In this first article Kyiv Post examines the severity of the humanitarian and security threat Ukraine faces as a result of the extensive use of landmines and other munitions that followed the Russian 2022 invasion.

The extent of Ukraine’s Landmine and ERW problem

In his Dec. 8 address to the U.S. Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe, Michael Tirre, the Europe Program Manager for the U.S. State Department’s Office of Weapons Removal, said: “The humanitarian impact of landmines and unexploded ordnance was already severe in eastern Ukraine following the 2014 invasions and, tragically, this has been magnified exponentially by Russia’s [2022] full-scale invasion.”

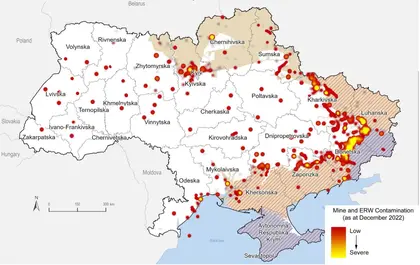

Tirre estimated that the area of Ukraine severely impacted by ERW was at least 160,000 square kilometers, an area the size of the United Kingdom; as the war continues, that figure increases daily. Until detailed surveys can be undertaken these estimates will remain simply that although, previous experience shows, that initial estimates can over-estimate the levels of contamination.

James Cowan, the CEO of the UK’s demining charity the HALO Trust, said in a February interview with the Canadian Journal Newswire, that the immensity of the affected territory, would require unprecedented funding and collaboration between donors, state and international demining organizations. His view, an echo of the situation at the end of World War II, is that it can only be “resolved by the creation of a 'Marshall plan for landmines', as a clear call to action for the international community."

EU Transfers €1.5 Bln Raised From Russian Assets for Ukraine

His view is supported by the Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor, which reported that the GLOBAL landmine clearance effort, measured against 35 active demining programs, had each year only managed to declare, on average, less than 1,500 square kilometers of “suspect” land as being clear and, within that figure, the actual area of landmines being removed was as low as 200 square kilometers. So, if the actual contaminated area in Ukraine is reduced by survey to half, about 80,000 square kilometers it would still take more than 50 years to clear the problem and then only if the equivalent of ALL of the clearance resources currently assigned to mine clearance globally were diverted to Ukraine.

What about the financial cost?

Landmine and Cluster Munitions Monitor report for 2022 reported a little under $600 million had been provided by 45 donors in 2021. It further estimated that a total of $12.7 billion had been provided to Mine Action in the period 1997-2021, of which a little under 70% was spent on mine and ERW clearance.

An article in the journal “Economics and Security” in 2006, by Bob French, estimated that the cost of demining varied from $2 to $39 per square meter depending on the country, terrain, climate, commercial and NGO involvement.

A report by UNMAS on demining programs in Afghanistan reported that the cost per square meter cleared had decreased from $3 in 1998 to below $1 in 2020. The reasons for this were not straightforward but factors such as 1998 “start-up costs” being amortized across the period, improvements in capacity and equipment enhanced efficiency, and an increased use of competitive bidding for specific clearance tasks. They now believe costs could be as low as $0.75 a square meter.

So, let’s be optimistic. Let’s assume that the actual area needing to be demined in Ukraine will “only” be around 80,000 square kilometers at a cost of “only” $0.75 a square meter. Then, at current levels of contamination, we come to a total of a minimum of 50 years to clear Ukraine at a cost of $60 billion.

The nature of Ukraine’s Landmine and ERW threat

Michael Tirre’s December speech further underlined that, it was the experience of deminers in Ukraine and elsewhere, that ERW represent as big, if not a bigger threat, than landmines. He said: “Russia’s munitions may have dud rates of between 10 and 30 percent, meaning massive amounts of unexploded ordnance will remain in the ground for years to come.”

The UN reported on Mar 3 that, since the Russian invasion, a total of 21,793 Ukrainian civilian casualties has been recorded in Ukraine, of which 8,173 were killed and 13,620 injured. These were as a direct result of artillery, missile and other attacks.

In a separate report Staista, the German on-line data site, reported that there had been total of 571 civilian casualties caused by mine-related incidents and the handling of explosive remnants of war (ERW), including 202 fatalities.

This latter threat to the civilian population will, as discussed, exist long after the war is over. We will look at what needs to be done in future articles.

What are explosive remnants of war (ERW)?

The Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) has compiled an “Explosive Ordnance Guide for Ukraine” which lists almost 150 types of landmines, rockets, missiles, artillery shells and grenades that have been reported by law enforcement, military, humanitarian organizations and civilians. GICHD readily admits that this “guide”, which was first produced in April 2022, is unlikely to provide a complete picture of what will be found, as new weapons seem to appear daily.

Illustrations of typical ERW munitions, which can come in all shapes and sizes, are pictured below. This is a very small sample, which helps to show the problems that all Ukrainians will face in the future as they pick up the pieces of their lives after the war is over.

Russian hand grenade.Photo: soldat.pro

Unexploded artillery shell.Photo: “dreamtime”

Unexploded artillery shell.Photo: “dreamtime”

Russian 120mm Mortar.Photo: iStock

Typical anti-tank missile.Photo: Unian

The PFM-1 APLPhoto : CAT UXO

Russian PMN anti-personnel mines.Photo: wikicommon

Russian anti-tank mines.Photo: wikicommon

The February “Newswire” article, reported that open-source satellite imagery shows minefields that stretch for hundreds of kilometers along the lines of contact between Ukrainian and Russian forces. While some of these are marked and recorded, in accordance with international convention, many are not and even where they are, over time fences and markers will disappear unless efforts are made to maintain them. As fighting continues and contact lines move, further mines are being laid, often with remotely-delivered, scattered, unmarked minefields. All of this will complicate the future identification and safe removal of these threats.

A Ukrainian civilian looks out over a marked mined area.Photo:UNOCHA Ukraine

A Ukrainian civilian looks out over a marked mined area.Photo:UNOCHA Ukraine

As if the physical and technical challenges posed by landmines and conventional munitions are not severe enough, there is evidence of the extensive, deliberate use by Russian forces of Improvised Explosive Devices (IED) and booby-traps, including children’s toys and even the bodies of people killed by the invasion. These devices are not only designed to kill and injury the Ukrainian military but are intended to inflict as many civilian casualties as possible and, thereby, make people afraid to return home.

Ukrainian servicemen prepare to check a body for booby traps in Bucha, April 2022.Photo:VOA News

Ukrainian servicemen prepare to check a body for booby traps in Bucha, April 2022.Photo:VOA News

Mobilizing the Response

For understandable reasons the Ukrainian authorities and the international community has focused on winning the war with little thought about what comes next. Those demining NGOs who have been active in Ukraine since the 2014 invasion have known for some time that, eventually, the war will end and rebuilding must begin. The level of the effort required is beginning to dawn on everyone, not least the Ukrainian Government.

The Communications Department of the Secretariat to the Cabinet of Ministers posted the following statement on 11 February 2023:

The problematic issues of humanitarian demining in Ukraine were discussed during a coordination meeting chaired by Prime Minister Denys Shmyhal and attended by the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Ministry of Defense, Ministry of Economy and the State Emergency Service.

"Due to the Russian aggression, Ukraine is currently one of the most mined and shell-polluted countries in the world. Humanitarian demining is the first stage in the restoration of the de-occupied territories, which makes it possible to start rebuilding housing and critical infrastructure. The need for demining is growing as the Ukrainian territories are liberated," the Prime Minister noted.

In future articles in this series, we will examine how Ukraine and the international community has responded to the landmine and ERW threat to date and identify the possible way ahead for dealing with this critical issue.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter