Russian President Vladimir Putin is having a lucky streak.

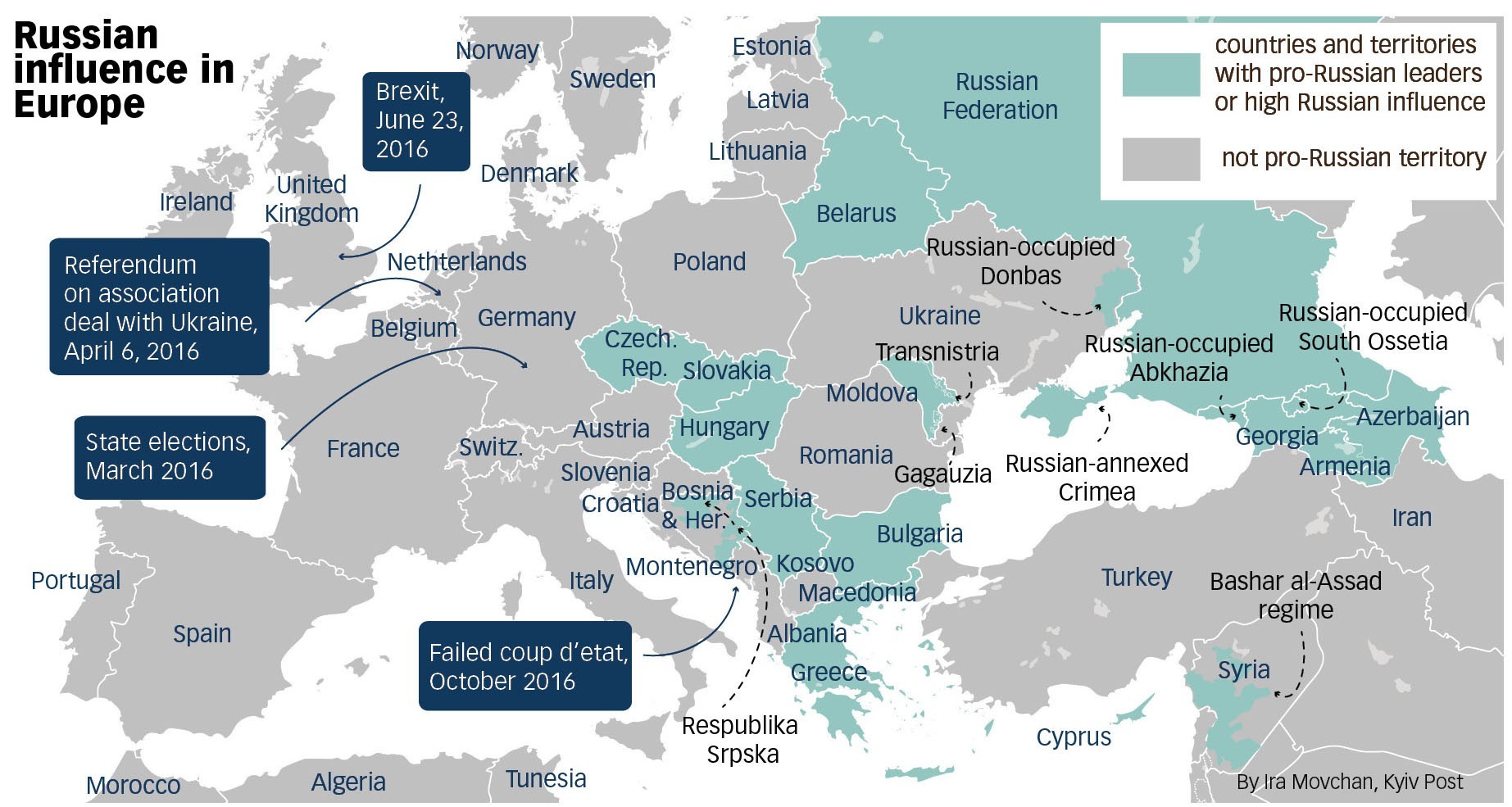

Donald Trump, who has flirted with the Kremlin and hinted he might accept its annexation of Crimea, won the Nov. 8 presidential election in the United States. Several days later, pro-Russian politicians were elected presidents of Moldova and Bulgaria on Nov. 13.

It is not clear if Moldova and Bulgaria, which are parliamentary democracies, will drift towards the Kremlin, given the limited presidential powers in both countries and their dependency on Western support.

But the election results show that pro-Russian sentiment in European countries is strong.

A party vacillating between Russia and the West also defeated a staunchly pro-Western one in Georgia in October. And in the United Kingdom, a majority supported leaving the European Union at a referendum held in June – a move welcomed by Moscow.

Another event favorable to Russia was the Dutch referendum that rejected a political and trade association deal with Ukraine with 61 percent of the vote in April.

Masterfully using its oil revenues and propaganda machine, the Kremlin is spreading its influence in Europe and hoping for its supporters to come to power in Austria, Germany and France.

The Kremlin’s expansion may weaken the West’s support for Ukraine in its war with Russia and hurt Ukraine’s drive to integrate with the European Union.

Since the spring of 2016, a string of referendums, elections and other political events favorable to Russia have occurred in Europe. In the face of a revanchist Russia, many European states have seen pro-Russian political parties, from both the left and right spectrums, gain influence.

‘Russian’ victories

Moldovan Socialist Party leader Igor Dodon defeated pro-Western candidate Maia Sandu in the Nov. 13 presidential vote. He pledged to make his first presidential visit to Russia and gave his first interview after the victory to Russia 24, a Kremlin propaganda channel.

Dodon has called Crimea, a Ukrainian peninsula that Russia annexed in 2014, “de facto Russian” and promised to give broad autonomy to the Kremlin-backed breakaway republic of Transnistria, Moldova’s equivalent of Ukraine’s Donbas breakaway “republics.”

Sergiy Gerasymchuk, a Moldova expert at Ukraine’s Strategic and Security Studies Group, thinks that Moldovans backed a pro-Russian candidate in protest against the pro-Western government’s corruption.

Gerasymchuk added that Dodon would have to change his anti-Western rhetoric, since Moldova is heavily dependent on Western aid. The country, however, is also dependent on the Kremlin, with Russian gas giant Gazprom controlling Moldova’s gas pipeline network.

In Bulgaria, the Nov. 13 presidential election was won by Rumen Radev, who is known for his pro-Moscow and anti-immigrant rhetoric. In the wake of Radev’s election, the country’s pro-European Prime Minister Boyko Borisov resigned.

Bulgarian journalist Krassimir Yankov attributed Radev’s win to the people’s disappointment with corruption scandals associated with the pro-EU government. Yankov also doubts that Radev, a former NATO fighter pilot, will pursue an openly pro-Russian policy.

“He’s not against membership of NATO and the EU, but he insists on improving dialogue with Russia,” Yankov said.

Yankov added the Bulgarian society was equally divided between pro-Russian and pro-Western moods. Russia is still seen by many in this county as the liberator from the Ottoman Empire, and the pro-Russian Orthodox church is influential.

The Kremlin is also boosting its clout in Georgia. The ruling Georgian Dream Party won 77 percent of the seats in the Oct. 30 parliamentary election – a constitutional majority, while the pro-Russian Patriotic Alliance got 4 percent of the seats.

The Georgian Dream has combined pro-Western rhetoric with a promise of better relations with the Kremlin. The Georgian Dream government has stepped up economic cooperation with Russia, while the Kremlin’s media presence in the country has soared.

Others under influence

Other countries in Europe are also subject to Russian influence.

Slovakia now has a partially pro-Russian cabinet and an openly Kremlin-friendly prime minister, Robert Fico, according to Olexia Besarab, a Slovakia-based expert at the Strategy XXI think-tank. She added that Russian businesses were very active in the country.

The pro-Russian sentiment is fueled by nostalgia for the Soviet Union.

“In the Soviet period, the defense sector was well-developed in Slovakia, people were making good money there,” Besarab said.

Russia is also sponsoring pro-Russian non-governmental organizations in Slovakia, Besarab said.

The British think tank Chatham House estimated in 2015 that the Russian-funded non-governmental organization sector in Europe is worth $100 million a year.

Meanwhile, Poland’s incumbent nationalist government, which came to power in 2015, has made some anti-Kremlin moves but at the same time taken an anti-Ukrainian stance in what some see as a policy encouraged by the Kremlin.

Specifically, in July the Polish parliament declared the 1943-1944 killing of Poles by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army in Volyn to be genocide, while ignoring the similar killing of Ukrainians by Poles.

Serbia and Montenegro are another area of interest for Moscow, as both are Orthodox countries with historical ties to Russia.

In October, the Montenegrin authorities said that two Russian nationalists were behind an alleged plot to overthrow the national government and arrested pro-Kremlin Serbian citizens who had previously fought against Ukraine in the Donbas.

Republika Srpska, a de facto independent Serb enclave in Bosnia and Herzegovina, is also backed by the Kremlin.

Other pro-Russian leaders in Europe include Czech President Miklos Zeman, who has effectively recognized Russia’s annexation of Crimea and Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban.

Russia also has influence in the Orthodox Christian countries of Cyprus, an offshore haven for Russian businesses, and Greece, whose Prime Minister Alexis Tripras favors closer ties with the Kremlin.

Another tool of influence is the Soviet Jewish diaspora in Israel. Its Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu met with Russian President Vladimir Putin four times in 2016 only.

Coming elections

The upcoming elections in Europe may also increase Russia’s clout.

In Austria, pro-Russian politician Norbert Hofer of the far-right Freedom Party is among the leaders of the polls and has a chance to become president in the Dec. 4 election.

In France, Marine le Pen from the pro-Kremlin National Front is likely to win the first round of the April 23, 2017 presidential vote but may lose in the second round, according to recent polls.

Meanwhile, the Kremlin-friendly far-right Alternative for Germany is hoping to succeed in the country’s 2017 parliamentary election following its strong showing in state elections last March.

Destabilization tactics

Some analysts say the recent victories of pro-Russian politicians shouldn’t be overestimated because they were caused by corruption scandals rather than Russian propaganda.

“Such swings are normal, in democracies. There were somewhat similar fears in East-Central Europe in the 1990s when former communists returned to power,” German political analyst Andreas Umland told the Kyiv Post. “Russia is becoming economically and politically weaker. It can offer less and less to these countries.”

The Atlantic Council, a U.S. think-tank, said in a November report that “in Western countries, the Russian government cannot rely on a large and highly concentrated Russian-speaking minority as its target of influence and lacks the same historical or cultural links.”

However, the report goes on to say that “in this context, the Kremlin’s destabilization tactics have been more subtle and focused on: first, building political alliances with ideologically friendly political groups and individuals, and second, establishing pro-Russian organizations in civil society, which help to legitimate and diffuse the regime’s point of view.”

Gerasymchuk expects more pro-Russian politicians to come to power in Europe.

“Russian propaganda, funded with oil money, and the Kremlin’s efforts to base its foreign policy on expansionism, are doing their job,” he said.