two years without financial aid, foreign investment, and economic growth, the World Bank said.

IMF loan

Ukraine spends 4.9 percent of its GDP on household utilities subsidies. Natural gas distribution remains heavily subsidized, but the idea of raising gas tariffs for households to market levels is highly unpopular.

Gösta Ljungman, the IMF resident representative for Ukraine, said competitive market prices of gas for households would give incentives to companies and investors to produce more.

“Increase gas tariffs for households and then identify those who need subsidies,” Ljungman said on April 11 at the U.S.-Ukraine Business Council. “60 percent of customers already qualify for state subsidies, so the gas price increase won’t affect them.”

The IMF also wants Ukrainian government to reduce its public sector spending by selling off or closing more than 3,000 state companies. This year the State Property Fund plans to sell 700 state companies and hopes to raise $865 million (Hr 22.5 billion).

The IMF wants a law creating an anti-corruption court, privatization of state enterprises and market prices for natural gas as minimum conditions before lending another $1.9 billion tranche to Ukraine.

“Ukraine set up the National Anti- Corruption Bureau and the State Bureau for Investigations, but that’s not enough,” Ljungman said. “The existing courts are not ready to take on high-profile corruption cases — that’s why we need an anti-corruption court.”

The long delayed draft bill to form an anti-corruption court was submitted in December by President Petro Poroshenko, who reversed his opposition to the court in October under international pressure. It passed an initial reading in parliament in March, but remains bogged down by competing interests and obstructionist lawmakers.