Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky and the evidence say much the same thing: the Russian Navy has been chased out the west end of the Black Sea and cargo ships loaded with Kyiv’s grain have been sailing smoothly through peaceful seas in the past two months.

The Ukrainian leader in a Tuesday statement at a Prague security conference said Russia’s once-dominant naval presence in the Black Sea was at an end and that “illusions are melting.”

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

“The Russian military fleet can no longer operate in the western part of the Black Sea and is gradually fleeing from Crimea. This is a historic achievement,” Zelensky said.

“The Russian leader (Vladimir Putin) was recently forced to announce the creation of a new Black Sea Fleet base… as far as possible from Ukrainian missiles and uncrewed surface vessels.

“But we will get them everywhere.”

Russia on Jul. 17 declared all Ukrainian sea ports under full blockade following the collapse of a multi-national agreement to move grain from both Russian and Ukrainian ports to international markets.

The Kremlin’s armed forces, primarily the men and warships of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet (BSF), could and if wished would halt any and all cargo ships moving in international waters to or from a Ukrainian port, and if military stores were aboard that ship would be confiscated or sunk.

The Kremlin declaration was intended to halt Ukrainian grain exports. It hasn’t worked.

Hungary to Block EU Funds For Member States Until Ukraine Allows Lukoil Transit

Kyiv on Aug. 8 challenged the Kremlin with an announcement of its own, informing shippers and sailors that the Ukrainian Navy would help implement “new temporary routes of civil vessels to/from Ukrainian Black Sea ports.”

The routes run along the Ukrainian coast in Ukrainian territorial waters and then pass through sea lines adjacent to the coasts of Romania, Bulgaria and Turkey, all NATO members.

Russian warships and mines still were a potential threat to cargo ships using the corridors, but Ukraine expects international maritime law to be respected by all, including Russia, the Kyiv statement said.

Unmentioned but broadly implied in the Ukrainian Navy statement was the international sea law principle that for a warring nation to enforce a blockade in international waters, its Navy must halt and board neutral ships heading to or from a port under blockade and inspect the cargo and determine its destination.

Attacking neutral cargo ships in international waters without making the check, by common international practice, usually constitutes piracy – and pirates, by those rules, are fair game to all navies.

Onn Aug. 13, the Russian Navy made a single attempt to enforce the blockade announced by the Kremlin, flying a Ka-29 maritime helicopter to a point in the western Black Sea, and landing armed boarders led by a lieutenant on the Sukru Okan, a Palau-flagged cargo ship en route to the Ukrainian port Izmail from Chalcis, Greece.

It was windy and the seas were rough and some of the Russian boarders appeared not overly experienced transferring from a hovering helicopter to the deck of a cargo ship, but somehow Russian boots needed to be aboard the Sukru so that the Russian Navy could enforce the blockade legally.

Failure to do so would have violated the free movement of civilian shipping in international waters – a trigger issue for many NATO states, particularly the US – which shifted frontline F-16 fighter jets to an air base in Romania last month, with the mission of strengthening NATO military capacity over the Black Sea.

Video made public by Kremlin-controlled media showed the Russian lieutenant berating, in limited English, the Surku’s captain for ignoring an order to stop. After a reportedly cursory check of cargo, the Russian boarders sent the Turkish-owned vessel on its way.

Since that mid-October high seas intercept, according to local news reports and regional analysts, the Russian Navy has made no substantial attempts to interfere with cargo ships heading to or from Ukrainian ports.

One possible reason for the gap between the Kremlin’s announced intent and Russian Navy action may be down to the Ukrainian Navy, which in reportedly four separate, nocturnal attacks from Jul. 24-Aug. 2 launched kamikaze sea drone attacks against the two Russian frigates operating in west Black Sea waters: the Sergei Kotov and Vasily Bykyov. Russian Navy spokesmen said Ukrainian robot boats all were blown up, but Ukrainian military information platforms claimed both frigates were hit, the Bykov fairly seriously.

On Sep. 13, a spectacular Ukrainian missile raid struck the Russian Black Sea Fleet’s home base in Sevastopol, a port on the western shore of the Kremlin-occupied Crimea peninsula. Three military dry docks were ruined, and a heavy amphibious assault ship and a modern attack submarine were destroyed.

A follow-up Sep. 22 missile wave hit BSF fleet headquarters during a senior staff meeting, killing or wounding dozens of Russian senior naval officers including, according to some news reports, the BSF vice fleet commander.

The weapon used in the strikes, the British Storm Shadow missiles, is precision-guided and a top-end NATO munition specifically designed to hit and sunk Russian warships at ranges out to 550 km. Ukraine’s domestically produced Neptune anti-ship missile reportedly reaches out to 300 km and on Apr. 3, 2022, sank the BSF flagship of the time, the cruiser Moscow. Kyiv has received US-made anti-ship Harpoon missiles from the US, Britain, Netherlands, Spain and Denmark, reportedly with a range of 200 km.

Those systems’ collective long-range reach into the western end of the Black Sea have long forced Russian warships to stay at least 150 km. from Ukraine’s coast and is more than sufficient to prevent the Russian Navy from interfering with a cargo ship corridor running along the west Black Sea coast, maritime security analysts have said.

The shipping market offers more proof of a near-abandonment by the Russia Navy of even a pretense of ability to back up a declared blockade of Ukrainian ports tied to the Black Sea with meaningful force. By early October, the top business news platform Bloomberg reported almost-daily ship arrivals at the ports Odesa and Chornmorsk.

The Ukrainian Black Sea News (BSN) platform, a long-established, Odesa-based publication providing shipping industry information since the early 1990s, in an Oct. 16 situation estimate reported that since Kyiv’s establishment of a corridor for cargo ships to move to and from Ukrainian ports skirting NATO territory, 31 ships made the trip carrying 1.3 million tons of cargo.

The market watch group BNE Intellinews on Oct. 25 reported that since Russia backed out of the grain shipping agreement and technically declared any cargo ship moving to or from a Ukrainian port a potential war target, “the Ukrainian grain corridor has seen the arrival of at least 42 ships in its ports, with at least 23 departing.”

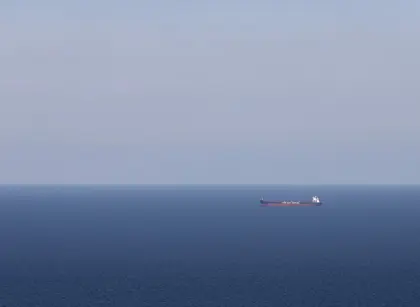

Navigation images published by BSN showed the Jolanda, a Liberia-flagged ship operated by the Hamburg-headquartered company Blumenthal JMK GMBH, heading north en route to the hub port Odesa, and passing through waters less than 40 km. from Moscow-controlled territory in Ukraine’s Kherson region – an almost point-blank range for Russian naval cannon and missiles. The BSN reported no incidents or outside interference met by the Jolanda or any other ship using the corridor.

Zelensky in his Tuesday statement vowed Ukraine’s Navy would keep on hunting Russian warships.

“We have not yet achieved full fire control over Crimea and the adjacent waters as of now, but it will happen. It’s just a matter of time,” Zelensky said.

The last reported location of the frigates Sergei Kotov and Vasily Bykov was tied up at a wharf on Oct. 15 in the Russian naval port Novorossysk, at the east end of the Black Sea.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter