NEW YORK — The Ukrainian Museum in New York is staging three distinct exhibitions, each with its own gripping theme but drawn together by tragic depictions of hideous acts perpetrated by totalitarian regimes from the last century to the present.

The museum in the heart of the New York’s Lower East Side, “Ukrainian Village,” is displaying exhibitions on the Holodomor, when 4 million Ukrainians were starved to death on orders from Josef Stalin in 1932-1933; the Holocaust, much of which was carried out by the Nazis against Ukraine’s Jewish population during World War II; the 1944 Soviet deportation of Crimean Tatars from their homeland and the ongoing Russian war against Ukraine.

The best-known Ukrainian artist exhibited at the museum is Mikhail Turovsky, who emigrated to New York in 1979. Sixty of his large, vibrantly-colored canvases painted with bold brushstrokes applied in thick layers are on display.

Turovsky was born into a Jewish family in Kyiv in 1933. They avoided becoming victims of the Holocaust because they were evacuated to Uzbekistan, returning to Soviet Ukraine after the war.

He studied at the Kyiv Art Institute and, as a young artist in the 1960s, mixed with other artists, writers, and dissidents who, if not exactly rebelling against the communist system, challenged it and were known as the “shistdesiatnyky,” or the people of the Sixties.

Many were jailed or otherwise persecuted, which eventually prompted Turovsky to take advantage of a U.S.-negotiated agreement permitting Jews, who were especially targeted by Soviet regime, to emigrate.

In New York, Turovsky created images reflecting his new home, but Ukrainian themes continued to figure in his paintings. Much of his work deals with the 20th century’s two largest atrocities carried out on a mind-numbing scale: the Holodomor and the Holocaust.

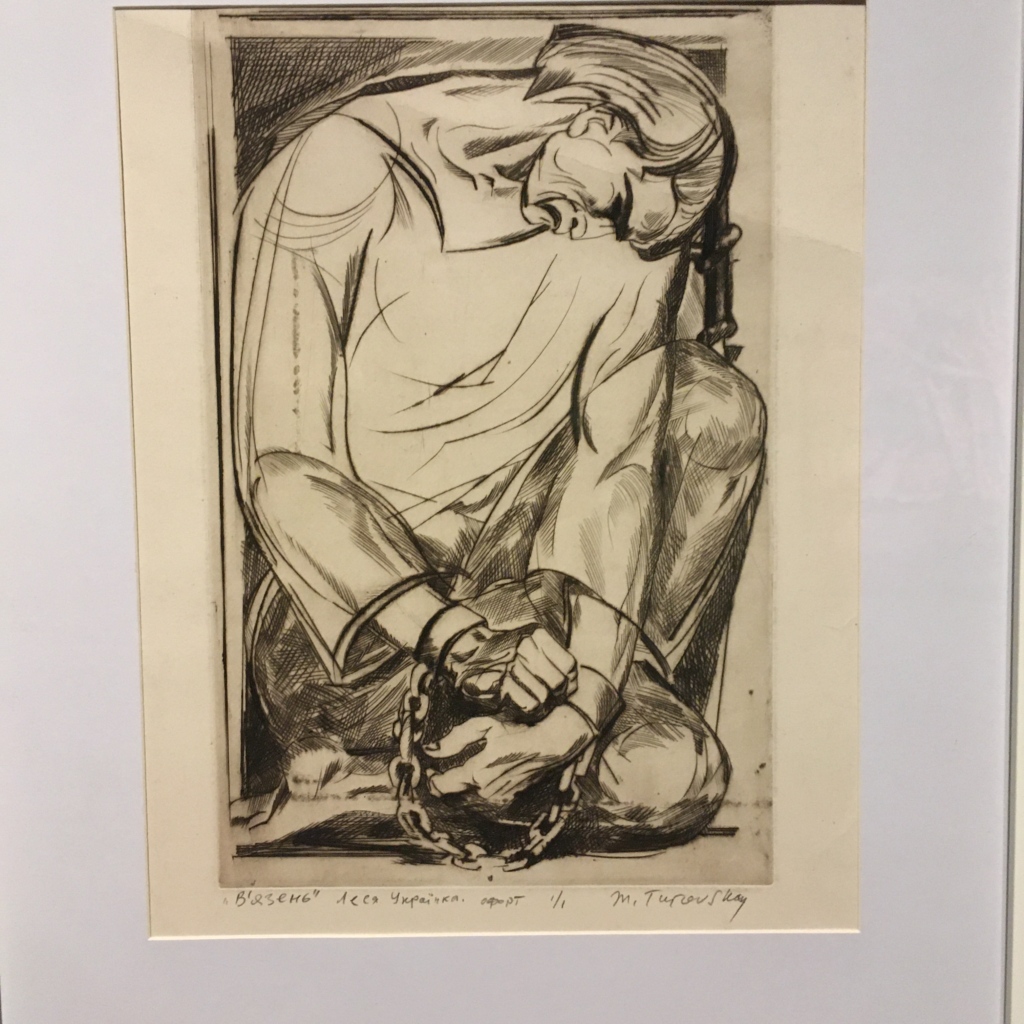

Other subjects include Ukrainian landscapes, American cityscapes and erotic female nudes. On display are also etchings from his early days created as illustrations for the work of 19th century Ukrainian writers Vasyl Stefanyk and Lesia Ukrainka.

An etching by Mikhail Turovsky to illustrate Lesia Ukraininka’s poem The Prisoner on display at the Ukrainian Museum in New York City. (Askold Krushelnycky)

Mothers with children are a recurrent theme in his work – some are peacefully reminiscent of the Virgin Mary and Christ, while, in others, the mother seems to be desperately trying to protect her child from an external threat.

Hanya Krill, the museum’s program director, said that Turovksy “appreciates and enjoys his connection with Ukraine. That’s his homeland. The whole family is very involved with Ukrainian culture. Their son Roman, who is an artist and musician, came to the opening of the exhibition in a vyshyvanka sorochka (traditional Ukrainian embroidered shirt) and performs very often with Julian Kytasty, a prominent exponent of that most Ukrainian instrument, the bandura.”

Turovsky has become widely known in America and his work has featured in exhibitions around the world, with his paintings selling for between $20,000 and $30,000.

Mother and Child by Mikhail Turovsky on display at the Ukrainian Museum in New York City.

Another exhibition at the museum features photographic portraits by Zarema Yaliboylu, born in 1986 into a Crimean Tatar family, which trace the dreadful story of the deportation of Crimean Tatars, carried out in 1944 as collective punishment for those who fought against the Soviet’s during World War II.

Over two days in May 1944, Soviet secret police went from door to door, giving Crimean Tatars some 20 minutes to gather their belongings. Men, women and children were then crammed into cattle wagons that rumbled slowly across the Soviet Union in freezing, unsanitary conditions for 10 days if they were lucky or several weeks if they weren’t.

Their destinations were the Urals and Central Asia, where those who survived the journey were disgorged into barren areas and forced to work as cheap labor in factories, mining, harvesting cotton and building roads. Most were left with minimal tools and materials to try to build shelters from the harsh winter cold and given little food.

Thousands of some 180,000 deportees did not survive the winter, dying from hunger, typhus, cold, lack of oxygen in the stifling wagons and sheer exhaustion. Researchers estimate that up to 40% of those deported died during transport or within five years of being exiled.

In the late 1980s, some of the deportees or their children started to drift back illegally to their homeland, and the flow increased after Ukraine became independent in 1991 and allowed Crimean Tatars to return to the peninsula.

Over the last eight years, Yaliboylu has created a film archive showing old Crimean Tatar houses, though some of her most powerful works are portraits of elderly Crimean Tatars who were deported as children and returned as adults, mostly in the 1990s, with faces deeply etched by lifetimes of oppression.

More recent events on the Ukrainian peninsula, now occupied by Russia, have imbued the images with the quality of a recurring nightmare. Now many of those who survived Russian deportation in their childhoods are once again living in fear of Russian occupiers.

Yaliboylu left the peninsula after the Russian invasion, but returned for two weeks this March, and some of the photos she took during that stay are in the exhibition.

Other artifacts, such as Crimean Tatar textiles, ceramics and images, provide an atmospheric backdrop to the compelling photographs.

Ukrainian artist Vlodko Kaufman, born in Kazazkhstan in 1957, brings Ukraine’s recent history, molded by Russia’s 2014 invasion and the subsequent war, into searing focus with a multitude of images representing Ukrainian soldiers who have died defending their homeland.

Kaufman studied in Lviv and is regarded as an important influence in the development of Ukrainian art since independence as a member of the artistic society “Shliakh” (the path) and a co-founder and Artistic Director of the Dzyga Art Association in Lviv.

As the war unfolded, Kaufman began creating images to pay homage to the dead, using pens, pencils, crayons, markers and brushes on any canvas that came to hand – restaurant receipts, train tickets and scraps of paper.

Krill, the program director, said: “He started making these when the first reports of the dead came in. As he heard more reports, he would draw that many more portraits. There are more than 10,000 portraits, and many of them are mounted here. He has vowed to continue to expand this collection of portraits until the war ends.”

Vlodko Kaufman’s haunting images of soldiers killed in the ongoing Russian-backed war in eastern Ukraine are currently on display at the Ukrainian Museum in New York City. (Courtesy of the Ukrainian Museum)

Rather like representations in monuments to the unknown soldier, the images do not come with a name or recognizable faces, as if passing from our world of the living to another.

Other features too are vague. Is that a proper military helmet worn by a soldier on the Donbas front lines or a construction worker’s protective headgear, as used by some of those killed during the EuroMaidan Revolution in 2014?

Yet human emotions jab out of them starkly, like caresses from a bayonet’s edge. The effect is both jarring and haunting as visitors enter a gallery where each wall is filled with hundreds of images, each different, representing men and women whose lives, ambitions and dreams have been snuffed out by the invader.

“This is an attempt to understand what is really going on” Kaufman said of the works. “This is a discussion, a conversation, a contemplation. The statistics are unemotional and cold: X died, Y were injured, Z were saved…They gradually appear every day, as does information about the dead, the wounded, and the missing.”

Museum program director Hanya Krill stands before Vlodko Kaufman’s works at the Ukrainian Museum in New York City. (Askold Krushelnycky)

Krill said that most of the museum’s visitors are not of Ukrainian origin. “We’re excited by that, because not only do we have as part of our mission this idea of preserving and presenting Ukrainian culture for the diaspora community but also to take it to the world.”

She said one aim of the current exhibitions is “to remind our public that the war is ongoing, it hasn’t ended. People aren’t talking about it as much, but Ukrainians are still dying five years later.”