Ukraine’s foot soldiers say they’ll fight Russian invaders in any case, but they would do it more effectively and fewer of them would die if they were equipped with modern combat optics, had more time to train to NATO standards, and were led by a professional corps of small unit combat leaders.

The Ukrainian army’s infantry has demonstrated that it can defend ground fiercely, but units might struggle when asked to perform more complicated missions like night reconnaissance, clearing a hostile village, or operating in cooperation with tanks or artillery, nine Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU) veterans ranked corporal to company commander told Kyiv Post in a series of November interviews.

Volodymyr Kadiev, 54, never planned to join the infantry. Before the war he ran a successful construction business in Hostomel, north of Kyiv. As a raw volunteer in a territorial defense battalion deployed in the path of the Kremlin’s assault on the capital, he found himself handed an AK-74 he had never fired and in charge of a defensive strongpoint overlooking a road intersection.

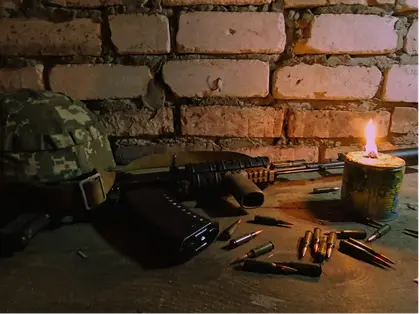

Kadiev and his mates had never trained together, had no communications gear save commercial mobile phones and had never been to a firing range. They learned how to operate a checkpoint from the internet. Relatives and neighbors brought them food. Their only optics was a pair of hunting binoculars.

Once the Russians retreated, in April, Kadiev set out to help his unit shoot straighter and see better in the dark. In a European country it would have been easy: the state would just buy rifle sights and night vision devices and hand them out.

EU Transfers €1.5 Bln Raised From Russian Assets for Ukraine

In wartime Ukraine, Kadiev said, it’s been more complicated. He had to contact a friend in the U.S., who knew someone in the military equipment trade, who found a Houston distributor called Primary Arms, then volunteers collected donations, money was transferred, and then Primary Arms received an order for several dozen units, and three months later a minority of Kadiev’s 300-man battalion unit had made in the U.S. gunsights on their rifles.

Soldiers at a firing range in Kyiv Region told Kyiv Post the American optics, with four-times magnification and a red dot target pip, are easy to use and ideal for split-second engagements. But until volunteers shake down friends and relatives for enough donations money to buy more, the battalion won’t get any more modern gunsights, Kadiev said.

“This is one item for one part of a single battalion. Ukraine has hundreds of thousands of soldiers fighting in the war,” he said. “Obviously, you can’t equip all those soldiers with volunteers and donations.”

Volodymyr Lysovsky, 31, ran a Harley-Davidson repair shop in the Kyiv bedroom community town of Bucha. He said he volunteered for local defense forces on the first day of the war, then transferred to a territorial defense battalion and later, promoted to sergeant, went east to fight with a special operations infantry outfit as a sniper. He fought mostly in urban battles in Severodonetsk and Lysychansk.

“When our infantry fights, it’s close in, 50-100 meters. Ninety-nine percent of the fighting is in villages. It’s all split second. Firefights come down to who reacts faster and more correctly,” Lysovsky said. ” You need the right tools, you need practice, and you need experience.”

Ukraine’s infantrymen would benefit greatly were they able replace the widespread AK-74 rifle of Soviet vintage with the American M4 carbine or German G36 assault rifle, because those weapons use high-quality NATO cartridges, while the AFU is supplied with sometimes iffy AK-74 rifle ammunition sourced from around the world, Lysovsky said.

“Captured Russian cartidges are very reliable, but some of the stuff from the Balkans and China, you can’t always depend on it,” he said.

Serhiy Hrach*, a regular army captain deployed in Kharkiv Region, in a November interview at a firing range told Kyiv Post that only a small percentage of Ukraine’s infantrymen probably meet NATO individual performance standards. Basic individual soldier field skills like marksmanship, ability to treat a bullet or shell splinter wound, or simply reporting accurately about something spotted on the battlefield are common shortfalls, he said.

“That sort of thing is systematically trained…and standardized in NATO units,” Hrach said. “But in our AFU that often depends on what a soldier happens to know and what personally feels like learning. Things are changing slowly but in our army right now training is bottom-up.”

“The Ukrainian army’s skills in combined arms maneuver are improving as they gain experience and as larger numbers of trained soldiers reach the front,” said Stephen Biddle, Professor of International and Public Affairs at School of International and Public Affairs, Columbia University. “(I)t would appear that their military proficiency has been growing over time.”

Hrach and others interviewed for this story singled out the AFU’s shortage of proper small unit leaders, specifically professional sergeants, as possibly the most critical gap in upping AFU soldier and combat unit capacity.

“In the AFU, soldiers follow not the rank but the most experienced guy. In NATO that leader is a sergeant, but we are at war and there’s no way our army can train enough sergeants properly. So we make do as best we can,” he said.

Sergeant Maksym Myronishchenko* serves in an air assault brigade currently deployed in Bakhmut sector, currently the scene of the most intense fighting along the entire 2,000 kilometer contact line. Myronishchenko in a telephone interview told Kyiv Post that an experienced sergeant is usually the difference between survival and becoming an early casualty for new soldiers. He said time in combat and rising gradually in the ranks is the best route to becoming an effective sergeant. Myronishchenko said he joined the AFU as a volunteer in 2014 shortly after Russia’s invasion of Donbas, became a professional soldier in 2016, and pinned on his sergeant’s stripes in 2019.

“But guys like me are few and far between, not everyone stays in the service, and not everyone survives”, he said. “Now we have a giant war, our army is going to the attack, our soldiers are going to have to learn on the job, we don’t have enough proper sergeants, and in war you pay for mistakes in blood.”

Myronishchenko and other AFU small unit leaders told Kyiv Post, without exception, that in their view as infantry soldiers, by far the most effective foreign assistance they have seen, more even than Western weapons, has been the basic military training for new Ukrainian recruits conducted by NATO instructors. Particularly-praised were training courses led primarily by British instructors in England. New Ukrainian troops are now arriving at combat units, he said, not just well-trained in weapons and basic infantry skills – but even more important, “they think like NATO soldiers,” he said.

*Interview subject requested a pseudonym be used for security reasons. He identified himself to a Kyiv Post reporter.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter