Goran Bregovic, a Serbian musician and composer, well-known globally for his Kalashnikov song, has been banned from performing in Moldova. This week, Bregovic was on his way to the Guitar Festival when the organizers of the festival announced on Facebook that he would not be able to perform. They cited “reasons beyond the control of festival organizers or artists,” and that the artist was stopped by Moldova's border police upon reaching Chisinau Airport.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

The Moldovan Interior Ministry, on Aug. 21 cited a ban on Bregovic because of his pro-Russian views as the reason for his and his band's denial of entry into Moldova over the weekend. Specifically, Moldovan Interior Minister Adrian Efros informed journalists that Bregovic supported Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014, which substantiated his pro-Moscow views.

In a statement from the Moldovan Border Police on Aug. 20, they asserted that based on the “risk analysis” and information exchanged with the Moldovan Intelligence and Security Service (SIS) and international partners, 29 foreign citizens aiming to enter the Republic of Moldova were denied entry within the previous 24 hours.

Moldovan Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Alaiba shared these suspicions, quoting on his social media that “to dance today to the music of Goran Bregovic is like dancing on the graves of all Ukrainians who died as a result of the armed conflict.”

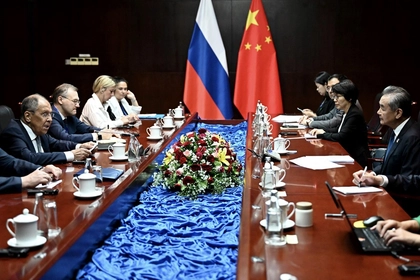

Russia, China FMs Meet as ASEAN Talks Get Underway in Laos

Bregovic seems to be confused why he was refused to perform in Moldova. He claimed, “I’ve toured with my musicians all over Europe many times and never had any difficulties anywhere.” This seems odd as he was previously banned from performing in Poland and Ukraine after performing in Crimea in 2015, leading the Ukrainian Foreign Ministry to state that he could “face up to a 15-day administrative arrest, fine or entry ban” for his actions.

Bregovic has a long history of maintaining a solidly pro-Russian viewpoint. In 2015, he declared that “the Balkan people have always felt Russia's grandeur,” adding that “I think the West has always been a little paranoid about this. I hope they will eventually get over it.”

This decision did not bode well for Belgrade. Serbia’s Foreign Ministry requested an explanation from Chisinau. Serbia’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Ivica Dacic, one of the leading pro-Russian voices in Serbian politics, who was awarded the Medal of Friendship from Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2018 for his dedication, asserted that “this decision does not correspond to traditional friendly relations between Serbia and Moldova.”

Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic downplayed Moldova’s concerns, insinuating that the country was overreacting in its concerns over Bregovic’s song “Kalashnikov” and mockingly expressed amazement that some countries could react to “such nonsense that comes from social media.” However, this ban has little to do with the Kalshnikov song.

Former Moldovan President and leader of the opposition Socialist Party, Igor Dodon, reacted with ire to the Bregovic's ban, claiming that Moldova’s President Maia Sandu, a staunch supporter of Moldova's future membership in NATO and the EU, was personally responsible for the ban. Sandu, who succeeded Dodon to the presidency, has been a recurring target of attacks by the former president who has regularly claimed that Sandu is overstepping her boundaries as president. Dodon, earlier this year, was released from home arrest for charges related to public corruption.

Tensions between Moldova and Serbia

This is not the first time that Moldova has banned Serbian citizens. This past February, Chisinau took the unusual move of blocking Serbian football fans from entering the country to attend a FC Sheriff of Tiraspol - FK Partizan of Belgrade match, which was announced by the Moldovan Football Federation within days of the game. At the time, Moldovan officials expressed concern that Russian-backed thugs, in the guise of being Serbian soccer fans coming to support the Transnistrian team, might have arrived in Chisinau with the intent of overthrowing the democratically elected government. President Sandu expressed that Montenegro, Belarus and Serbia were in cahoots in the plot to unseat her.

The Republic of Moldova, the poorest country in Europe, had been one of the few post-Soviet states to still cling to its Soviet past, having finally unseated the communist party during the 2009 elections. Since that time, Moldova has had a number of pro-European leaning parliamentary factions. A 2002[AJOS1] polling by the IRI found that 63 percent support Moldova's EU ascension, whereas 33 percent reject the idea. Of Moldova's nearly 4 million citizens, the IOM estimates that there were 1.16 million currently living abroad – predominantly in the EU.

As Moldova has drifted its geopolitical alignment closer to the West, Serbia has remained a staunch ally of Moscow by playing a delicate balancing game between Washington and Moscow. Due to Russia’s influence over operations in the region, combined with Belgrade’s reliance on Moscow’s energy, Belgrade has firmly placed itself in the Moscow camp, and has led efforts to extract financial support from the West in its bad faith effort to pursue EU membership.

Some in the West believe that Serbia is moving toward the West as it has also used its ostensible condemnation of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in the United Nations to present diplomatic consistency in framing the NATO intervention in former Yugoslavia as illegal and to protect Belgrade’s interests related to Kosovo. Furthermore, despite the diplomatic condemnation of the invasion, Serbia has refused to impose sanctions on Russia and has facilitated Russian sanction evasion by welcoming Russian businesses that enable such practices.

The West has consistently chosen a policy of accommodation towards Vucic’s regime in the hope of preventing him from siding with Moscow. This approach is misguided as the approach would only embolden both Vucic and, in turn, Putin both politically and financially. Given the history and geopolitical realities of the Russo-Serbian relations, Vucic has little logical reason to distance himself from Russia.

As is being seen now in Africa, Russia has sought to take advantage of its longstanding contacts to uplift its otherwise global setbacks. However, Moscow's inability to leverage its longstanding ties with Belgrade have shown that Europe is a different set of rules. Policy makers must remain consistent in assuring that those who have backed the Putin Regime know that there is no place for them in Moldova - or in Europe.

The views expressed are the author’s and not necessarily of Kyiv Post.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter