The UK talks about those who died in World War I as being the “lost generation,” but the average age of those who died then was 24. The average age of Ukraine’s fighters today is 43, a different generation but one, perhaps, the nation can ill afford to lose.

Prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion, Ukraine planned to end conscription and a move to a professional, contracted armed force. This was enshrined in the policy paper “The New Concept of Military Personnel Policy - 2028.”

However, Russia’s full-scale invasion has raised the need to retain some form of conscription, at least in the short term, since professionalization had not really got underway. The Texty.org.ua data information site suggests that Ukraine currently has 1.1 million men and women in uniform, with potentially five million military-age citizens still living in Ukraine. It says that, according to the country's top military and political leadership, there is a need to mobilize an additional 500,000 to serve in the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU).

The Ukrainian military issues news site Militarnyi recently published an analysis article that compared the current discussions on the rights and wrongs of conscription into the AFU with the application of the draft in other Western European nations, such as Austria, Switzerland, Norway, Sweden and others. While a useful indication of how other states currently address their manpower requirements, none of those nations are at war.

EXPLAINER: Consular Service Suspension for Ukrainian Men Abroad – What We Know So Far

It is worth looking therefore at how those nations, who faced the same dilemma with which Kyiv is currently struggling, dealt with the issue when actually at war or when conflict seemed imminent.

United Kingdom

World War I

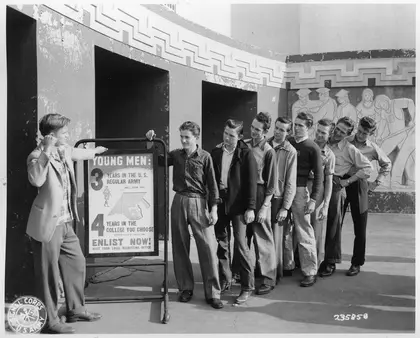

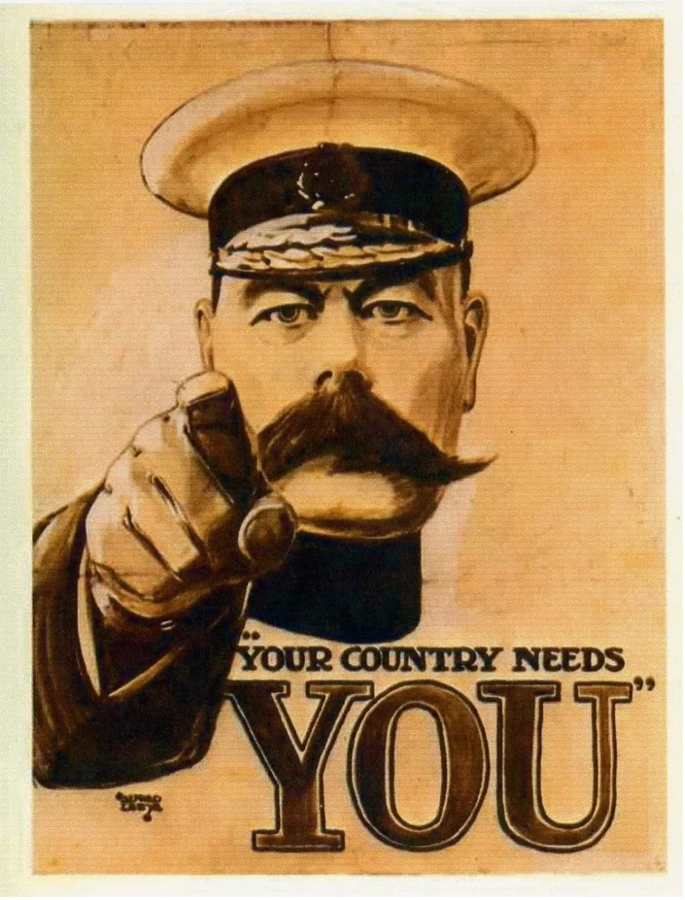

Prior to World War I, there had been no conscription in Britain with the reliance on a professional, volunteer army to secure the defense needs of the UK and its overseas empire. At the outbreak of the war, the manpower requirement was also initially met by volunteers.

By January 1916, the war had slipped into stalemate and losses could no longer be met solely by volunteers, so the UK government passed the Military Service Act. This legislated for single men aged 18 to 40 to be called up for military service, with exceptions on certain limited social grounds and for those involved in “work of national importance.” In mid-1916, liability for conscription was extended to include married men up to the age of 51.

Conscription lasted until mid-1919, with the last conscripts being released in 1920.

World War II

With the rise of Nazi Germany and subsequent international tension, the UK began a restricted form of conscription through the Military Training Act which required single men aged from 20 to 22 years old to undergo six months of basic training before being released into an active reserve.

At the outbreak of war, on Sept. 3, 1939, the National Service Act came into being. This imposed a liability to conscription for all men aged 18 to 41 which was extended in 1942 to all men aged between 18 and 51 and all females aged 20 to 30.

Statistics show that, overall, during the two wars, UK manpower requirements were roughly met by one third volunteers and two thirds’ conscripts.

Post 1945

Peacetime conscription under the National Service Act was modified in 1948 and required all men aged 17 to 21 years old to serve in the armed forces for 18 months, followed by a four-year reserve liability. With the start of the Korean War in 1950, the service period was extended to two years. National servicemen took part in all conflicts involving the British army until the system came to an end on Dec. 31, 1960. It was not until 2004 that the National Service Act was formally abolished.

Germany

World War I

Germany had embraced the concept of the “citizen soldier” from the 18th century onwards. Every able-bodied man, aged 17 - 45, was liable for military service. By 1914, it had a well-established and organized system of peacetime conscription. At the age of 20, men would undertake two or three years of peacetime training before being released but remained liable to be called up for service to the age of 45.

This meant that upon the outbreak of war, the German army expanded from its regular core of 800,000 to 3.5 million in just 12 days. In 1916, faced with the same manpower deficit as the UK (and France), the upper age for conscription was raised to 60.

World War II

After World War I, the Treaty of Versailles abolished conscription in Germany and reduced the authorized size of the German army to 100,000 volunteers.

On March 16, 1935, Adolf Hitler overrode this, making public his previously clandestine rearmament program. He declared the strength of the German army would be increased to 550,000 troops but, in fact, between 1935 and 1939 the strength of its armed forces rose to four million and to 9.2 million by 1944.

Post War Germany

The situation in Germany was complicated by the fact that it was split into two entities until reunification in 1990. The DDR, East Germany, roughly followed the Soviet conscript model (see below).

The conscript model used by West Germany and later the reunified Germany ran between 1957 until 2011. Undre the scheme men between the ages of 18 and 27 were obliged to serve either in the nation's military, the Bundeswehr, or perform an alternative service in civilian areas such as emergency management or medical care for a maximum of nine months.

General conscription was scrapped in 2011, with the goal to professionalize the troops and reduce the size of the Bundeswehr. Now, the German army consists only of career soldiers and long-term contract troopers, although Germany's Basic Law retains the premise that during emergency periods “men can be obliged to serve in the armed forces, in the Federal Border Guard or in a civil defense unit from the age of 18.”

Given that Germany’s armed forces have been unable to reach the planned full strength of around 200,000 by professional volunteers, coupled with concerns raised by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, discussions have restarted on the possible reintroduction of conscription as, for instance, Latvia has done since February 2022.

The United States

World War I

On May 18, 1917, Congress passed the Selective Service Act, which authorized the Federal Government to temporarily expand the military through conscription. The act eventually required all men between the ages of 21 to 45 to register for military service. Under the act, approximately 24 million men registered for the draft. Of the total number of US troops sent to Europe, 2.8 million men were draftees, and 2 million men had volunteered.

World War II

While not at war, the US was concerned by the progress of the Allies in the war against Germany in Europe and the Japanese in Asia. Isolationism, and the desire to “keep out of other people’s business” was strong, but with the fall of France, the government realized its army was unprepared to fight a modern war and surveys showed a growing majority in favor of conscription to prepare for the worst case.

On September 16, 1940, the US enacted the Selective Training and Service Act, which required all men between the ages of 21 and 45 to register for the draft. This was the first peacetime draft in US history. Selection to serve was undertaken by lottery, with those called up required to serve a minimum of one year in the armed forces. Once the US entered the war, the requirement to serve was extended to last for the duration of the fighting.

By the end of the war in 1945, 50 million men between 18 and 45 had registered for the draft and 10 million had been inducted into the military.

Vietnam war

Contrary to most people’s belief, around two thirds of those who served in Vietnam were volunteers, while the rest were selected for military service through the draft.

At the beginning of the war, the names of all US men aged 18 to 26 were registered in a revised version of the draft called the Selective Service System. As in World War II, individuals were selected to serve by means of a lottery and the draw was actually televised.

The main reason that the draft was so hated was how open to abuse it became.

In addition to deferment through college attendance or being employed in essential industries, those included in the draft were decided by local draft boards who were susceptible to outside political and social pressures. As a result, US forces largely consisted of those from poor working class and rural communities.

The Soviet Union

Conscription was used by the Soviet Union for the duration of its existence to bolster military function and operations. Conscription was introduced into what would become the Soviet Union in 1918, almost immediately after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 to strengthen the Red Army.

Conscription remained a constant presence in the Soviet state until its dissolution in 1991. Various policy amendments changed the size and nature of conscription intakes and the required length of service, with key changes to the policy occurring in 1918, 1938 and 1967.

Wartime conscription, specifically during World War II, saw a significant increase in the numbers drafted as well as a broadening of the pool of candidates available to be conscripted. Unlike countries such as the US that did not have a history of conscription, there was relatively little resistance to conscription policy among the population, which had been enshrined in the Soviet constitution. This said that military service was an obligation for all citizens, regardless of identity or status, and was seen as the national duty of all Soviet military-aged men.

World War II

The policy saw few changes until Sept. 1, 1939, when a new Law on Universal Military Service was enacted following the outbreak of World War II in Europe.

The new law saw large increases in service periods, ages of conscription and a restriction on reasons for exemption. The general period of service was increased from two to three years, and the conscription age was lowered from 19 to 17 for men.

Exemptions for those involved in higher education or for social reasons such as having several young children were abolished. The plan behind the increased conscription terms was to create two large groups of trained reserves, one for men up to 40 years of age, and the other for men up to 50 years of age.

In February 1942, Joseph Stalin issued an order to “conscript into the ranks of the Red Army… citizens in the liberated territories between the ages of 17 to 30.” This resulted in non-Russian inhabitants of liberated territory being forcibly conscripted into the Red Army as it advanced upon Germany, which has echoes of what has happened in the currently occupied areas of Ukraine.

Post 1945

A secret amendment to the law in 1950 increased the minimum term of active service by one year, to four – with no official decrees on the subject being issued in the Proceedings of the Supreme Soviet. The reason given for the secrecy was that it could suggest to the West that the Soviet Union was preparing for war. It was reduced to three years again in 1955, which coincided with the end of the Korean war. This suggests that the USSR had been preparing for the likelihood of it being dragged into the conflict.

The law was further amended in October 1967 to shorten service periods from three years to two, and the draft split into two separate call-ups each year, one in spring and the other in the autumn. This was due to the post-World War II “baby boom” which saw a large increase in young men reaching military age around this time. The change would allow a greater turnover of conscripts, allowing the size of the army to remain at levels the Soviet economy was able to sustain.

Russian Federation

The USSR’s two-year 1967 conscription term was retained after the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union until it was reduced to 18 months in 2007 and to one year in 2008. In 2021, all male citizens aged 18–27 were made subject to a potential one-year term of active military service with the number of conscripts for each twice-yearly recruitment campaigns being set by Presidential Decree.

In September 2022, following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russian President Vladimir Putin signed a decree for the “partial mobilization” of 300,000 conscripts in September. Despite claiming that the target had been exceeded, a second decree in November of that year allowed for those convicted of serious crimes, including drug trafficking and murder, to be mobilized into the Russian army. This suggests the target had not been met, largely because of the mass exodus from Russia of several hundred thousand military age men.

In July 2023, new legislation raised the maximum age for military conscription to 30 commencing from Jan. 1, 2024. It also banned men from leaving Russia from the day they are summoned to a conscription office. This may be indicative of the levels of casualties suffered by Russian forces as a result of the war in Ukraine.

Conscientious objectors

A conscientious objector is an individual who refuses to perform military service or any activity that supports military action because of religious, moral, freedom of conscience or other grounds. In some countries, conscientious objectors serve with the military as medics or stretcher bearers, while others are assigned to some form of social or communal service as a substitute for conscription.

May 15 is acknowledged by a number of organizations as International Conscientious Objection Day. While in history, many who refused to serve were punished, some even executed, it was acknowledged that in some religions such as the Quakers and Dutch Mennonites, an individual’s faith precluded them from fighting.

This right was enshrined in the UN’s 1948 “Universal Declaration of Human Rights,” which states that “everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion.” In 1974, the UN Assistant Secretary-General, Seán MacBride said: “In addition “to the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, one more might, with relevance, be added. It is ‘The Right to Refuse to Kill’.”

Conscription avoidance and evasion

It is important to make the distinction between a conscientious objector, sometimes called “conchies,” and conscription “avoiders” and “evaders.”

Draft avoidance is where the conscript uses the rules or, what some see as legal “loopholes,” to get out of having to serve to obtain a legally valid deferment to, or exemption from, conscription. This can include such things as: obtaining a student deferment if studying, having a genuine medical or psychological condition, being homosexual (in some countries), genuine economic hardship, holding an essential civilian occupation, and in some instances having several young children or disabled dependents.

Draft evaders or draft dodgers seek to dodge conscription in contravention of the law, which is generally considered to be a criminal offense. There are many ways that individuals try to evade their obligation to serve, the most obvious being simply to “run away,” a phenomenon with which Ukrainians have become all too familiar. There are also numerous other, less obvious, tactics that may not overtly break the law but usually involve false attempts to exploit one of the legitimate avoidance loopholes such as those mentioned above.

Draft evasion has been a significant factor in nations where conscription remains in force such as Colombia, Eritrea, Canada, France, Russia, South Korea, Syria, the US and now, Ukraine. Accounts by scholars and journalists, along with memoirs written by draft evaders, show that the motives and beliefs of those individual evaders may be complex – it is all too easy to simply put it down to cowardice, although in many instances that may be the main factor.

Concluding thoughts

Ideally, deciding on whether or not there should be conscription, is a political issue, rather than an expedient requirement as it was during past wars and in Ukraine’s current situation. For many nations, this may represent more than just filling military manpower requirements with other practical and symbolic purposes - many European right wing politicians see conscription as a way to "toughen up" its youth and undo the evils of drug abuse, the internet and rock music.

The debate on conscription should therefore also include consideration of elements beyond the short-term need. If it is imposed during wartime, consideration needs to be given to how long conscripts will be retained and the draft regime will last once hostilities end and whether sufficient volunteers can then be found to ensure a country’s post-war security can be assured. This is something that Ukraine may need to consider and address once the war against Russia is over.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter

Comments (2)

Ukraine has two problems - how to wage the current war and how then to maintain the peace because Russia is likely to remain a threat for the foreseeable future.

For the former, the UK model in WW2 worked pretty well and if you work in more women and the fact that people who may not fit the requirements of the front line can still contribute massively as drone operators and rear area support you have an extensive base to use.

The second might well be served by the Swiss model or Swedish and Finnish approaches that maintain a professional core and an extensive trained reserve.

Mr. Brown offers a timely and instructive report and analysis that should provide a basis for Ukraine's pending mobilization legislation. The one point that comes across is that there is no "one size fits all" solution, but decisions must be made regardless of the underlying "politics," and any decision is better than no decision.

It is hard to understand - given the dire situation in which Ukraine finds itself - why this process is taking so long for Ukraine to resolve. It is clear now (as Mr. Brown's report confirms) that reducing the draft age from 27 to 25 would be the mildest of all changes compared to that of other countries.

The March 31 deadline for a vote can not be allowed to slip. It is already past due because of the time-lapse from the day it is passed until new forces can be assembled, trained, equipped, and deployed. Until the EU (and, more importantly, Russia) sees this happening - in time for the expected increase in fighting later in spring and summer - it will be hard to impress Ukraine's supporters with the urgency of its needs.