Does the Kremlin really use psychological operations to sow chaos in America, or is that just the stuff of conspiracy theorists? Russia’s recent reaction to the crisis at the Texas border suggests the threat is real and growing. Rather than debate whether Russian efforts to inflame debates exist, it is time to flip the script and proactively apply Putin’s strategy to Russia itself.

Certainly, the immigration crisis is complex and decades in its formation. There is no magic formula. The southern border made headlines last month as Texas Governor Greg Abbott placed razor wire and other barriers at the 47-acre Shelby Park in Eagle Pass, along the banks of the Rio Grande that marks the border with Mexico. Abbott’s goal was to stem the flow of migrants crossing from Mexico and highlight Biden administration non-enforcement. President Biden then took the matter to the Supreme Court, which voted 5-4 to allow federal officers to remove the concertina wire.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

While proponents of open immigration celebrated the win, the ruling was nuanced. First, it was narrow and more of an emergency injunction. No briefs accompanied its release. That will come with rulings in several other cases now pending before the Supreme Court, including Texas Senate Bill 4 that bans sanctuary cities in the state. Second, while the court said the federal government could remove border obstacles, it did not prevent Abbott from re-installing them.

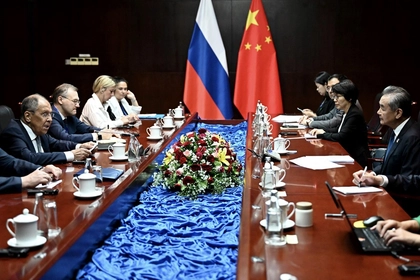

Russia, China FMs Meet as ASEAN Talks Get Underway in Laos

Put another way, the issue is fraught with both theater and debate, just the fertile ground upon which Russia’s psychological operations warriors thrive. The Russian take? Texas is about to secede and America will fall into civil war. Russian Foreign Ministry Spokeswoman Maria Zakharova, for example, joked that Biden should “form an international coalition” to free Texas; and Dmitry Medvedev, Russia’s former president and deputy chair of the Security Council, warned that Texas was on the verge of a “more destructive” civil war. Russian TV host Sergey Mardan rejoiced, likewise suggesting the Texas crisis would lead to “Civil War 2.0.” He explained: “If your enemy is facing a problem, you need to help turn it into a catastrophe.” Russian lawmaker Sergey Mironov offered to help Texas gain independence.

Enter social media. First Russians stated posting on X (formerly Twitter) and Telegram messages such as “Texas, we are with you! Freedom for Texas!” Posts with pictures “Texas People’s Republic” flags appeared, along with jokes about Putin signing a decree to recognize its independence.

It is an old playbook. Russia previously backed California secession and, in Europe, has supported Catalan and Scottish independence. It currently underwrites Republika Srpska, which seeks to secede from Bosnia. Putin realizes if he germinates the seed, a movement might sprout, even if they do not seek Putin’s support. Daniel Miller, president of the Texas Nationalist Movement, used the crisis to reiterate calls for Texas to leave the union, so-called “Texit.”

Much of Russia’s posturing actually reflects projection of its own problems. Perhaps Washington could then flip the script to exploit and exacerbate Putin’s worries about separatism in Russia. Putin fears ethnic minorities could form secessionist movements to fracture Russia itself. After all, the Russian Federation consists of 46 regions, 21 republics, 9 territories, and 1 autonomous region, many of which are, in theory, ethnically based. The country’s 160 ethnic groups speak 100 languages.

Putin is open about his concern. In 2011, he stated that if the North Caucasus Federal District were to leave Russia, the consequences would be devastating. Nikolai Patrushev, Russia’s Security Council secretary, accused the West of seeking to stoke separatism in Karelia, along the Finnish border. Sergey Naryshkin, head of Russia’s foreign intelligence service, also claimed the West supports “separatist terrorist structures calling for subversion of the Russian state.”

The paranoia is rooted in reality. The Chechen Wars from 1994-1996 and 1999-2009 were real. Groups such as the Buryats, the Yakuts, and the Chechens resent discrimination and disproportionately high casualty rates in the Russian military. After Russia stripped the Autonomous Republic of Tatarstan presidency from Rustam Minnikhanov, Washington could encourage every Tatar in Russia to fight for their rights.

Perhaps no separatism would germinate, or maybe some would. Regardless, the best deterrence to Russian interference is not hand-wringing, but recognizing that Russian strategy reflects its own weakness. To force Putin to invest time, energy, and resources into defense rather than on the United States and Ukraine would be a win-win. Putin must understand: Two can play at his game.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter