Since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine Feb. 24, 2022 we have been witnessing a steady, strong stream of international productions or readings of Ukrainian plays.

Sasha Denisova’s My Mama and the Full-Scale Invasion, Philadelphia, January-February 2024, and Natalya Vorozhbit’s Bad Roads, Toronto, November 2023, are two examples.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

As Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky recently reminded us, such undertakings are crucial to keeping the flame of Ukrainian culture burning, against the threat of being extinguished by Putin’s increasing use of old and new methods of Russification in his genocidal war against Ukraine.

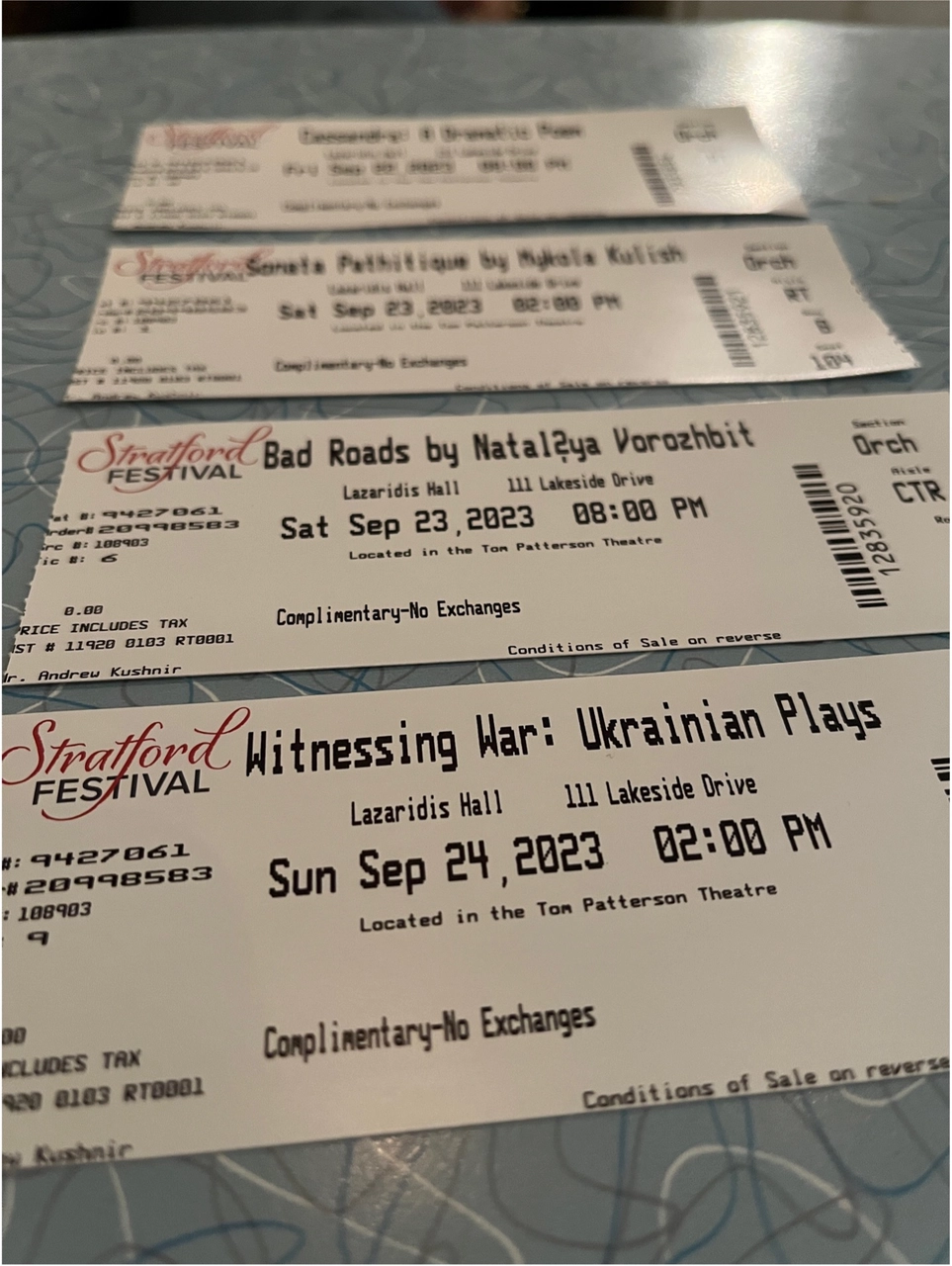

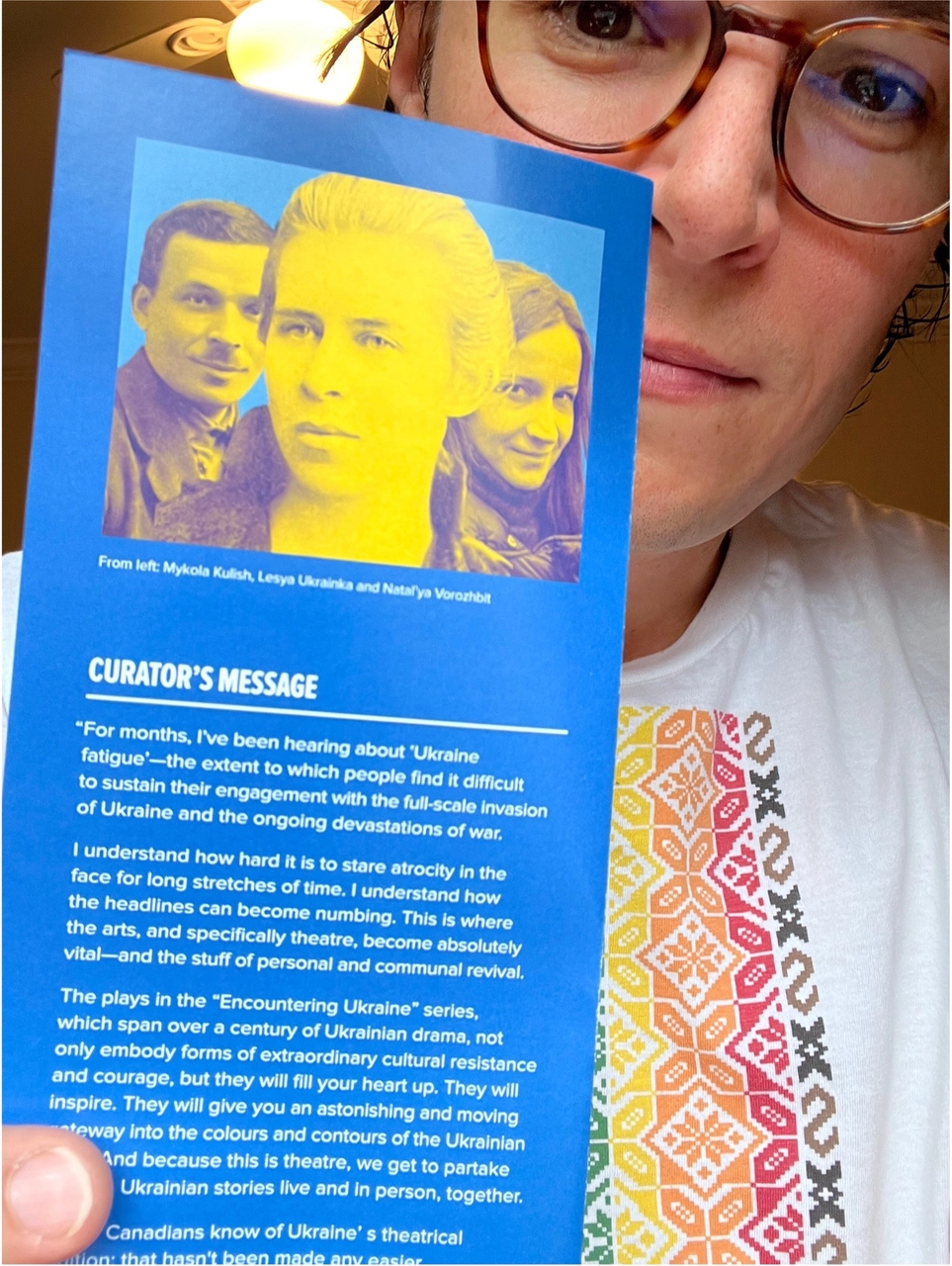

At Canada’s world-famous Stratford Festival, a unique, three-day cultural event took place last fall. Titled “Encountering Ukraine: Readings in Solidarity,” curated and directed by Ukrainian-Canadian Andrew Kushnir, it powerfully illustrated President Zelensky’s point and, frankly, has surpassed in scope and significance all projects in Ukrainian theatre outside Ukraine before and since.

The main theme of “Encountering Ukraine” was Ukrainian theatre and its contribution to the growth of an autonomous Ukrainian national culture in times of peace and war. The program consisted chiefly of readings (in English) of ten Ukrainian plays: two classics and eight contemporary works.

The one important exception to the “readings” format was the Saturday-morning panel. The main topic was eloquently stated in its title, “Stepping Out of the Shadow: Ukraine Known on Its Own Terms.”

Mikhail Reva: Stirring the Soul – With Shrapnel Transformed Into Art

Of particular interest was panelist CIUS Press Director Dr. Marko Stech’s hypothesis about Fyodor Dostoevsky. Dostoevsky’s novels are widely thought to express an anti-Western, Christian Orthodox, ultra-Russian-nationalist outlook. They nonetheless contain Western spiritual ideas that, Stech argues, bespeak a strong Ukrainian influence traceable to his father’s upbringing – Dostoevsky’s paternal grandfather was a Ukrainian Uniate Church priest – which informed his own sensibility. This would be an example of how Ukrainian culture helped shape “Great Russian” culture. Stech voiced similar thoughts about other “Great Russian” cultural icons, including novelist Nikolai Gogol and avant-garde artist Kasimir Malevich.

Tragic parallels: ancient and modern

Friday evening’s main feature was a reading of Lesia Ukrainka’s Cassandra. Set in Homer’s Troy in the Trojan War’s last days, the play can be interpreted as a historical allegory of an aspiring Ukrainian nation-state in its fraught relationship with Russia, the former roughly symbolized by Troy, the latter by the conquering Greeks. Political-philosophical themes such as the tensions between truth and the noble or useful lie, reason and revelation/prophecy, the common and the individual good, men and women, freedom and slavery – all are explored without being dogmatically resolved. In the play, true to Homer, Troy is ultimately defeated and erased.

The reading was preceded by the Festival Artistic Director Antoni Cimolino’s introductory remarks, wherein he brought up another parallel from ancient history, the Persian Wars as dramatized in Aeschylus’ tragedy. The setting is the palace of Persia’s King Xerxes at Sousa in the second Persian War. The Queen-mother is brought word of the Persians’ staggering defeat by the greatly outnumbered but incomparably valiant, freedom-loving and patriotic Greeks. The Persians are to the Greeks, Comilino suggested optimistically, as Putin’s Russians are to the Ukrainians: the Greeks emerge victorious.

The antique parallels with present-day Ukraine which Ukrainka and Cimolino have drawn from the Trojan and Persian Wars respectively, capture two possible, starkly opposed outcomes for Ukraine in its war of self-defense against Russia: either total erasure or complete victory. Which, we were left wondering, will it be?

Rare but irrepressible notes of hope break the monotony of the plays’ pervasive bleakness.

Saturday afternoon was taken up with Mykola Kulish’s Sonata Pathétique. Set in an unnamed provincial town in what is now Ukraine during the tumultuous years 1917-18, the plot unfolds the conflicts among the competing political forces rending the Ukrainian nation. The nationalist heroine, Maryna Stupai-Stupanenko, and her nationalist father, Ivan (aka Stupai), who contend against Bolsheviks, conservative Tsarists, Russian liberals, and other factions for an independent Ukraine, are finally defeated and killed – in her case tragically. The contemporary viewers of the 1930 play were compelled to ask whether along with their death died the dream of Ukrainian independence.

Maryna’s status as tragic heroine is underscored by a defining, Wagnerian characteristic of the drama. At various points in the play, she renders passages from Beethoven’s Sonata Pathétique on the piano, such that each passage conveys the main emotional substrate of the scenes linked to it – much as the orchestra, with its non-rational metaphysical wisdom, does for the action on stage of a Wagnerian music-drama.

Bad roads to Putinism

Saturday evening spotlighted Vorozhbit’s Bad Roads. This is a string of dramatically loosely related episodes bound together by their setting in Donetsk during the hybrid war instigated by Russia in eastern Ukraine’s Donbas region starting in 2014. In what’s perhaps the darkest episode, a young woman-journalist self-identifying as Ukrainian is held captive in a closed basement-room by a soldier, probably a Donbas separatist.

While he subjects her to brutal, degrading verbal, physical and sexual abuse, she tries to persuade him that he’s at bottom a good man and repeatedly declares her love for him. Eventually he relents. Moved by pity or her avowals of love, he gently washes her body and then kisses her tenderly. When he loses himself in a moment of trusting reverie, she quietly steps behind him and, grimly uttering, “I’m so scared of you,” smashes his head several times with a brick, then takes his gun and leaves. Shocked by the play’s ending, we yet come away with our sense of rough natural justice satisfied.

Another striking aspect of this episode is that Vorozhbit puts in the soldier’s mouth snatches of Putin’s propaganda about Western moral and cultural degradation from which noble Russia must be protected but to which Ukraine has unfortunately succumbed. As various commentators have noted, these and similar ideas are also being weaponized by authoritarian allies of Russia, such as China and Iran; the aim is to mobilize anti-Western states and factions in a new, increasingly militarized global “clash of civilizations,” wherein Ukraine figures as its first but not sole battlefield.

Putin’s propaganda murderously misapplies centuries-old, often profound lines of thought that probe the ethical and cultural failings of modern Western civilization. These lines run through the works of such 19th-century liberal thinkers as Alexis de Tocqueville, John Stuart Mill, and Matthew Arnold; and in the Russian empire, through Slavophiles, Eurasianists and other, often anti-Western, Orthodox-Christian writers, including Dostoevsky, Nikolai Berdyaev, and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. (Alas, the Russian line extends now to the philosophically controversial and morally execrable Aleksandr Dugin, who in 2014 ventured the option of genocidal war against Ukraine.)

Deceased prominent Western intellectuals and statesmen Vaclav Havel and Zbigniew Brzezinski, both politically left-of-center, have lamented the moral-spiritual impoverishment of the West’s liberal culture, which they claim people around the world deplore while lauding its freedom and prosperity.

The precise nature of these failings are matters over which reasonable people of different political persuasions can respectfully disagree and dispute. But Putin’s brutal, Duginesque bastardization of those ideas, as illustrated by the brainwashed soldier’s savage conduct towards his captive, serves only to discourage all such discussion in the liberal West. This, notwithstanding that Vorozhbit herself has the liberal-minded Ukrainian woman apparently concurring with her captor regarding family, religion, and the alleviation of poverty as marks of a good society.

Glimmers of hope

In setting the context for the readings of the contemporary Ukrainian plays, event-curator Kushnir made use of an analogy with Picasso’s Guernica to shed light on their mood. Given all the violence so graphically depicted in the painting, its mood could easily be felt to be one of unrelieved darkness and despair. Yet that would be a mistake, for in the painting one also finds a small but bright light shining onto the scene. That light represents a thin but irrepressible ray of hope amidst the ubiquitous carnage. And as in the Picasso painting, rare but irrepressible notes of hope, said Kushnir, break the monotony of the plays’ pervasive bleakness.

One such hopeful note is sounded in another episode of Bad Roads by the sense of moral responsibility that same young journalist woman acts on when, having accidentally run over their valuable, “golden goose” chicken, she tries sincerely to find a way to compensate its elderly owners, possibly at the risk of being financially exploited.

The seven contemporary, one-act plays read Sunday afternoon are all set in the phase of the war following the full-scale invasion.

Much like Bad Roads, these stories poignantly bring home to us what it’s like for Ukrainians, civilians as well as soldiers, to live through harrowing war-time experiences on or behind the front lines. We hear, for instance, of villagers outside on a starry night gazing up at the twinkling stars only to realize in horror that those are not stars but drones; and of a Moscow resident texting his Ukrainian niece: “I will come to you on a tank. You are fascists and Nazis. You must be destroyed.”

By putting on Encountering Ukraine, the Stratford Festival has set an example that other Western countries might emulate. If they do, their non-Ukrainian citizens will better understand and empathize with the imperiled nation. Those hitherto opposed to their governments’ support for Ukraine’s war of self-defense may thus soften in their opposition. Especially if they also learn to see that self-defense as part of the defense of the West against growing anti-Western aggression worldwide.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter