Christmas eve. A group of men huddle around a makeshift firepit, sausages slowly turning on sticks. Not far away, and evidently bitten by jack frost, the locals gather around a pastor, lowering their heads in prayer. It’s prayer of hope – hope for food, for clean water; to simply make it through the winter without freezing to death. But this isn’t Dickensian London. It’s 2022, and this is a village in southeast Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia region.

The Zaporizhzhia region has been a firm fixture in headlines across the world since the start of Russia’s illegal invasion in February, particularly the city of Enerhodar, which is home to the largest nuclear power plant in Europe.

On the first day of March, Ukrainian officials announced that Russian troops had surrounded the city, with Mayor Orlov reporting that residents were experiencing difficulties obtaining food and other essential supplies.

The following day, protestors blocked the roads into Enerhodar in an attempt to prevent Russian forces from entering. However, by the same evening, Rafael Grossi, Director General of the International Atomic Energy Agency, announced that Russian authorities had taken control of the territory around the nuclear power plant.

This was swiftly followed by a column of 10 Russian armored vehicles and two tanks approaching the plant, then capturing it after two hours of heavy fighting.

EU Transfers €1.5 Bln Raised From Russian Assets for Ukraine

Since then, the Zaporizhzhia region has experienced relentless Russian strikes and shelling, damaging local infrastructure and placing the nuclear power plant under grave risk.

Accompanying People’s Deputy Sviatoslav Yurash and his team of humanitarian volunteers, the wheels of the van we’re travelling in squelches over the rain-sodden mud as we roll to a stop in yet another Zaporizhzhian village on the front line.

Wrapped head to toe in thick warm clothing, the inhabitants are already outside waiting for us.

Like many people across Ukraine, particularly in the east, but also the south, these decent folks have been forced to endure the hardships of winter with additional problems brought about by Russia’s ongoing crimes against humanity.

The pastor leads a prayer with villagers amid shelling on the outskirts of Zaporizhzhia. Credit: Kyiv Post.

As a result of Putin’s targeting the energy infrastructure, they have been left without light, heat or running water for weeks, even months. But they aren’t moaning. In fact, they are displaying a mirror opposite attitude to what President Putin had hoped to inflict upon them – they’re defiant. United.

The pastor delivers his prayer while the sound of shelling explodes and vibrates in the near distance. The locals don’t flinch, now sadly accustomed to the noise of war.

After a unanimous “amen,” they form a line in front of the van, creating a human conveyor belt transferring crates of water and boxes of food and clothing to a large pile on the ground where it can be organized and distributed by the community leader.

Community leaders have proven themselves to be crucial components in helping civilians living in towns and villages like this one survive the ongoing war. Humanitarian groups such as the one Sviatoslav helps organize use them as vital points of contact, knowing that the important supplies they deliver will get to those who need it the most.

Photo credit: Kyiv Post.

Leaving the village, we drive through the dark, dodging potholes to get to our next stop, the city of Huliaipole.

Sviatoslav Yurash (center) with his team in Huliaipole, and Kyiv Post journalist Jay Beecher (far-right). Photo credit: Kyiv Post.

Almost every building here bears its own scars. Back doors riddled with bullet holes. Garden gates ripped to shreds by shrapnel. Collapsed roofs. Shell craters. A giant mound of rubble where a school once stood.

The majority of civilians have long been evacuated, leaving Huliaipole a ghost town of sorts.

Its history rich with stories of Cossacks and conflicts, the city is also the birthplace of Nestor Makhno, a Ukrainian anarchist revolutionary. Hailing from an impoverished family, Makhno went on to devote himself to the revolution of 1905, which saw mass political and social unrest aimed at the Russian Tsar and ruling class.

In February 1918, when representatives from the Ukrainian People’s Republic signed a peace treaty with the Central Powers (Austria-Hungary, the German and Ottoman Empires, and the kingdom of Bulgaria), Makhno formed a volunteer detachment to resist their occupation. Later he attained hero status among Ukrainians for his participation and leadership in the ensuing battles.

His gold-painted statue here is now partially covered in sandbags to protect it from yet another war that has reached his hometown.

“He was an extremely famous anarchist leader,” Sviatoslav Yurash says as he stands beside it. “He gained legendary status. Luckily for him he managed to survive the communist onslaught after World War I and went on to dictate his memoirs, so we have his vision.”

The statue of Nestor Makhno pokes up from a stack of torn sandbags. Credit: Kyiv Post.

A self-professed history buff, Yurash goes on to talk about legacies, and there’s a sense that he’s in the process of building his own.

Unlike many cardboard cut-out politicians, it was evident when I first met Yurash in May that he is a man of action, a figure who genuinely cares about his nation and its future.

His team, whom his friendly aide, Katarzyna Doroszowna, also helps organize, have worked tirelessly since February, often risking their lives to deliver supplies to the front lines.

Among them is Alexander Kuzniak, a warm patriot who, on the group’s last trip, helped deliver tons of humanitarian aid and medical equipment to the recently liberated city of Kherson.

With him is promising singer Aleksandar Levchenko, who says he comes from Donetsk in Ukraine’s east. When war broke out in 2014, Aleksandar sought safety in Kyiv, expecting to be able to return to his home city in just a month or two when things, in his words, “blew over.” But that was eight years ago.

Yurash’s group has seen many come and go over the months, each with their own story to tell.

Suddenly, an elderly man in a flat cap peddles his bicycle to a stop outside a nearby building. Ushering us over, he pulls out a set of keys and allows us inside for a brief tour. It is a local museum, heavily damaged by shelling, its artifacts relating to Makhno now resting behind smashed glass displays and, in some of the rooms, covered entirely by collapsed roof slates.

Yet another example of how Russia continues to attack and attempt to erase Ukraine’s history.

After unloading more boxes, this time to a group of people waiting patiently outside a hospital, we stop at one of the many army outposts. The group of soldiers there are wary of speaking to journalists, concerned that their location might be revealed. As a thank you for the supplies, a soldier hands over a “present” to one of the volunteers – a backpack taken from a captured Russian.

More stops follow. A couple of soldiers outside a catholic church in the middle of nowhere. A community hall in a neighboring village. The humble wooden home of a village community leader, the boxes from our van being stacked up by bench where a flock of hens have decided to take a rest, a rooster perched proudly in the lowest branch of the nearby tree.

Photo credit: Kyiv Post.

It's pitch-black outside by the time we get back to the pastor’s protestant church, where we’re warmly greeted by his wife in an adjacent kitchen. Supper is served up – a generous dish of meatballs and mash, cheeses, meats, coffee, and a selection of chocolates.

I’m then given a brief tour of the church itself, noticing as I walk around that people are constantly coming and going, collecting food or other necessities.

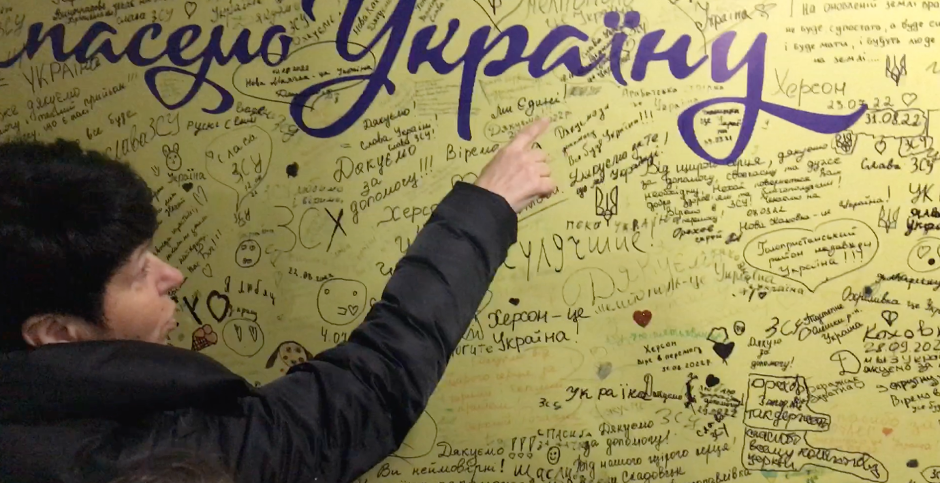

In a small cozy outbuilding, a small wood stove stands amid a row of beds. It’s in this room that I’m told 3,000 people, mostly refugees from the east of Ukraine, have so far been helped by the ministry. The wall is adorned with their gratitude, a huge poster containing hundreds of thank you messages from men, women, and children. Many of them have since been found accommodation in safer countries.

“They still send me photos,” the pastor’s wife tells me, pulling out her phone and scrolling through some of them with a smile. A mother grinning happily while hugging her young blond-haired daughter in Germany. A young family showing off their new temporary home in France.

Thank you messages left by refugees are written on one of the church walls. Credit: Kyiv Post.

As we leave, a volunteers is still cooking in the church’s quaint kitchen, stirring a wooden spoon in a large pot of soup bubbling away on the stove, getting ready for tomorrow.

As we head back to our own accommodation nearby, it’s hard not to feel humbled, guilty even. When heading off to Zaporizhzhia from Kyiv, I’d been feeling melancholy from the recent passing of my Nan back in England, along with being frustrated with the long power blackouts not letting me have a shower or get online. Seeing the resilience, the smiles on the faces of these strong and loving people, who are going through such oppressive hardships, makes me realize just how I’ve got nothing to moan about.

I think back to the stories my Nan used to tell me – the terrifying droning noise of the Nazi doodlebugs (V1 rockets) as they soared over her home in London, not knowing where they were about to land – her neighbor’s house, or perhaps hers.

In Ukraine, doodlebugs are now replaced by Kamikaze drones, their moped engines making a similar noise – a noise my Nan had never expected to return to Europe. The Nazi death squads going door to door in Poland have been replaced by Russian brutes going door to door in cities like Mariupol. Millions have been forced to flee on trains, just as Nan had been forced to flee to Ireland. History sadly repeats itself.

The Nazis are back in Europe – a different flag and emblem, but cut from the same cloth.

The following day, it’s reported that Huliaipole has been attacked by the Russians again, causing damage to another historical building. Even worse, in a village nearby, a 40-year-old woman was killed by Russian artillery.

Now, no longer moaning, I realize that the cliché frequently uttered to Western youth by those of my Nan’s generation couldn’t be more accurate.

“You don’t know you’re born.”

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter