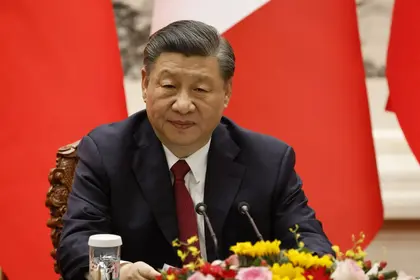

Especially in the context of the ongoing war between Russia and Ukraine, China’s leader Xi Jinping and his foreign policy remain a major focus of world attention, with new information emerging practically every week.

The latest was the visit to China by French President Emmanuel Macron and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, preceded by Xi's high-profile visit to Moscow. Macron tried to talk the Chinese leader into action for restoring peace in Ukraine. But as soon as the French president returned to Paris, Beijing launched a large-scale military exercise near Taiwan for the declared purpose of “working out joint actions for a comprehensive blockade of the island.”

Questions arose again: What is Xi after? What is China up to? Does China want peace - or is it ready to start a global military-political confrontation with the US and the West?

We can hardly get correct and logical answers if we only analyze China’s moves separately, especially hearing different and even opposite assessments of them. Some pundits talk about China’s real and rational desire for peace. Others are convinced that Beijing will continue to help Moscow wage war against Ukraine, saying China is ready for an escalation in its confrontation with Washington.

To my mind, China’s moves in the international arena should be assessed comprehensively, considering all their aspects and diversity. That would give us better insight into China’s current foreign policy.

South Korea Demands 'Immediate Withdrawal' of North Korean Troops in Russia

To describe Beijing’s international activity, I would use the term “multi-vectoral.”

Almost forgotten now, it was used during Leonid Kuchma's presidency (1994 to 2005) to describe Ukraine’s foreign policy, which at the time performed an adaptive function and served to maintain an optimal balance of the young country’s interests in relation to both Russia and the West. It was a policy of dynamic maneuver between the two centers of power on which Ukraine was equally dependent.

That “multi-vectoral” policy was supposed to secure the country’s internal and external stability. In the 1990s and early 2000s it worked. But when Viktor Yanukovych tried to pursue a similar policy during his presidency (2010 to 2014), he failed. He had to make a choice between two directly opposite vectors – European and Eurasian. It ended up a complete fiasco – and he fled to Russia.

However, China’s “multi-vectoral” foreign policy is entirely different from Ukraine’s in character and content. China is openly striving for global leadership and has an ambition to act as an alternative (to the U.S.) center of influence in international relations. Beijing even states its readiness to defend its interests militarily, but it’s not ready yet for direct, full-scale military-political confrontation with Washington and the West. That would inevitably provoke fragmentation of the global economy, which could be very painful economically since Western countries account for nearly half of China’s foreign trade.

Xi Jinping is likely to lead China toward a bipolar world, where it wishes to be one of the centers of influence counterbalancing the US, if unhindered by domestic or international issues. But in the transition period, while strengthening its global leadership and reducing its economic and technological dependence on the West, China is likely to pursue a flexible multi-vectoral policy.

What shows China's multi-vectoral foreign policy?

It’s a combination of global rivalry with the United States and differentiated relations with certain Western countries and leaders. This political line was clearly visible during Macron and von der Leyen's visit to China. While the French President got the red-carpet treatment, the European Commission President almost got the cold shoulder. Quite probably, Beijing might also try to disunite the West by playing on policy differences - especially on issues of Taiwan’s future status and relations with China.

China claims the role of defender of the interests of the global South in relations with the rich nations of the North. Russia seems to have the same ambition, but China has more financial resources and political opportunities.

China is combining its gradual political and economic expansion (through One Belt One Road, Shanghai Cooperation Organization, etc.) with the role of a peacemaker and go-between in settling burning or smoldering regional conflicts (e.g., between Iran and Saudi Arabia), but without direct or overburdening commitments.

If a conflict is burning and unlikely to end soon (as between Russia and Ukraine), China will hardly rush in. The role of a peacemaker and go-between allows China to establish its presence gradually, inconspicuously, but consistently in regions that have not been viewed within the sphere of its political interests before.

A part of China's policy is the gradual formation of a multilevel anti-US coalition - the axis and engine being the political and ideological enemies of the United States (Russia, Iran, North Korea). China may not necessarily be their formal leader but might act as their advocate and mediator. Occasionally, situationally and indirectly, this coalition could be joined by countries getting into disputes with the United States or other Western countries (e.g., some Asian, African and Latin American countries, or Saudi Arabia). There, China could play both ends against the middle.

Anti-Americanism is likely to be the political and ideological core of China's foreign policy.

This means that China will be neither on Ukraine's side (since Beijing views Kyiv as Washington's ally) nor an equidistant mediator in Ukraine peace talks, should they take place. Even if China joined Ukraine peace efforts, it would rather act as Russia’s “second” and its negotiating position would be based on its Taiwan interest. China may not recognize the Russian annexation of Ukrainian territories but will support their complete de-occupation only if the West recognizes Taiwan's reintegration into the PRC.

Regarding Moscow, Beijing’s interests consist in using Russia as an instrument and resource in the global confrontation with the US while increasing the Kremlin's economic and political dependence on China resulting from defeats on the Ukrainian battlefield. Therefore, China is not interested in Russia's complete defeat (which would strengthen the US) but will hardly provide the Kremlin with direct and massive support (which could provoke premature political and economic confrontation with the West).

And finally, Beijing's foreign policy rhetoric is not its actual foreign policy, which is substantially different. This concerns not only its relations with Russia (which was explained very well by China's ambassador to the EU), but also its relations with other countries.

We should take China's foreign policy realistically - without illusions or emotions. Under the current circumstances, China will not become our friend, but we should not take it as an enemy either.

We need a constructive dialog with China - but peace in Ukraine can only be achieved by militarily defeating Russia.

The views expressed in this opinion article are the author’s and not necessarily those of Kyiv Post.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter