The key to winning the Second World War was steel and aluminum, needed to build warships, airplanes, and weapons. The Cold War was a race to make atomic weapons from uranium, and today’s “war” is about semiconductor chips, small flat pieces of silicon with hundreds or billions of electronic circuits etched onto them that power the world.

Chips were invented in 1959 in America, but now the “Chip 4” alliance represents 70 percent of the global market and includes the US, Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea. Dubbed the “new oil,” semiconductors drive satellites, missile systems, warships, smartphones, refrigerators, vehicles, and economies.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

China, the fifth biggest chip producer, had hoped to overtake the US one day technologically and economically, which is why it covets Taiwan where 92 percent of the world’s most advanced chips are produced. But Washington militarily guards East Asia, and in August the President and Congress passed the CHIPS and Science Act to impede China’s access to chips, economic growth, and technological progress. Now it’s war.

The CHIPS Act works in two ways: It allocates $280 billion to boost chip production, train workers, and conduct research and development in the US. But it also blocks the export of strategically important chips and manufacturing equipment to China. Chinese companies are banned from dealing with firms that rely on, or provide, US technology, and Americans are prohibited from providing expertise to China. Naturally, Beijing reacted fiercely to this and has placed pressure on South Korea and others to sell it advanced chips, but to no avail. It also officially lodged a trade dispute against the CHIPs Act with the World Trade Organization because it is protectionist. And China continues to openly threaten Japan and Taiwan through a combination of naval saber-rattling and rhetoric.

Ukraine's Future: The Path to Victory

This is geo-economic warfare but has become entwined with geopolitical maneuvers over Russia’s ongoing destruction of Ukraine. And each superpower has reconfigured its strategies and alliances: America now leads a gigantic Western alliance against Russia, which includes all “Chip 4” members; and China remains neutral, attempts to bring about peace, and scrambles to replace Russia with new allies and partners. Beijing recently forged a diplomatic arrangement with Saudi Arabia and Iran to insure future fossil fuel supplies as Putin’s regime craters, and China now actively courts Moscow’s five former Republics in Central Asia – Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan – where consumer markets and metals or minerals needed for future technologies await exploitation.

China’s desperation to obtain advanced chips (to develop its artificial intelligence and supercomputing industries) has resulted in clumsy and unusual tactics. Beijing, for instance, has threatened to hold South Korea and Japan’s China-based industries hostage unless chip technology is made available. By contrast, it initiated a charm offensive in the Netherlands where Dutch technology giant, ASML Holdings, holds a worldwide monopoly on the systems, or “machines,” that are essential to all mass production of chips. (ASML was launched in 1984 by electronics giant Philips and a small chip-machine manufacturer and is the world’s only maker of the complex lithography systems needed to produce cutting-edge chips.) Its website cheekily boasts that it is “the most important tech company you’ve never heard of” and it’s true. ASML employs 39,000, has revenues of EUR 21.2 billion, and currently controls access to computing power.

But the link between geo-economics and geopolitics was illustrated this month when China’s Vice President Han Zheng attempted to persuade the Dutch government to give ASML a license to sell its most advanced products to Chinese customers. He spent three days meeting with Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte, the Dutch King, and ASML executives to discuss trade, but the Dutch were only interested in the war against Ukraine and what China could do to help stop Russia’s aggression.

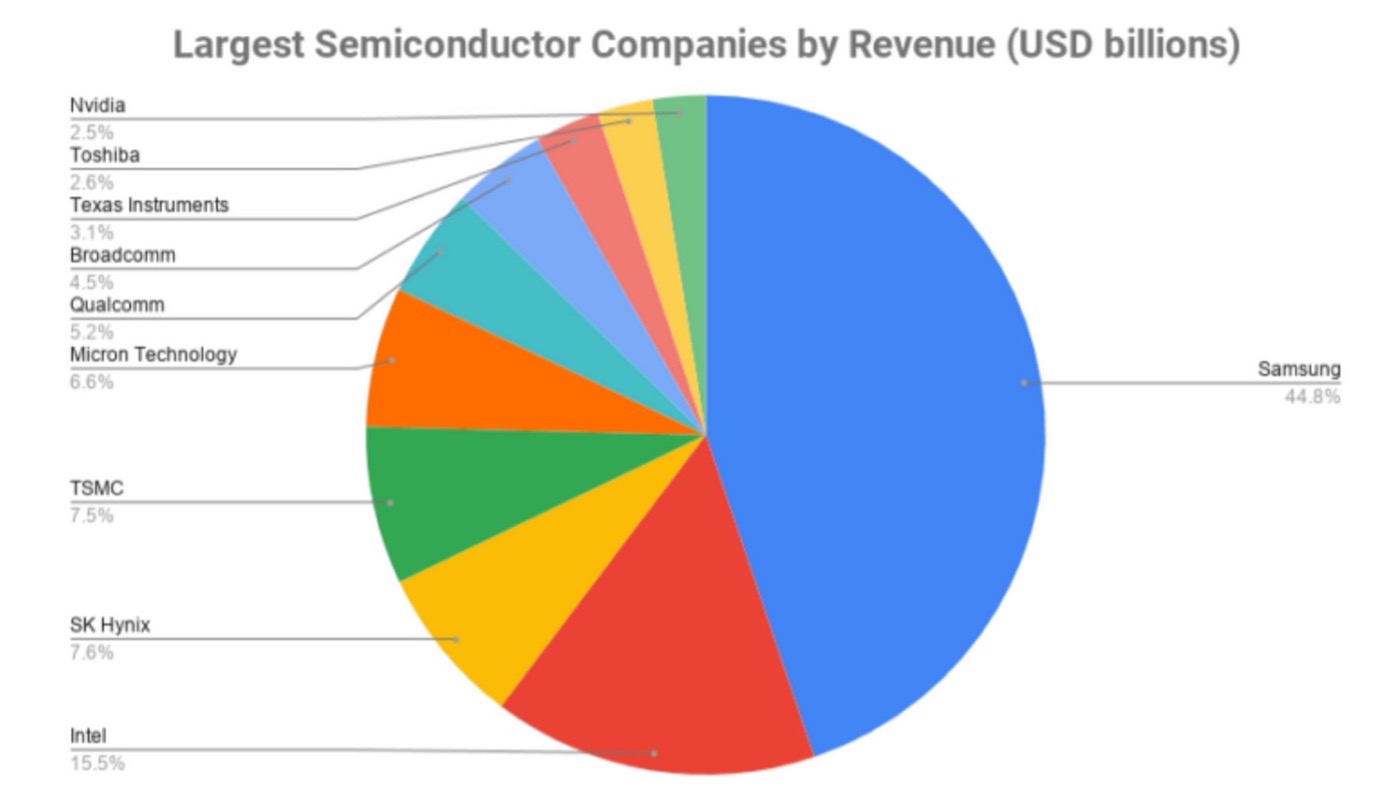

Highly concentrated sector as of 2022

China may be shut out of chips, but, on the other hand, it enjoys leverage over others because it has spent years gaining control over the supply chain of essential materials needed to electrify and transform societies in the future. According to a recent piece in The New York Times, China owns 28 percent of lithium mines, 41 percent of all cobalt mines and 73 percent of cobalt refineries; it makes 77 percent of cathodes and 92 percent of anodes needed in batteries; and China assembles most battery cells and makes most electric vehicles. The Times noted that “countries that can make batteries for electric cars will reap decades of economic and geopolitical advantages. Despite billions in Western investment, China is so far ahead – mining rare minerals, training engineers and building huge factories – that the rest of the world may take decades to catch up.”

Not surprisingly, the economically significant auto industry – centered in the US, Germany, Japan, and South Korea – has been scrambling to obtain access to these supplies as well as chips. The supply chain interruptions during the pandemic resulted in major production lines being shut down for long periods of time and major shortages in appliance stores for products reliant upon chips. Today, the same threat exists: America dominates the world of chips, but China dominates the materials of the future.

This “mutually assured destruction” is partially why, on April 20 US treasury Secretary Janet Yellen offered an olive branch to Beijing to work out their tech transfer differences. In a speech, she said “the world is big enough for both of us… A full separation of our economies would be disastrous for both countries. It would be destabilizing for the rest of the world… and [we] should work on areas of shared challenges for the two nations and the world.”

This was boilerplate, feel-good trade talk, but the underlying message was China was being offered a chips-for-Russia deal if it helped bring about peace in Europe. The quid pro quo was understood, and immediately recharged high-level talks between the two superpowers and juiced Beijing’s peace efforts in Europe to mollify America. Right after Yellen’s speech, President Xi Jinping called President Volodymyr Zelensky for the first time since the invasion to offer his personal sympathies and offer help in bringing about a solution. A possible detente over chips has been noticed and undermines Putin.

Naturally, China considers America’s “protectionist” gang-up as totally unfair and potentially suicidal. But it was in response to years’ worth of rampant trade cheating practices by China, intellectual property theft, accounting frauds concerning Chinese public companies listed on American exchanges, and massive subsidies to aggressive telecoms champion, Huawei Technologies, among others.

Now that both sides have plenty of what each one requires going forward, the detente may improve the global economy if scarce but essential commodities and products are accessible to all who trade fairly. However, in the future, geo-economic and geopolitical strategies must be in sync. That means China must dump Russia if it ever wants to prosper again and it must stop yammering on about invading peaceful, independent neighbors just because they have developed better, world beating technologies.

The views expressed in this opinion article are the author’s and not necessarily those of Kyiv Post

Reprinted from [email protected] - Diane Francis on America and the World See the original here.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter